A RHU village schoolteacher had a sideline of money-lending — and it led to his murder.

Dominie John Arroll became the focus of a mystery.

In those days teachers often took on other work which required literacy and numeracy in order to supplement their income.

By 1759 Arroll, who was 52, was session clerk of Row Church and he was also honourably regarded as banker to the neighbourhood.

Telling the story in the Helensburgh Heritage Trust book ‘200 Years of Helensburgh’, editor Stewart Noble said that Scotland’s three banks confined their business to larger towns.

“Not only did Arroll look after the savings of the people, but he also lent money out at interest when he saw a safe opportunity to do so,” he wrote.

“Unfortunately not all borrowers could be relied on to repay their debts promptly and in full.”

He had lent money to a Dumbarton man called Cunningham and was owed £30, a considerable sum in those days.

Having given notice that he wanted the money back and having heard unfortunate reports about Cunningham, he set off one day in January 1760 to collect the debt.

He got there safely, was seen by many people in the company of Cunningham during the day, but he failed to return home that night.

Within a few days the alarm was raised and many of the Row inhabitants searched the area for him, but in vain.

Three weeks later his body was found floating in the River Leven near Dumbarton Castle. A knife wound, probably straight into the heart, was the cause of death.

No money or valuables were found on the body, which had fairly recently been placed in the river as the inside of his pockets were dry.

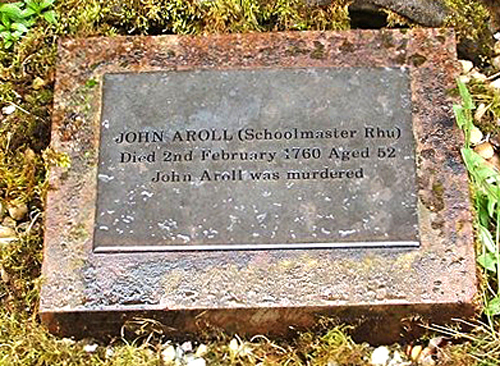

He was buried in Dumbarton Parish Churchyard, now Dumbarton Riverside Church, and legend had it that no grass would grow on his grave.

However it is thought that the number of people wanting to look at the grave prevented the grass growing,

From the start Cunningham was suspected of the murder, but there was no evidence against him.

Stewart writes: “In those days it was believed that if the murderer merely touched the body of his victim, the wound would bleed.

“Cunningham was given the opportunity of proving his innocence, but on the advice of his friends he declined to undertake the test, not because they feared for his innocence, but because it was also believed that the body would bleed if touched by a man who had shaved on a Sunday!

“To try to overcome this objection, the Rev John Freebairn, the minister of Dumbarton Parish, offered to touch the body having previously admitted that he shaved on a Sunday.

“At Mr Freebairn’s touch the body did not bleed. Consequently it was suggested once more to Cunningham that he could prove himself innocent by touching the body, but he resolutely declined.”

Nothing further happened for many years, but on his deathbed Cunningham confessed at last that he was the murderer.

He said that he had repaid the £30 to the schoolmaster and got a receipt for it, but then he stabbed him.

He robbed the body and then he hid it up a disused chimney in his house where, shortly after, it was discovered by his servant girl. She got such a shock that she went mad.

Cunningham admitted that he carried the corpse to the river one dark night, then breathed his last.

Dr Ian M.MacPhail, the Dumbarton historian, commented that the story of Arroll’s tragic death “throws an interesting light on the manners and customs of the period.”

More background about the schoolmaster comes from the 1883 book ‘A Nonogenarian’s Reminiscences of Garelochside and Helensburgh and The People who Dwelt Thereon and Therein’, an account written by Donald MacLeod of details supplied by his uncle, Gabriel MacLeod.

Gabriel stressed the importance of the school to the village, although he recorded that schoolmasters were paid miserably.

He said: “The school was common ground on which met the son of the laird and the son of the cottar, and it thereby created a healthy feeling between the different ranks of society.”

In 1759 Killearn-born John Arroll had already been in post in ‘the Row’ for a number of years at stirring times in the country’s history.

“He had seen the Rebellion of ’45, watched with deep interest the sudden rise of the young Chevalier’s fortunes, and their equally sudden collapse, with the destruction of all the long-cherished hope of the Jacobite party,” Gabriel said.

“Whatever John Arroll’s sympathies were, he carried no sword and wore no cockade, and he swore allegiance to King George, the third of that name, on his accession to the throne of the kingdom.”

Gabriel said that as a parish schoolmaster Arroll was bound to be a loyal subject of the king.

He continued: “Besides, he was a man somewhat advanced in years, in whom youthful enthusiasm in all probability was toned down considerably, and who would therefore be very guarded in the expression of his opinions.”

Personally, as he occupied the very honourable position of banker to the Row parish and neighbourhood, he had too much at stake to ally himself to the malcontents.

He was not only the custodian of the small savings of economical farmers and fishermen, but he lent the same at fair interest in the interests of his customers when a safe outlet for the money presented itself.

Gabriel said: “My grandfather, who resided in Row Parish, was one of those who so trusted him with his savings, and he lost his little all by Arroll’s tragic end.

Gabriel said: “My grandfather, who resided in Row Parish, was one of those who so trusted him with his savings, and he lost his little all by Arroll’s tragic end.

“That Arroll occupied such a position of trust showed the confidence and esteem in which he was held by the parishioners — a confidence which many years of upright conduct in the discharge of his trust had considerably strengthened.”

John Arroll married Janet McAuley from Cairndow, Argyll, at Row, and they had two sons, John, who was born around 1739, and James, born some two years later.

He was succeeded as Row schoolmaster by James, who is buried in the village churchyard.

After his death, relatives and friends wanted to take his body back to Row for burial, but the Dumbarton authorities compelled them to bury him in the parish he was found.