The text and illustrations below are the entire contents of a leaflet compiled and published in 1955 by David McRoberts, giving the history of the Chapel of St Mahew at Cardross. The leaflet was donated to Helensburgh Heritage Trust in 2010 by Gillian George.

ABOUT a quarter of a mile to the north of Cardross village, in Dunbartonshire, lies a small parcel of land called Kirkton of Kilmahew.

It is a pleasant place, where, among ancient trees, one looks out across the broad Firth of Clyde to upland hills of Renfrewshire and the more distant mountains of Cowal.

For a generation or two this property has consisted of a derelict graveyard surrounding the ruin of a small mediaeval chapel.

In 1948 the place became the property of the Archdiocese of Glasgow, and these new owners decided to restore the ruined chapel of Kilmahew so that it might play once again a vital part in the life of the neighbourhood.

The following pages will give a brief account of the long history of Kirkton of Kilmahew, from its foundation in the dawn of Scottish Christianity, through alternating periods of prosperity and ruin, down to its happy resurgence in the year 1955.

The history books, which tell us the names of the great saints who brought the Gospel of Christ to these northern lands, only too often give the impression that instantaneous and universal success followed the efforts of these apostles.

We generally forget the century or two of strenuous labour by which the disciples of these earliest apostles consolidated the work, bringing Christianity into every corner of the land and weeding out forever the stubborn pagan customs and beliefs of the newly converted peoples.

Along the west coast of Scotlanjd, this task of building up a Christian people was largely the work of missionary monks from the great monasteries of Ireland and Scotland.

The frail coracles of these monks plied the western seas from Brittany to the Shetland Isles, and dotted along our coasts are the tiny settlements from which their influence permeated each clan and district.

Nowadays, these centres of early Christianity are too often forgotten. A place-name keeps alive their memory and perhaps a primitive standing-stone, carved with the distinctive interlaced pattern and the Cross of Christ, speaks of the ancient sanctity of the place.

The settlements or Cills of the Celtic monks had an apostolic simplicity about them.

Alongside a graveyard, consecrated for Christian burial, stood an oratory, built of wood or dry-stone, where the Sacrifice of the Mass was offered. There was a hut where the monk dwelt. A stone, carved with the Cross, proclaimed the faith of Christ.

That was about all, but what the place lacked in material equipment was more than made up for by the burning faith and zeal of the missionaries who dwelt there.

In the dawn of Christianity in Strathclyde, Kirkton of Kilmahew was just such a centre of missionary enterprise.

The title of the site, Kilmahew (which name has long since been extended to the whole surrounding district), tells us that the place was a Cill, or church, founded by St Mahew.

The name Mahew is a form of Mochta, and there are several saints of that name in the old records of the Celtic Church.

It is possible for us to identify the St Mahew, or Mochta, of Kilmahew from information provided by the early 17th century Scottish writer, Thomas Dempster.

Dempster, deriving his information from pre-Reformation breviaries, describes him as “Mahew, a prophet and a disciple of St Patrick, the Apostle of the Irish people”, and he adds that his feastday was celebrated in Bute on 11th April and in Dunkeld Diocese on 5th October.

It would seem then that our St Mahews is to be identified with St Mochta of Louth. This St Mochta was a Briton and a convert from paganism. He came to Ireland early in life and became one of St Patrick’s followers: in fact, it is quite possible that, like St Patrick, he was a native of this district.

St Adamnan of Iona speaks of his gift of prophecy. Mochta founded an important monastery at Louth and gained a great reputation for sanctity. According to the Annals of Ulster, he died in the year A.D. 535.

St Mochta’s monastery at Louth remained an important ecclesiastical centre for generations after the founder’s death and it continued to send out missionary monks, far and wide, to establish new centres of Christian life.

One of these places, founded by St Mochta in person or by his monks, was Kilmahew — the Cill of Mahew or Mochta.

The first ecclesiastical foundation at Kirkton of Kilmahew would be an unpretentious affair, like the similar foundations elsewhere along our western coast.

There is slight evidence that here, as in some other instances, we have an earlier pagan sanctuary where the Christian monk boldly established his missionary activities.

We are told that St Patrick was wont to carve the symbol of the Cross on pagan monuments in Ireland, in order to emphasise the victory of Christ over heathenism, and, no doubt, his disciple, St Mahew, followed his example.

This practice gives particular interest to a very primitive stone monument which was dug up in 1955, during the work of restoring the church. This monument is the top part of an ancient standing-stone, on which has been crudely incised the shape of the Cross.

This “Cross of Saint Mahew” probably dates back to the earliest Christian foundation at Kilmahew and it has been carefully re-erected in the vestibule of the restored church.

This “Cross of Saint Mahew” probably dates back to the earliest Christian foundation at Kilmahew and it has been carefully re-erected in the vestibule of the restored church.

St Mahew and his contemporaries passed away, but the Cill of St Mahew remained a holy place to the people of the whole neighbourhood. As generation followed generation, the little church was repaired and replaced, time and again, and men sought the privilege of burial in the holy ground beside it.

In 1955, as the work of restoration proceeded, there were found fragments of these ancient tombs: on one of them, which dated back to the tenth or ninth century, was carved some of that Celtic interlaced pattern so characteristic of the monuments of our distant forefathers.

The earliest surviving documents which actually speak of the chapel of Kilmahew are two charters of the reign of King David II (1329-1370). In one of these, King David grants to Roger Cochran the lands of Kilmahew “with the chapel thereof”.

Sometimes later, William Napier, whose family had been established in the district for about a century, obtained from King David II the half lands of Kilmahew, “where the chapel is situated”.

The chapel of Kilmahew was apparently an important landmark of the district in the early Middle Ages and, that being the case, it is not too fanciful to suggest that the great hero-king of Scots, Robert the Bruce, during those years when he lived in retirement at Cardross Castle, some three miles away, may on occasion have listened to the impatient barking of his hunting dogs as he knelt at Mass in Kilmahew Chapel, remembering the men who fell at Bannockburn or praying for the welfare of the Scottish nation.

During the later Middle Ages the lands of Kilmahew remained in the possession of the family of Napier. The venerable walls of the castle, which was their home, still rise proudly half a mile away to the east of the chapel.

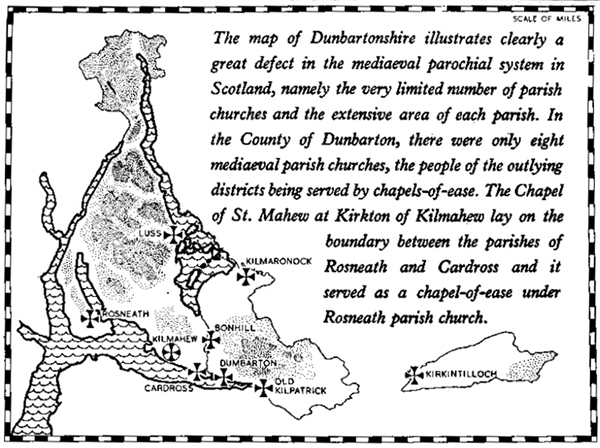

The people who dwelt on Napier’s lands were badly served under the mediaeval parochial system of Scotland. They were right on the boundary of Cardross Parish, the parish church of which was about three miles away: the next neighbouring parish church, that of Rosneath, lay some seven miles away across the waters of the Gareloch.

The famous 16th century Scottish scholar, John Major, complained about the bad distribution of parish churches in Scotland, where the parish church was often so far way that it was necessary for “every wee laird” (infimus quisque dominus) to maintain a chapel-of-ease for the spiritual welfare of his own people, because they lived at too great a distance from the mother-church of the parish.

This was the situation at Kilmahew, where the Napier family maintained the old chapel at Kirkton as a chapel-of-ease, under Rosneath parish church, for the benefit of the people of the district.

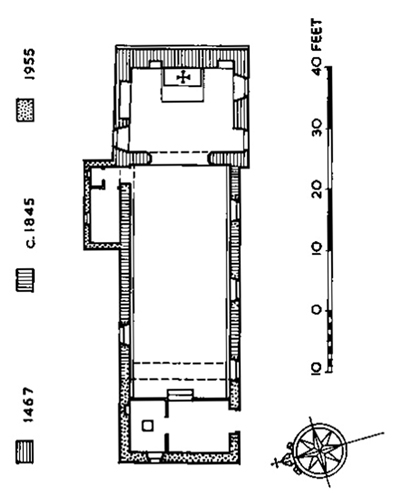

Early in the reign of King James III, Duncan Napier of Kilmahew decided to rebuild the chapel at Kirkton. This rebuilding was completed in 1467, and it is the ruin of this chapel that has now been restored.

Enough of this building has survived to give us a picture of the chapel as it stood in the later 15th century. It was a plain, harled building, excellently proportioned, with square-headed windows and doors.

Crow-stepped gable marked where the chancel roof rose slightly above the longer roof of the nave. Some sculptured coats of arms embellished the more prominent architectural features.

The south skew-puts of the chancel carried shields, of Renaissance design, showing respectively the I.H.S. monogram of Our Lord and the initials M.C., which stood for Mater Christi or Mother of Christ.

Duncan Napier’s own coat of arms would appear somewhere on the nave. It was a building perfectly suited to its rural setting. Internally, the chapel was about 48 feet in length; its chancel or sanctuary, being separated from the nave by a rounded arch which held the wooden chancel-screen.

The chancel was well equipped: its altar would have a rich cloth frontal and an altarpiece, which was probably imported from Flanders. At the gospel side of the altar stood the Sacrament House or tabernacle (which remains to this day and is one of the best specimens to have survived in the south-west of Scotland).

In the north wall of the chancel the founder’s tomb was placed so that its alcove could be used for the Easter Sepulchre. In the nave stood the Baptismal Font, securely locked in accordance with synodal decrees. The Rood Loft supported the Great Rood over the chancel arch.

Above the chancel, with its entrance from the Rood Loft, was the Chaplain’s Chamber: this was a fairly spacious room with a little window which looked out over the Priest’s glebe to the east.

It must surely have been a proud day for Duncan Napier and his people when, on the Sunday within the Octave of the Ascension, 10th May 1467, they all gathered at Kirkton for the consecration of the rebuilt church of St Mahew.

The Bishop of Argyll, George Lawder, performed the ceremony, having received permission to do so from Bishop Andrew Muirhead of Glasgow.

It is easy to follow, from old service books, the consecration of St Mahew’s Church: the colourful procession, in which the aged Bishop, wearing cope and mitre and leaning heavily on his crozier, walked with his attendant priests around the church to bless and anoint the consecration crosses, which were built into the walls.

It is easy to follow, from old service books, the consecration of St Mahew’s Church: the colourful procession, in which the aged Bishop, wearing cope and mitre and leaning heavily on his crozier, walked with his attendant priests around the church to bless and anoint the consecration crosses, which were built into the walls.

There followed the solemn ritual of enshrining the relics of the martyrs in the altar and then, when the altar had been consecrated, the pause in the ceremony when Duncan Napier, the patron of the chaplaincy, went forward and laid on the newly consecrated altar the symbolic staff, which represented his endowment of the church, which was, in this case, an annual rent of forty shillings and tenpence from certain tenements in Dumbarton.

The bishop then addressed the people on the importance of the ceremony, announced the date on which the Feast of Dedication should be observed each year in perpetuity, and then followed the first Pontifical Mass in the new church.

The remainder of the day, we can be sure, saw much feasting and merriment at the castle.

For a century, the new church was the spiritual home of the people. The history of the chaplains who succeeded one another at Kirkton has been forgotten, except for one incident in 1526, when the vicar of Cardross parish church, William Brunsyd, made a contact with David Graeme, the chaplain of Kilmahew, to exchange their respective appointments “and yis presentatioun to be maid as sone as ye Laird of Kilmahew can make the said Sir David fyrme and sikkyr of ye said vicarage of Cardross”.

In the mid-16th century, the chaplain living in the priest’s chamber at Kirkton Chapel must have given much anxious thought to the religious and political situation.

The uncertain course of the Religious War ended, at length, in a Protestant victory and, at Kilmahew, after a time, the sanctuary lamp flickered out, the priest had gone, the old familiar music of the Mass was silent.

In 1574 a Reader named Adam Hutcheson conducted worship at St Mahew’s Chapel according to the new manner, on behalf of the minister of Rosneath.

The chapel seems to have become derelict in the early 17th century and, in 1640, Robert Napier of Kilmahew offered to the heritors of the parish the use of the chapel as a parochial school.

In this document, which still exists, he gave the use of the nave only and he retained the chancel as the family burial-place. The chancel arch was built up to separate the nave, with its scholars, from the chancel, with its tombs, and when this dividing wall was taken down in 1953, there was discovered, carefully bedded in the foundation, the top section of the mediaeval Baptismal Font.

The Baptismal Font has now been re-erected in the church and restored to use.

At one moment it looked as if Kirkton Chapel would become the parish church of Cardross. The new village of Cardross had grown up on Kilmahew lands and the people complained of the distance to the parish church, which was three miles away on the banks of the River Leven.

The Presbytery met, on 12th September 1643 in Kirkton Chapel, to discuss the matter, and in spite of the fact that several were in favour of using Kirkton Chapel as the parish church, a completely new site in the village was finally decided on.

The Session Records give occasional glimpses of life in the village school, which remained established in Kirkton Chapel from 1640 to 1846.

There are complaints, from time to time, about the ruinous state of the structure, and assuredly the floor boards must have been very defective at the end of the 17th century to account for the number of Charles II coins that were discovered in the subsoil.

By the 19th century the complaints had increased, and eventually, in 1846, the school was transferred to a new building in the village and the old chapel at Kirkton of Kilmahew was abandoned.

The property then passed through various hands and, in 1948, it was acquired, as part of the Kilmahew Estate, by the Archdiocese of Glasgow, and the new owners eventually decided on its complete restoration as a church.

The work began in 1953, under the direction of Ian G.Lindsay and Partners of Edinburgh and was brought to a successful conclusion within the Octave of the Ascension, 22nd May 1955, when the Archbishop of Glasgow, the Most Reverend Donald A.Campbell, D.D., celebrated in it the first Pontifical Mass after a lapse of some four centuries.

The Chapel of St Mahew, which has been restored, is structurally the church which was built in 1467. A small vestry has been added on the north side and the nave has been extended by a few feet at the west end, where a small belfry now crowns the gable.

The venerable “Cross of Saint Mahew” stands in the vestibule. A new altar, furnished in 15th century style with painted altarpiece and splendid cloth of gold frontal, takes the place of the ancient altar.

The original Sacrament House and Baptismal Font are brought into the scheme of restoration. A new chancel screen and Rood Loft replace these mediaeval features.

An inscription across the Rood Loft tells of the restoration of the cburch: HANC PERANTIQUAM SANCTI MACCAEI ECCLESIAM VETUSTATE DIRUTAM DONALDUS ARCHIEP. GLASGUEN. RESTAURANDAM CURAVIT PIEQUE EXORNAVIT A.D. MCMLV.

The translation is: “Donald, Archbishop of Glasgow, caused this venerable church of St Mahew to be restored, after it had fallen into ruin in the passing of the years, and piously he embellished it, in the year of Our Lord, 1955.”

In addition to the Great Rood, with its attendant figures of Our Lady and St John, the Rood Loft displays six coats of arms: the coats of arms of Pope Paul II, Bishop Andrew Muirhead of Glasgow and Bishop George Lawder of Argyll recall the consecration of the church in the year 1467; while the coats of arms of Pope Pius XII, Archbishop Donald Campbell of Glasgow and Bishop Kenneth Grant of Argyll and the Isles commemorate the restoration of the church in 1955.

At the foot of the Great Rood, linking together the two groups of shields, is the coat of arms of Duncan Napier of Kilmahew, whose pious work has survived the bewildering changes of five hundred years.

At the foot of the Great Rood, linking together the two groups of shields, is the coat of arms of Duncan Napier of Kilmahew, whose pious work has survived the bewildering changes of five hundred years.

We who looked on, as this ancient sanctuary took on new beauty and new vitality and quietly resumed its immemorial task of hallowing the lives of men, came to realise, as never before, how deeply our roots lie buried in the past, and we pray that the work of St Mahew and of Duncan Napier may yet flourish and prosper.

“O King of Ages bless this house

And keep it free from scaith,

That from this place may shine anew

Printed in Great Britain

At Hopetoun Street, Edinburgh,

By T. and A.CONSTABLE LTD.

Printers to the University of Edinburgh