A BOOK which gives one man’s fascinating memories of Garelochhead was published late in 2017.

Entitled “Recollections of Garelochhead 100 Years Ago”, it is based on the memoirs of William Hamilton, who was born in the village in 1889, edited by his nephew Graham.

Written late in the author’s life, it records in marvellous detail and clarity his childhood and youth before the First World War.

Although the focus is on Garelochhead and district, it almost certainly replicates the kind of existence lived by countless rural communities at that period.

The family livelihood was built on a local joinery business, started by William’s grandfather, who had come to Garelochhead from Ayrshire in the 1830s.

This was just when land for housebuilding was being feued, with consequent demand for precisely the sort of skills he had to offer.

William Hamilton, who was in his eighties, wrote in a terse and direct style, and readers are drawn seamlessly into domestic life, with the author being brought up essentially as part of an extended family.

As well as his father, several other family members worked in the joinery business, while two aunts ran a drapery shop in the village.

A sense is gained of a society more laid-back, and with closer ties to the land, than is generally the case today.

For example, one of the aunts who kept the shop also had a milking cow, which was always with calf in the spring. The byre was just across the road from the house.

A short distance along the road lived the blacksmith, Sandy Gilmour, who had several cows of his own.

Each morning, the various cows would meet up, and make their own way up the road towards Whistlefield for the day’s grazing, and would usually be trusted to return of their own accord in late afternoon.

Both families also kept poultry, which were free range in the widest sense.

Such a seemingly relaxed regime would be almost impossible to imagine today, but it would be quite wrong to look upon the village as a rural idyll.

Any thought of a so-called ‘Golden Age’ is probably little more than wishful thinking. The writer also refers to the long working hours — shops seldom closed before 11pm on Saturdays.

Another example of the sorts of challenges people faced in those days was an outbreak of scarlet fever which raged through school.

Medical care was then relatively rudimentary, and at that time, the disease was rightly one to be feared, and several of William’s siblings ended up in Helensburgh Fever Hospital.

The book is by no means all negative, and much of the text looks at life through the eager excitement of youth, though there are a number of mature reflections by the author.

William’s first teacher at Garelochhead School was Miss Wood, whom he called “a big kindly woman”. After several years, he transferred to the headmaster’s class.

William’s first teacher at Garelochhead School was Miss Wood, whom he called “a big kindly woman”. After several years, he transferred to the headmaster’s class.

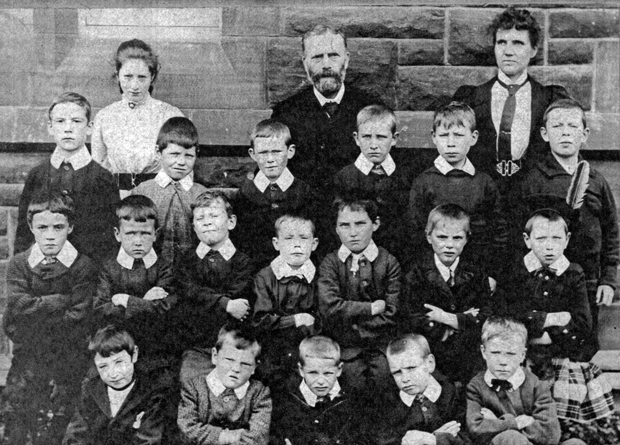

Headmaster from 1874-1910 was John Connor, and he was assisted by his eldest daughter Nan, who is referred to as a pupil teacher. He is pictured left with pupils, c.1898. To the left is Nan, his eldest daughter, described by William as a 'pupil teacher', while to the right is Miss Wood, described by him as 'a big, kindly woman'.

Several pupils have been identified, including Dan Wilson, extreme left, front row. The photo was kindly donated by Dan's daughter, Anne, who still lives in the village. Another pupil who has been identified is George Gall, third from left in the back row of boys.

William’s description of Mr Connor reads: “He was of medium height and stocky, with a brown beard and bushy eyebrows.

“He had pale blue eyes which often showed a humorous glint, and possessed the steadfast gaze of one whose life is spent in the observation of human nature.

“He was one of the old-time dominies, now alas long extinct. His pupils could never make the excuse they had learned little from him.”

There were many well-known personalities of the day. One was Susie Reid or McGlone of “Susie’s Castle” fame, and he wrote of her: “Susie knew everybody and everybody knew Susie. She talked to anybody and everybody.”

Then there was “King Duncan” McKichan, piermaster at Mambeg for 50 years. Duncan, like many others, also kept livestock, and like many of the McKichan family, did a good deal of fishing too.

Other characters included Sandy Gilmour, the brawny village blacksmith, a man of many talents — but few words.

Geordie McKinlay was the roadman, whose ‘beat’ was from Balernock to Witches Bridge, on the Finnart road.

Always cheerful, no matter the weather, he toiled ceaselessly to keep the road in good condition.

“Old Greenfield” and “Faslane” were both McFarlanes, but always known by the names of their farms.

Their very large holdings extended as far as Garelochhead, and both were good friends to the village.

Then there were the Irish labourers, men who had worked on the construction of the railway, but a number of whom had stayed on to help maintain the track.

They are described as fine, upstanding men, with a simple but wholesome diet, and who were never seen to be the worse for drink — nothing at all like the stereotype image of the drunken and feckless navvy.

These and others are brought to life by William’s pen.

At that time there were also a number of very wealthy people living in the district, and there are fascinating glimpses of their character and lifestyles.

Miss McDonald (pictured right), whose family owned the Stewart and McDonald department store in Glasgow, lived at Belmore, now inside the Faslane base.

Miss McDonald (pictured right), whose family owned the Stewart and McDonald department store in Glasgow, lived at Belmore, now inside the Faslane base.

She had her own steam yacht, complete with crew, mostly from the West Highlands, fitted out in smart blue uniforms.

William writes that she supported all good causes, and helped provide work for unemployed local people.

Also well-known were the Brooman-Whites from Arddarroch, whose family business originated in the huge chemical works at Shawfield, near Rutherglen. Richard Brooman-White was the first person in the district to own a motor-car, and tackled the challenges faced by the motoring pioneers.

Colonel and Mrs Marryat lived at Finnart House. Mrs Marryat was a Caird, whose wealth was derived from the jute mills of Dundee. The Colonel was related to Captain Marryat, author of rollicking sea-stories such as “Mr Midshipman Easy”.

William had a good deal to say about the Brownes of Bendarroch, the “big hoose” in the village proper.

Family finances were based on marine underwriting, but one single disastrous business decision cost them dear, and it was only thanks to the private means of Mrs Browne that the family managed to remain afloat.

William thought very highly of them, and he wrote: “The Brownes of Bendarroch were one of those families who lived to help other people, and the good work they did for our village can never be properly estimated.”

William loved to explore the surrounding area, and this led to various adventures. One of the most notable was a night-time fishing expedition to Loch Goil, led by a great pal, Peter McKichan.

By the time of this escapade, Peter had married, and was living over the hill at Portincaple.

When they arrived back in the “wee sma’ hours” William was absolutely exhausted and starving. He refers to the meal set down to him by Peter’s wife on their return as simply the best he ever enjoyed.

William’s great love was natural history, and he writes about the animals, birds and plants which flourished then. Many species have now vanished, or are but a shadow of their former selves.

William was very keen on fishing too, and it is a similar story of decline. The sea lochs in his day contained good stocks of fish including cod, haddock, whiting, plaice, hake, saithe and coalfish. Sea trout fishing was excellent.

In his day, the glory years of herring fishing had long gone, but even so, good catches could still be landed from time to time.

These and similar passages beg the question, perhaps politically incorrect to ask — granted that there has been so much change in the name of ‘progress’, what has been the true cost in environmental terms, and has it been worth it?

William’s account is not parochial, and it is fascinating to learn about how some national and even international events impinged upon the local community.

He describes the celebrations to mark Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, and the Coronation of King Edward V11.

Readers can scan the Royal Train (pictured above) for sight of His Majesty; and enter the pierhead office of ‘King Duncan’ at Mambeg, where the walls are full of pictures of the Boer War, and all the talk is of that conflict.

Although working life must have been tough for most in William’s youth, he refers to an even more demanding era long before his time.

For instance, he could only remember his paternal grandmother as being very old and frail, but how different it had been in her youth! Born in 1808, her weekly task as a young woman was to take farm produce to Helensburgh market on a Friday.

This might sound simple, but she had to travel from her home at Cuilimuich farm, which lies by the banks of Loch Goil, some way north of Carrick Castle.

This meant a very early rise, then she would load baskets of eggs, butter and other produce on to a small boat. She would row across to Portincaple, where the boat was beached.

The baskets were carried over the hill to Garelochhead, where a horse and cart would be waiting. There, she and others on a similar mission would load their goods on the cart, and walk behind it to Helensburgh where she would set up stall and go about the task of selling her produce.

Her route took her back the same way, but this time she brought commodities such as sugar and tea for home consumption.

Quite apart from the physical demands of such a journey, there was also the factor of bad weather to be taken into account, and sometimes she would be stormbound.

On one occasion, when thick mist rolled in, she was forced to spend the night crouched under a large boulder.

There are certainly young women today physically capable of such a regime — but they would nowadays probably be ranked as elite athletes.

One silver lining was that her route took her past the joiner’s shop where William’s grandfather was working, and this enabled romance to flourish.

William’s world was one in which there was no radio, TV or smartphone, but people made their own entertainment, whether it be sports, games, or cultural pursuits.

The book gives a sense of a community drawn together through such activities, with the consequent fostering of a community spirit.

One popular pastime was beekeeping, and indeed this was to have a seminal influence on William’s life as the art and science of beekeeping was to form the basis of his livelihood.

The Hamiltons had long kept bees before the author’s time, and the discovery of some beehives used by a late uncle was something of a eureka moment, although friends and neighbours like Sandy Gilmour and Peter McKichan, also keen beekeepers, may well have provided encouragement.

The book has a fair amount of coverage of this time-honoured occupation, and William has the knack of providing a most interesting narrative, while never getting bogged down in technical detail.

The book might never have been published had it not been for the beekeeping factor. But overall, it is a model of local history at its best, and should prove a most valuable addition to bookshelves.

The publisher too has done a very fine job to match the quality of the contents. The illustrated front cover, the quality of paper, the choice of typeface, the print size, and the general ‘feel’ are all excellent.

There is no index, but there are twenty chapter headings which themselves are fairly explanatory.

When one looks back in the fullness of time, there is possibly a natural tendency to remember the good times rather than the not-so-good. Does that apply here?

Inevitably, in a book like this, the reader may reflect upon the vast changes that have taken place between then and now. A litmus test might be — are we any happier today than we once were? The only one way to find out is to read the book!

The story of how the book came to be published is interesting, as it is not clear whether William ever meant to bring his account to a wider audience, or whether he intended it for family eyes only.

After his death, a niece, Evanda Hamilton, to her everlasting credit, realised the merit of the script, bound up a typed copy along with a number of illustrations and brief preface, and placed copies in local libraries under the title “Memories of a Country Boy”.

In the early 1990s, the late Tom Gallacher, ex-Denny’s Shipyard draughtsman turned journalist and playwright, presented an overview of the manuscript in the Helensburgh Advertiser, along with a heartfelt plea for it to be published.

That call has now been answered by Graham Hamilton, himself a keen beekeeper.

Graham, whose career has been based on forestry management, has edited the original text and provided some footnotes, but has consciously sought to keep as faithfully to the original text as possible.

The beekeeping factor has yet another part to play in the story, as Mike Thornley (left), proprietor of Glenarn Gardens at Rhu and a dedicated keeper of bees, played a vital role as catalyst and go-between in the chain reaction that led to publication.

The beekeeping factor has yet another part to play in the story, as Mike Thornley (left), proprietor of Glenarn Gardens at Rhu and a dedicated keeper of bees, played a vital role as catalyst and go-between in the chain reaction that led to publication.

Mike has written at least once before about William in beekeeping journals. So, given all this background, it is entirely appropriate that the new book has been published by Northern Bee Books.

William’s later life is not fully covered in the book, but it does mention his time with the old Volunteer Movement — he was attached to the Helensburgh-based ‘A’ Company of the Dunbartonshire Volunteers. The Volunteers evolved into the Territorials, and the 9th Argylls.

With this background, William would have been almost pre-destined to serve in the First World War. At some stage, he transferred to the Royal Flying Corps, and mercifully he survived the terrible carnage.

Resuming civilian life, William took up a lecturing post at the West of Scotland Agricultural College, where his main subject was beekeeping.

In due course he became a lecturer in beekeeping at the University of Leeds, followed by a similar post at the Yorkshire Institute of Agriculture, where he remained until his retirement in the 1950s.

He became a recognised authority on beekeeping, and it was a natural progression for him to write a book on the subject.

Entitled “The Art of Beekeeping”, this was first published in 1945, and became a best-seller and textbook for many years. I am told that there are active plans to have it republished.

In private life, William married Evelyn Margaret Crawford, then living in Garelochhead, in 1921. Their only child, Evelyn, was born the year after. Sadly, both predeceased him.

After retirement in 1955, he spent some time in Canada, where quite a few family members were already living, and of course were, and are, keeping bees — one relative has 5,000 hives!

William returned to Scotland, settling first at Garelochhead, and later at Blairmore, Dunoon, where he died in 1977 at the age of 88.

The 126-page paperback is published by Northern Bee Books of Hebden Bridge at £11.95, and is available to purchase online.