TRAINING SHIPS were a way of life — and a hard one — in the Gareloch from 1869 for 54 years.

But Helensburgh and Rhu benefitted in various ways from the two former sailing ships moored off Kidston Point and the boys who lived on them.

An account of life aboard first appeared in the March 2010 edition of the newsletter of the Glasgow and West of Scotland Family History Society, and was written by one of its members, William B.Black.

Editor Sheila Duffy has kindly given permission Helensburgh Heritage Trust to republish his article here . . .

With the massive expansion of Glasgow in the early 19th century poverty and social deprivation reached horrific levels — in particular the numbers of children living on the streets with no obvious means of support.

Among the more prosperous citizens some considered that it was their moral duty to try to make these children "respectable members of the community." This led to the founding of an industrial school in 1847, a day school only up until 1854, then came the Industrial Schools Act in 1866, defining precisely the children to be included and also introducing a licensing system.

Ten years earlier the Royal Navy had introduced training ships to prepare boys for entry into the Service and, following the new Act, Lord Shaftesbury decided that this concept had merit for the Merchant Navy, opening the first civilian training ship Chichester in December 1866.

Others followed and on November 5 1868, John Burns, senior partner in Cunard, hosted a meeting in the Royal Exchange, Glasgow with a similar objective.

This agreed to the foundation of the Clyde Industrial Training Ship Association, with Burns as president and the local MP, Robert Dalglish, was asked to approach the Admiralty for provision of a suitable vessel.

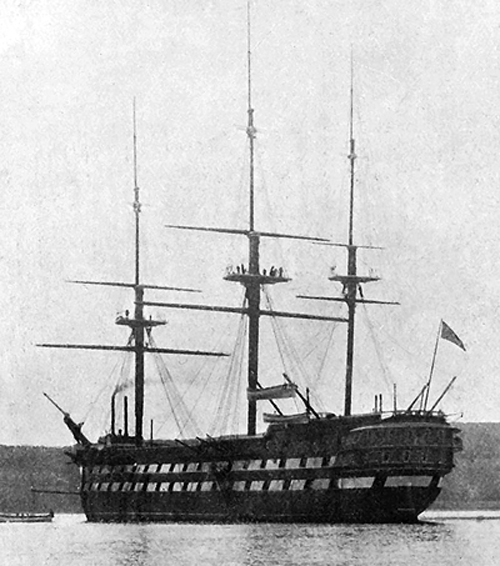

The vessel selected was the obsolete wooden sailing warship Cumberland, which arrived on the Clyde in May 1869.

By September she had been refitted and was berthed midway between Rosneath and Rhu, with a row of houses in Rhu — Cumberland Terrace (right) — being provided for the use of families of staff.

By September she had been refitted and was berthed midway between Rosneath and Rhu, with a row of houses in Rhu — Cumberland Terrace (right) — being provided for the use of families of staff.

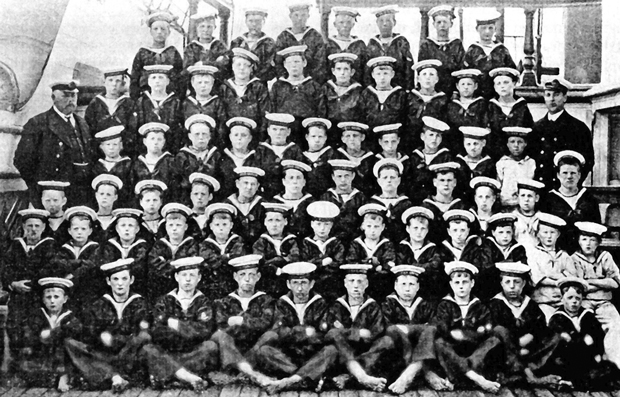

The age range of boys was from eleven to fourteen and, when the ship opened there were 176 aboard of a capacity for 360, sleeping in the lower deck in iron framed beds.

Day started at 0530, 0600 in winter and was broken down in to a mixture of school and practical classes. As well as seamanship, boys received instruction in tailoring, shoemaking, bookbinding and brush making, while working with the cook taught basic culinary skills.

Their work day ended at 1630 and, after supper at 1700, they had some recreation time until pipe down at 2130.

As the ship settled into this routine time was allocated within the working day for tuition on reed or brass instruments or, alternately choral singing.

There was no instructional programme on Saturday, the entire company being involved during the morning in Captain's Rounds, followed by ‘Clean Ship’. Then in the afternoon they were taken ashore to play football in a field above Rhu.

After two months aboard, subject to good behaviour, boys were permitted a monthly visitor, either friend or family.

Parcels were permitted to be brought but were subject to search when they came aboard. Despite the age of the boys this proved essential as, frequently, they included tobacco, which was confiscated.

The ship was non-denominational and on Sundays the Captain would hold a religious service, although it is not known if special arrangements were made for Roman Catholic boys.

Soon after Cumberland opened, a small cutter, Racer, was obtained, both to act as an isolation hospital for infectious diseases and provide suitable sailing experience for the boys in the summer.

Another recreational facility was a run ashore at Rosneath and this led to a Royal connection lasting many years.

Princess Louise, daughter of Queen Victoria, married the Marquis of Lome in 1871 and from that date was a regular visitor and benefactor to the ship.

With strong local shipping connections, recruitment of leavers into the merchant marine proved steady, with several achieving the rank of master mariner in later years.

Little progress was achieved in this direction with the Royal Navy, despite changes being made to the syllabus several times at their suggestion. This included in 1880 the purchase of the brig Cumbria, permitting older boys to carry out extended cruises as far as the English Channel.

Another was the introduction of arms drill, using Schneider rifles and cutlasses. Most boys were of small stature, so the handling of these heavy weapons proved a sore trial to many over the years.

A further innovation arose from gas being introduced into the ship in 1873, an engineer being employed, who also gave the boys instruction in tinsmith skills.

The Captains of the ship had all been ex-Royal Navy, and the third to arrive in 1887, Commander George Thomas Deverell (left), became a legend.

The Captains of the ship had all been ex-Royal Navy, and the third to arrive in 1887, Commander George Thomas Deverell (left), became a legend.

A strict disciplinarian, his service had been in small ships and he took a personal pride in building positive relationships with the boys.

Even after boys left he kept up a regular correspondence with many and took great pride in their achievements, relaying them eagerly to the yearly General Meeting.

He remained in command until 1912 and, when World War One broke out, he returned for six months when his replacement was recalled to the Service.

This remarkable service almost faltered within eighteen months of Deverell joining the ship, ironically, due to the actions of disgruntled boys.

During Saturday February 16 1889 there had been a brief scuffle among some boys and, when Deverell could not identify the culprits, he put their entire mess on ‘bread and water’.

The mess complained and Deverell suspended the punishment the next day, but it appears that resentment continued throughout the day.

Around 2.34 George Maddick, the ship's carpenter, who was officer of the watch, was doing his rounds, when he smelled smoke.

Mainly This was coming from a clothing store in the orlop deck, the lowest one in the ship, and when the hatch was opened, dense smoke billowed out.

The fire alarm was sounded and Deverell hurried out from his cabin aft, unfortunately locking the door with his Newfoundland dog still inside.

Boys manning the fire pumps attempted to contain the blaze but the thick smoke drove them back and, realising that the fire was out of control, Deverell ordered “abandon ship”.

All of the boys and staff aboard, plus Deverell's family, evacuated safely, although the dog was forgotten and became the only casualty.

The boys were taken initially to Cumbria then on the following day to Rhu School, then to the former House of Refuge in Glasgow.

Investigations soon concentrated on four boys, one of whom had absconded recently, but although one eventually confessed to a minor role, none of the main participants did so.

They stood trial for arson on April 15 1889 but the evidence proved flimsy and one was acquitted, while the others were found Not Proven.

Cumberland had burned to the waterline, being broken up on Rosneath beach, and it was not until November 1891 that the boys were able to leave the old House of Refuge and return to a new ship.

She was another wooden warship ( ), originally named Revenge but, unlike her predecessor, she had steam propulsion. This was removed for her new role, while her name was altered to Empress an indirect appreciation of the interest of Princess Louise.

), originally named Revenge but, unlike her predecessor, she had steam propulsion. This was removed for her new role, while her name was altered to Empress an indirect appreciation of the interest of Princess Louise.

The regular routine was resumed with one addition, gymnastics, a fully equipped gymnasium being fitted within the ship.

This did not preclude games ashore, although a new field had to be obtained, immediately to the east of the Ardencaple Inn.

It was nearly two years after the Cumberland blaze that the boys were able to leave the old House of Refuge in Glasgow and return to the new ship.

She was another wooden warship, originally named Revenge but, unlike her predecessor, she had steam propulsion — although this was removed for her new role.

A further innovation around this time was the provision of a hostel at North Montrose Street, Glasgow, for use by former boys without a permanent home and as a short term for current ones when necessary.

Supervising it was an inspector, whose role also included monitoring regularly the boys who had been discharged back to their homes. On at least one occasion this resulted in a lad being returned to the ship, having been exposed to serious physical abuse by his father.

With the 1872 Education Act had come an improvement in standards within the ship and an extension of the curriculum.

This included technical subjects, whose examinations were supervised by what would later become the Science Museum in London, until taken over by the Scottish education department in 1897.

By this time navigation, nautical astronomy and drawing also had joined the syllabus, further enhancing the prospects of those wishing a career at sea. 1899 also saw the demise of the brig Cumbria, now in poor repair, used for older boys to take cruises, and she was replaced by the yacht Selene, formerly owned by the Clyde Sail Training Association chairman, Thomas Henderson.

The steady improvement in education received a severe setback by 1905, with a decline in the previous four years leading to the resignation of the headmaster, H.M.Ferguson.

Commander George Thomas Deverell considered that he and his staff had made little effort to communicate effectively with the boys and, therefore, chose to replace most of them.

Apart from the Cumberland arson attack, crime appears to have been mainly of a minor nature. In such an enclosed community outbreaks of bullying were inevitable, but the staff were prompt in eradicating it.

During Deverell's command only thirteen boys had to be transferred to shore reformatories, an excellent record given the number of boys aboard each year. As an incentive to good behavior, Deverell introduced a system of Good Conduct badges.

Award of these also included additional payments of up to 6d per month and additional leave, while outstanding boys were promoted to petty officer, receiving an additional 2/6d per month.

Even after leaving, those who joined the merchant marine continued to receive encouragement. Completion of an initial voyage with a ‘Very Good’ discharge in their pay book would result in payments of up to 10/-, dependent upon its duration.

Annual home leave totalled 33 hours per boy, and in 1909 533 instances were granted with no boys reported as overstaying.

Annual home leave totalled 33 hours per boy, and in 1909 533 instances were granted with no boys reported as overstaying.

Always aware of the potential effect of infectious disease aboard, when epidemics arose in Glasgow leave would be curtailed, although this was very rare.

All boys were examined medically on a regular basis but it was not until 1905 that a dentist was added to this routine. That year also saw the introduction of a first aid class, followed by one covering all aspects of signalling.

The reed and brass bands flourished throughout the life of both ships, a bandstand being built by the Kidston family of Helensburgh at Craigdhu (now Kidston) Point, where they performed regularly.

This was joined in 1894 by a pipe band and, for the remainder of the existence of the ship all played regularly ashore around the West of Scotland.

1899 saw the introduction of the Industrial Schools Football Cup and every year one of the ship's teams either won it or were in fierce contention up until the last stages.

All boys were encouraged to learn to swim, several being awarded Royal Humane Society certificates for rescues of persons in trouble in the vicinity of Empress.

When an Industrial Schools Swimming Trophy was introduced, again the ship produced a team to compete. Unfortunately they were unable to emulate the footballers — Deverell attributing this to the lack of a proper swimming pool in which to train.

By 1913 Deverell had served 29 years in command and, despite pleas to remain, retired in that year. Outbreak of war in 1914 saw his brief return when his successor was required to return to active service.

During hostilities 1,475 former boys served, either in the armed forces or Merchant Navy, of whom 75 were killed and 14 commissioned as officers. During the war the financial situation of the Association began to decline, just at a time when Empress herself was beginning to show her age.

By 1915 a deficit of £1,676 had accumulated, partly because of £1,892 having to be spent in repairs.

As early as 1885 HM Schools Inspector had sought a shore-based hospital, an arrangement with Helensburgh being deemed acceptable. By 1916 this was no longer so, and in the following year Woodside House in Rhu was leased.

With this came the first female member of staff, the matron, Miss Christie, who remained until her marriage in 1920.

That year also saw Rosneath Castle-based regular visitor and benefactor Princess Louise, daughter of Queen Victoria, dedicate a war memorial for the former boys lost during the conflict, although it did not list individual names.

Despite the introduction of radio training the education syllabus altered little and the number of boys being referred by local authorities declined steadily. By the end of 1922 only 140 remained and early in 1923 increasing costs led to the decision to close the ship. This took place on 30th June 1923 at the end of the current school term, by which time it was calculated 5,629 boys had passed through both vessels since inception.

Of these 3,380 had joined the Merchant Navy and there had been 58 deaths, 12 from tuberculosis which was a regular killer at that time.

Empress was towed away to Appledore, Devon, for breaking up on March 20 1924, large crowds lining the shore at Helensburgh and Rhu to bid her farewell, doubtless including a sizeable number of her former boys and their families.

Empress was towed away to Appledore, Devon, for breaking up on March 20 1924, large crowds lining the shore at Helensburgh and Rhu to bid her farewell, doubtless including a sizeable number of her former boys and their families.

Today, only fragments remain to remind of her presence apart from the remains of the bandstand in Kidston Park.

A move to restore the bandstand to its former glory failed a few years ago.

Cumberland Terrace survives, with Woodside, again a private house, almost opposite in Rhu.

Within Rhu Parish Church the war memorial has found a permanent home but it is outside in the churchyard that the most poignant memorials survive.

As well as headstones marking the graves of individual members of staff, there is a large monument, commemorating all of the boys and staff who died, either through illness or accident while serving aboard the Clyde Industrial Training Ships.

In postscript, for those seeking information on possible family members who served in the ships, regrettably none of the muster rolls appears to have survived.

There is a complete collection of annual reports held in Glasgow’s Mitchell Library, listing the identities of staff, but with only scattered mention of individual boys.