HELENSBURGH and district has a long association with Youth Hostels and those who use them, but it is a much smaller number nowadays.

In its heyday, the Scottish Youth Hostels Association had at least 100 hostels open during the season, but today the association's website lists just 36 hostels available for the 2015 season — the nearest being Glasgow, Rowardennan and Crianlarich.

Helensburgh Heritage Trust director and local historian Alistair McIntyre used to be a hosteller, and has researched the subject.

Hiking in Britain and elsewhere in northern Europe, and the resultant demand for low cost accommodation, was a logical progression from the great outdoor movement which began to take hold in the late 1920's.

This was inspired by the Wandervogel Movement of the Weimar Republic in Germany, where the concept of the youth hostel was born.

The Scottish Youth Hostels Association was formed early in 1931, a year after the corresponding body for England and Wales.

Such was the enthusiasm of Sir Iain Colquhoun of Luss for the cause that as early as June 1931, meetings were taking place about building a hostel on his land at Inverbeg, with grant aid through the Carnegie Trust.

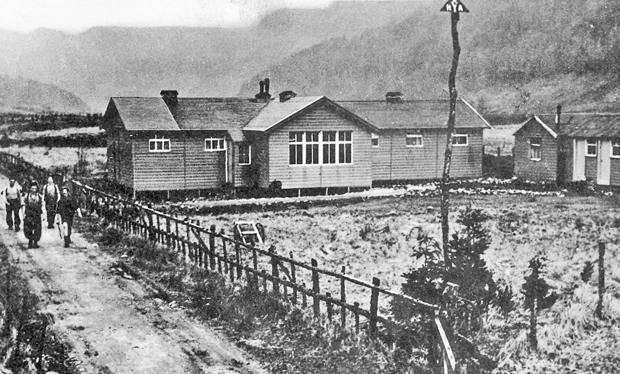

Work on the building was started weeks later, and the firm of Cowiesons completed a custom-built wooden building for 48 people in a mere ten days. Sir Iain performed the opening ceremony in August.

Inverbeg was among the first youth hostels in Scotland to open its doors — the first being Broadmeadows, a converted mansion in the Borders which had opened in May.

Despite its promising start, Inverbeg suffered an unexpected setback later that year when the warden was accused of embezzling over £7 of the takings. He was found guilty and was sentenced to nine months imprisonment with hard labour.

Because of its situation near Glasgow and beside Loch Lomond, Inverbeg quickly proved its worth, and an extension was added in 1934 to help meet demand.

Because of its situation near Glasgow and beside Loch Lomond, Inverbeg quickly proved its worth, and an extension was added in 1934 to help meet demand.

The association’s strategy was to establish a network of hostels so that it would be easy to reach the next one on foot or by bicycle, if not by public transport.

Soon Inverbeg formed part of a chain of easily-reached hostels including Glen Loin, near Arrochar, Crianlarich and Ledard at Loch Ard.

Ledard and several other hostels were reached by crossing Loch Lomond at Inverbeg, where the loch is relatively narrow — drovers had once swum cattle across there.

When the Inverbeg hostel was built, the traveller had the luxury of two ferries for the crossing. These were classed as ‘King's Ferries’, meaning that they had to run as advertised, during daylight hours, weather permitting, and could not charge in excess of the advertised rates.

The ferry based at Inverbeg was operated by rowing-boat, while the other, on the Rowardennan side, was worked by motor launch.

Each ferry could only take passengers from its own side of the loch, and any passengers who happened to be waiting at the jetty on the other side. Neither vessel was allowed to linger on the opposite shore in the hope that someone else turned up.

A complication was that if it was too rough for the rowing boat, there was no direct telephone connection between Inverbeg and Rowardennan to enquire about the motor launch. This had to be done from Luss or Tarbet.

Despite this, Inverbeg soon proved its worth, racking up some 2,635 bed nights in 1932, the first full season. There was also provision for camping beside the hostel, and old photographs show just how busy it could be at times with people in tents.

The smooth tenor of hostel life was interrupted early in 1940, when there was a near-fatal accident.

In the early years, even small hostels like Inverbeg were open all year, even in wartime. The warden, Donald McDonald, had been away, and on his return lit the fire in his house, which was close to the hostel.

The weather was very cold, and the pipes had frozen. There was a boiler at the back of the fireplace, and after a time, the heat from the fire caused it to burst in a huge explosion. The warden was severely injured, but survived.

Wardens came and went, some staying for one season only, others for a number of years.

By the early 1950's, the warden was Sidney Todd, popularly known as Sid, and it was during Sid's tenure that Alistair first came to learn about Inverbeg Hostel. There was an annual custom of treating children living in Glen Douglas to a Christmas party at Luss.

“Sid had a car, and had been prevailed upon to chauffeur some of the children to the party and back," he recalled. "I found myself amongst those in the car. I can remember little about events other than the benign appearance of Santa.

“As for Sid, I have only a vague recollection — he seemed a quiet man — but what I do recall clearly was his car, which was small and boxy, possibly an Austin.

“It was of course most generous of Sid to give freely of his time and transport, but on the return journey, it quickly became clear that a carload of youngsters was going to be too much for the car on the steep climb above Inverbeg.

“It was a case of getting out and walking up the hill — of course, for children, this merely added to the sense of adventure.

“I seem to remember Sid being called into action the following year, with the same result. In fairness to his little car, I recall a later occasion when a shooting-brake belonging to a local farmer also had problems on the hill.”

The warden who succeeded Sid was John Lamont, who served for seven years. Tragically, he was found hanged at the hostel in 1959.

Personal accounts of hostel life often make for absorbing reading, and one hosteller described an Inverbeg warden called Big Jim . . .

“He was a big bluff kind of guy, with a huge beard, and wearing an army sweater and a kilt. He claimed that the hostel was haunted, stalked by the ghosts of two previous wardens, one of whom had hanged himself from a beam.

“I was up early in the morning, and at that time, first up got the easiest chore from the warden. The layout of the hostel was like a two-level log cabin, with some stairs leading to the upper level, which served as a meeting-place for everyone.”

Inverbeg was a successful hostel, with up to almost 7,000 bed nights being recorded for some years in the 1950s and 60s. But from the 70s onwards, numbers gradually declined, and the hostel finally closed its doors in 1993.

Another early hostel in the area was Glen Loin at Arrochar, opened in 1932 on Forestry Commission land. It was the third custom-built hostel in Scotland, being built by the same firm which built Inverbeg, and on a similarly impressive time-frame.

Another early hostel in the area was Glen Loin at Arrochar, opened in 1932 on Forestry Commission land. It was the third custom-built hostel in Scotland, being built by the same firm which built Inverbeg, and on a similarly impressive time-frame.

The new hostel appears to have thrived from day one, and author Tom Hall, writing a year later, referred to it as “the famous Arrochar Youth Hostel . . . it was near this site that the Rucksack Club hut was erected, having the distinction of being the first youth hostel to open in Great Britain”.

The club hut appears to have been built in 1929 or 30, and may have been incorporated in the hostel building.

Hostelling in the Arrochar area was immortalised thanks to journalist and broadcaster Alastair Borthwick’s little 1939 book ‘Always a little further’, described by Alistair as a masterpiece which brilliantly captured the spirit of the 1930s..

The Glen Loin hostel, on Forestry Commission land near Arrochar, was the third custom-built hostel in Scotland, and opened in 1932.

Borthwick wrote: “On many weekends, I went to those youth hostels which lay within easy reach of Glasgow — I liked the people who lived in that world.

“It was a young world, governed by the young. The youth hostel movement is one of the most important social innovations of this century and there appeared to be no class of society to whom the appeal of the hostels did not extend.

“So to my mind it was, and still is, the greatest library of ideas and human experience in Scotland.

“I argued about the three-colour process in films with a cinema projector salesman in Glen Clova, was preached the Douglas Credit System by a budding chartered accountant at Inverbeg, and at Arrochar, early in the year, four German girls taught me the most exquisite folk songs I know.”

Borthwick explained explains that, on this occasion, Glen Loin had filled up with over sixty people seeking refuge from the rain.

Almost incidentally, someone playing a mouth organ had the effect of gradually causing everyone to join in what quickly became an evening of community singing and high emotion.

Borthwick commented that the Great Depression resulted in large numbers of unemployed people from the Central Belt swelling the ranks of those seeking outdoor recreation.

As a result, there were some who were unable to afford even the modest fees of the hostels — a shilling a night — although there were always some people who by choice refrained from spending money on transport and accommodation.

The ingenious strategies adopted by the thrifty or independent, to whom use of a hostel would have been anathema, in achieving their goals were hilariously portrayed by Borthwick.

For them — “haakers”, “minks” and “flatties” — the legendary Arrochar caves provided many with a free alternative to the Glen Loin hostel.

A second Arrochar hostel opened in several years later at Ardgartan, and while there were some fears of competition with Glen Loin, both hostels thrived. Eventually, though, Glen Loin closed in 1950.

A second Arrochar hostel opened in several years later at Ardgartan, and while there were some fears of competition with Glen Loin, both hostels thrived. Eventually, though, Glen Loin closed in 1950.

Ardgartan, a converted mansion, was opened in 1936 by Sir John Stirling-Maxwell, who was a major figure in the society of his day.

A landowner like Sir Iain Colquhoun, who was present at the event, Sir John, the honorary president of the Scottish Youth Hostels Association, was similarly prepared to put his money where his mouth was, hosting a spectacularly-located hostel on his remote Corrour estate, known as Loch Ossian Hostel.

Ardgartan was taken over by the military in the Second World War, but afterwards resumed its former role. Closed in 1968, the building was replaced the following year by a custom-built hostel on a nearby site opened by Prince Charles.

As with many other hostels, use of Ardgartan declined from the 1980s onwards, and it closed down in 2001. It has been replaced by a large hotel run by the Lochs and Glens holiday chain.

Despite Helensburgh’s location and excellent transport links, the town never featured a youth hostel. The nearest was the Rahane Youth Hostel on the Rosneath Peninsula, the 35th hostel to open in Scotland.

A farmhouse conversion, high on the hillside, it was opened in July 1933 by Otto Shlepp, Emeritus Professor of German at Edinburgh University and a founder-member of the SYHA.

Offering accommodation for twenty people in five dormitories, and equipped with showers, it was strategically placed because as well as forming an ideal jumping-off point for Helensburgh, and being within easy reach of Inverbeg and Glen Loin, plans were afoot to open hostels on the Cowal Peninsula.

Rahane would have played a pivotal role in linking the different areas. Sadly, for a reason unknown, the hostel was forced to close suddenly on May 25 1934, never to re-open.

It could hardly have been through lack of use, because for the short part of the season it was open, some 729 bed nights were recorded.

Another hostel did open on the peninsula — Cove Castle Youth Hostel.

Built in the Scots Baronial style, and dating from 1867, this fairy-tale building had as its most famous resident the brilliant but eccentric chemist and industrialist James Ballantyne Hannay.

His claim to fame rests on his experiments to manufacture diamonds, and experts have puzzled for years over the validity or otherwise of the results.

James and his wife Caroline had three children, and ownership of the Castle, which had been in the family’s possession since the 1880s, was ultimately vested in two unmarried daughters.

In 1942, the building was made over to the SYHA, and the surviving daughter, Eva, moved to a flat in Glasgow.

Cove could have helped link the Cowal hostels to the Loch Lomond group, but there was the complication of no direct transport between the Rosneath Peninsula and Cowal, and so Cove may have been perceived by hostellers as being relatively isolated.

Again, the internal lay-out of the building may have posed challenges for use as a hostel, or there may have been maintenance overheads. Wartime conditions may not have helped.

One account states simply that the building proved unsuitable as a hostel. So it ceased in that role in 1948, and returned to use as a private residence.

An even bigger building, Auchendennan on the banks of Loch Lomond between Arden and Balloch, which was built for a Glasgow merchant, was made over to the SYHA in 1945.

An even bigger building, Auchendennan on the banks of Loch Lomond between Arden and Balloch, which was built for a Glasgow merchant, was made over to the SYHA in 1945.

Not only did the massive size of the new acquisition pose a big challenge, it had also been occupied by the military during the Second World War and remedial work was required.

Financial aid was found and SYHA volunteers rallied behind the project, and it opened for business in 1946.

Author Maurice Lindsay described it as “the biggest hostel in the World”, while the editor of the Third Statistical Account of Scotland called it “the biggest youth hostel in Scotland”.

It had additional roles as a conference centre and venue for Glasgow University ‘Fresher Camps’, and the bed-nights statistics were most impressive.

In 1954, there were 22,576, while in 1972 there were 18,907. A popular early Helensburgh Advertiser columnist, Betty Wood, whose husband Jim was a leading figure in the SYHA, lived in the large and imposing mansion.

Eventually, however, times caught up with even this jewel in the crown, and the hostel closed in 2012 and reverted to private ownership, as have many others.

Times have changed, and today the SYHA website listed only 36 hostels available for the 2015 season compared with over 100 at its peak.

Alistair, who often used hostels from the late 1960s until about 2000, staying in over 560 different hostels, still sees a role for them.

He believes that no-one can fault the Association for not changing with the times, and today there is much more family-friendly provision than before.

“Fellow-hostellers I have come across have almost invariably been fine people, with a real love of the countryside, and with their own stories to tell,” he said.

“In the summer months, many of the younger hostellers are from overseas, mostly students, and invariably they have an impressive command of English.

“Without exception, I have found the hostels to be welcoming and pleasant places in which to stay.

“Long may the youth hostel system continue, is my heartfelt plea. It would be a real tragedy if this precious national institution were ever to cease to function.”