THE OLD saying that if you go down to the woods today you are sure of a big surprise certainly rings true for a very successful Helensburgh and district group of enthusiasts about the area’s heritage.

Actually members of the burgh-based North Clyde Archaeological Society more of than not go up to the woods and indeed the summits of local hills in their quest for relics of days long gone by.

Their searching has been rewarded with many fascinating finds, some of which have been on show in Helensburgh Library and Helensburgh and Lomond Civic Centre in recent months.

Chairman Tam Ward from Rosneath: ‘The aims is to show the public direct evidence of past human activity in the area, ranging from the times of our remote forebears through to the Victorian era, and to give a flavour of some of the ambitions of the society.

“Historical records can take us so far, but sometimes it is only through archaeological work that we can catch a glimpse of how and where people were living at one time, and — vitally — what they were doing in their day to day lives.”

Some of the oldest material was obtained by the process of field-walking, where the turning over of the ground through agricultural and forestry activities has thrown up signs of man's early presence.

The slopes of Ben Bouie above east Helensburgh provided artefacts of flint, jet and cannel coal, none of which occur there naturally, and which can only have been brought there by humans.

Material like this implies the presence of prehistoric man on our doorstep, though it is evidence that can so very easily go completely unnoticed and unknown.

By far the greatest amount of material to be on display, however, is more recent, and stems from the single biggest dig carried out by the society at Millbrae, between Rosneath and Kilcreggan.

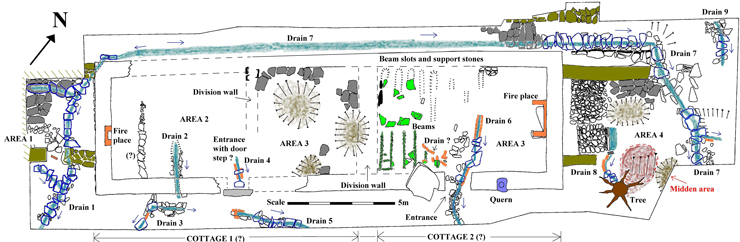

The site is shown on the plan above, and work has just started on further exploration there.

Set amid the slopes of a commercial forest, the site was once that of an extended cottage, latterly consisting of two households.

Set amid the slopes of a commercial forest, the site was once that of an extended cottage, latterly consisting of two households.

While written records suggest occupancy from about 1750 until shortly after 1860, the excavation offered tantalising clues that people were living at the site for quite some time before the proven historical date.

Local historian, Helensburgh Heritage Trust director, and society member Alistair McIntyre said: “The great thing about the finds are that they help bring history alive, taking us well beyond the realm of the dry and dusty archive.

“The ambition is to provide powerful and thought-provoking insight into the day-to-day lives of the people who were living at Millbrae.”

The artefacts found there include simple things like buttons, a watch-wheel, fragments of a tea-pot, a whisky flagon, a spoon, the heel of a shoe, and a clay pipe — one fine example shows a sailing ship on one side of the bowl, and an anchor on the other.

The artefacts found there include simple things like buttons, a watch-wheel, fragments of a tea-pot, a whisky flagon, a spoon, the heel of a shoe, and a clay pipe — one fine example shows a sailing ship on one side of the bowl, and an anchor on the other.

Evidence was found of the presence of children, with 20 marbles scattered across the site, and the almost miraculous survival of a piece of fabric, thought to be perhaps part of a child's bonnet.

The people who lived at Millbrae were for long gamekeepers on the Duke of Argyll's Rosneath estate, and symbols of work and livelihood found include a horseshoe, chisel, bill hook, and musket balls and gun-flints.

There was evidence inside, with sheared-lip ink bottles and samples of bulls-eye window glass, allowing the interior to be lit well enough for writing and other activities.

The residents also showed a sense of style, ranging from attractively patterned, hand-painted crockery to ladies hatpins.

All the surveys and digs conducted by the society, which was formed in 2013, have been carried out by volunteer labour, working under the highly-experienced and watchful eye of Tam Ward.

A veteran archaeologist with over 30 years experience, he moved to Rosneath several years ago.

He is best-known for his pioneering work in Upper Clydesdale, including the discovery of Mesolithic encampments and excavations of defensive farmsteads known as bastle-houses.

His reputation has brought him into contact with such media luminaries as Tony Robinson and Alice Roberts, resulting in several TV appearances.

Alistair says that, as an unskilled volunteer, he has found working at places like Millbrae provided the excitement of never knowing what the next scrape with the trowel will reveal, yet within the framework of an organised approach. “There is ample opportunity to improve skills and knowledge, and at the same time do so with the added benefit of healthy exercise in the fresh air,” he said.

“You are working close to nature too. At Millbrae a robin was a constant companion, a kestrel occasionally hunted overhead, and one day there was a gathering of 27 herons at the Mill pond.

“You had to be careful when shifting stones, in case there was something like a newt sheltering underneath — quite a few were removed and carefully placed elsewhere.

“Then there was the pleasant surprise of seeing primroses and other flowers blooming in January.”

Millbrae proved to be a variable site. Some of the walls were really well-built, but others were shockingly sub-standard. Some water-drainage channels were well constructed, while others looked tailor-made to choke up. In places, stone flagstones were of high quality, but in another part extremely shoddy.

In one room, remains of wooden flooring boards amazingly survived, but it could be clearly seen that they had been laid directly on top of soil — not a particularly good idea.

But despite the questionable building standards, the pottery remains were of reasonable quality, and the inhabitants had certainly not lacked for fuel. There were masses of coal dross everywhere, and there was the luxury of an ornate cast-iron fireplace.

But despite the questionable building standards, the pottery remains were of reasonable quality, and the inhabitants had certainly not lacked for fuel. There were masses of coal dross everywhere, and there was the luxury of an ornate cast-iron fireplace.

The whole building looked to have been built as a single entity, with various clues pointing to a construction date around the start of the 19th century.

The walls were mainly of stone, but a few hand-made bricks were also incorporated. The roof must have been thatched, as evidence of slates or tiles was almost non-existent.

Care was taken to try to locate traces of earlier structures on the site, but none was found.

However Tam said that the evidence seemed to point clearly to earlier human presence.

A main wall had as part of its construction a quern, which is a hollowed-out rock used for grinding corn. Something like this would not have been moved far from where it was originally put to use.

He said: “In other words, it suggests that people had been living close by, prior to the existing building.

“Tellingly, there were also pottery sherds of green-glazed ware and necks of bottles not far from the buildings, which looked to be possibly as old as late 17th century.

“Specialist help will be sought to help pin down dates more precisely — a necessary but costly and time-consuming part of the whole process.”

He said that the site proved extremely challenging. When the previously open hillside was planted with Sitka spruce about 40 years ago, furrows were made through the site, and trees planted right on top of the ruins.

By the time of the excavation, the trees had been harvested, but many huge stumps remained.

Alaistair said: “You might wonder how Tam, along with Sandra Kelly, ever managed to locate the site in the first place. One clue came from the presence of several mature holly trees close together, while pottery sherds and a scatter of bricks on the surface provided further encouragement.”

The present land managers, Tilhill Forestry, along with their sub-contractor, were very helpful in preparing the site. A machine was made available to remove stumps and brush carefully.

While the site itself has been preserved, thanks to the dig, the hillside round about has already been replanted with Sitka spruce, and in a few years time Millbrae will once again disappear from view until the next round of harvesting in 40 years time.

While the site itself has been preserved, thanks to the dig, the hillside round about has already been replanted with Sitka spruce, and in a few years time Millbrae will once again disappear from view until the next round of harvesting in 40 years time.

A walkover survey of the surrounding hillside revealed evidence of structures known as burnt mounds, as well as a slag heap, where it looked as though iron had been smelted.

Once again, specialist advice and radiocarbon dating may help confirm the significance of these finds.

“There is a definite possibility that these discoveries will be firsts for the Rosneath Peninsula,” Tam said.

The society runs a regular programme of talks, digs and surveys, with summer excursions to sites further afield.