IT IS remarkable enough that two world famous writers both taught at Helensburgh’s former Larchfield School, now part of Lomond School.

But both actually wrote brief poems for one of their burgh pupils.

Professor Malcolm Baird, son of TV inventor John Logie Baird and president of Helensburgh Heritage Trust, found out about it in his youth through his Sunday School teacher who died in 2014, Desmond Wright.

and W.HAuden.

Professor Baird said: “Norman was at Larchfield when Auden and Day Lewis were on the staff, and he was the subject of doggerel poems by them.

“This is the reverse of the usual pattern whereby the pupils write doggerel about the teachers!”

The poems, which came to light in 2013, are off-the-cuff rhymes in stark contrast to the more celebrated works of the two men.

They used rhymes no more sophisticated than those of an amateur, and were scribbled in Norman’s brown leather autograph book.

They remained unseen and unpublished for more than 80 years, but came to light when the book was sold at auction in London by Bonham’s for £3,215.

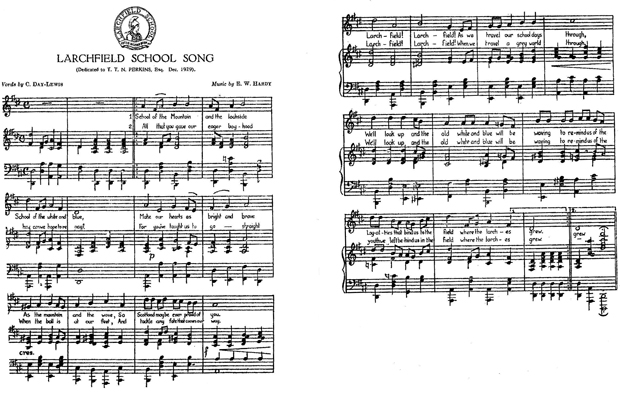

Day-Lewis and Auden both taught Norman at what was then Larchfield Academy in 1930. Day-Lewis also provided the words for the Larchfield School song (see below).

The Auden poem stretches to 16 lines addressed to the pupil.

It begins: “Listen, Norman Wright/Do you want a fight/That you’ve just taken a bite/Out of my ear not slight”, and concludes: “If I catch you tonight/I’ll shoot you on sight/So you’d better take flight/ To the Isle of Wight.”

A reply, written by Cecil Day-Lewis, later to become Poet Laureate, continued in the same vein.

The nine-line verse ends: “To ignite/ Sticks of dynamite/Is not the chief delight/of Norman Wright/Which is proved by the fact that he is still in sight.”

The poem, publicly unseen until 2013, was signed “Cecil Day-Lewis”, and the book was kept proudly by Norman until his death. Later it passed to the private collection of scholar Roy Davids.

Mr Davids said: “To have two such notable poets signing one schoolboy album is remarkable in itself, but this has poems composed especially for the occasion.”

Professor Baird said: “It is a funny old world, with Norman, later a pillar of the church, having been taught by these two somewhat revolutionary figures — although Day-Lewis was more of an establishment figure in later years.”

The Bonham’s sale catalogue stated that Auden taught at Larchfield from April 1930 for fifteen months where he said he was ‘very, very happy’.

With the album was an illuminating typed note by Norman Wright who was at the school from 1928 to 1932. He wrote: “Auden was not a favourite master.

“He was rather uncouth, bit his fingernails to the quick, smoked heavily and spluttered when he spoke. He threw bits of chalk at us when need arose.

“To a young boy I thought his language was somewhat strong. He introduced a reading book for our English tutelage which, when I took it home, my father banned and, as he was a director of the school, he had it withdrawn.

“I do not remember what it was — perhaps something like Dante’s Inferno. He was a laughing-stock on the rugby field with long shorts and white knees and a bit breathless.”

Auden’s poem in the book was first published by The W.H. Auden Society in April 1988, but Day-Lewis’s poem was presumably never intended to be published.

Professor Baird says that Norman’s small place in literary history is reflected in a 1997 book called ‘The Thirties — Modernism and after’.

A chapter on Auden in Helensburgh was contributed by Professor Stan Smith of Dundee University and later Nottingham Trent University, an expert on Auden who had corresponded with Norman.

The Helensburgh influence is strong in Auden’s lengthy work ‘The Orators’, and Professor Baird now plans to read the poem to see if he can discern any more burgh connections.

He added: “My cousin, Arnold Snodgrass, who died in 1962, knew Auden but did not like him. He got along better with Day-Lewis.”

‘Journal of an Airman’, which is part of ‘The Orators’, features the former burgh firm of Macneur & Bryden, publishers of the Helensburgh and Gareloch Times.

Auden, who was in his early twenties, wrote about a huge obituary for the firm’s founder, ex-Provost Sam Bryden, who had died at the age of 80, published on August 26 1931.

Wystan Hugh Auden was born in York in 1907, the son of George Augustus Auden, a distinguished physician, and his wife Rosalie Bicknell.

He was brought up at Solihull in the West Midlands, and educated at St. Edmund’s Hindhood and then at Gresham’s School, Holt, Norfolk. In 1925 he entered Christ Church, Oxford.

His studies and writing progressed without much success, and he gained a disappointing third-class degree in English. His first collection of poems was rejected by T.S.Eliot at Faber & Faber.

At one time in his undergraduate years he planned to become a biologist. From 1928 to 1929 he lived in Berlin, where he took advantage of the sexually liberal atmosphere.

After returning to the United Kingdom, Auden taught at Larchfield from 1930-32, and at Downs School, Colwall, Herefordshire, in 1932-35.

He was a staff member of the GPO Film Unit from 1935-36, making documentaries such as ‘Night Mail’ (1935).

In 1936 Auden travelled in Iceland as he believed himself to be of Icelandic descent. From then on he taught and travelled in both Europe and America, and from 1956-61, he was Professor of Poetry at Oxford University.

He is regarded by many as one of the greatest writers of the 20th century. His work is noted for its stylistic and technical achievements, its engagement with moral and political issues, and its variety of tone, form, and content.

The central themes of his poetry were personal love, politics and citizenship, religion and morals, and the relationship between unique human beings and the anonymous, impersonal world of nature.

He died in Vienna in 1973 and was buried in Kirchstetten, where he had owned a farmhouse.

Cecil Day-Lewis was born on April 27 1904, at Ballintubbert in what was then Queen’s County, today County Laois, in the Midlands of Ireland.

His father, Frank, was a Church of Ireland clergyman, his mother Kathleen a nurse until their marriage in 1901.

The Day-Lewis family moved to England in 1906, first to Malvern in Worcestershire, and then to Ealing in west London, where in 1908 Kathleen died of cancer.

Frank Day-Lewis was devastated by her loss but bottled up his grief. He was unable to talk of his dead wife to their son. His attempt to be both mother and father led to what Day-Lewis later called ‘smother-love’.

After attending prep school in London, the boy was relieved to escape his father to attend Sherborne School in Dorset as a boarder.

In October 1923, he went up to Wadham College, Oxford, but he was not a distinguished scholar, and decided early on to dedicate himself to poetry.

In his final year, 1927, he met and became friends with fellow student Auden, and their lives were to follow similar patterns.

In the early 1930s, Auden and Day-Lewis and others became celebrated as the ‘Poets of the Thirties’. Their political verse, modern in industrial imagery but traditional in form and against the prevailing Modernist mood of the time struck a chord with the public.

In the early 1930s, Auden and Day-Lewis and others became celebrated as the ‘Poets of the Thirties’. Their political verse, modern in industrial imagery but traditional in form and against the prevailing Modernist mood of the time struck a chord with the public.

By 1938, however, Day-Lewis had grown disillusioned with revolutionary ideas, had seen the failure of the Leftist cause in the Spanish Civil War, and heard reports of the brutal reality of life in Stalin’s Soviet Union.

He moved his first wife, Mary, daughter of one of his schoolmasters, and his two sons, Sean and Nicholas, to Musbury on the Devon-Dorset border.

With the outbreak of war, he tried to join the Ministry of Information, but then signed up instead for the local Home Guard.

His divided heart over the war soon became a divided heart in his private life too. He fell in love in 1941 with the novelist, Rosamond Lehmann.

They spent most of the rest of the decade living together, with Day-Lewis making regular trips to his wife and growing children back in Devon.

In 1948, he met and subsequently fell in love with a young actress, Jill Balcon. In 1950 he left both his first wife and Lehmann and the following year married Balcon.

They had two children — the documentary-maker and cookery writer, Tamsin Day-Lewis, in 1953, and the Oscar-winning actor, Daniel Day-Lewis, in 1957.

The detective novels he had been writing since 1935 under the pen-name Nicholas Blake were popular and admired.

He was a distinguished broadcaster on the BBC, reading poetry, and in 1951 he was elected Oxford Professor of Poetry. He died of cancer on May 22 1972.

The Larchfield School song, supplied by Andrew Widdowson, son of past headmaster the late John Widdowson.