TRAINING SHIPS were a way of life — and a hard one — in the Gareloch from 1869 for 54 years.

But Helensburgh and Rhu benefitted in various ways from the two former sailing ships moored off Kidston Point and the boys who lived on them.

The first of the two ships was HMS Cumberland, after which Cumberland Avenue in Helensburgh and the much older Cumberland Terrace in Rhu were named.

Cumberland Terrace is a two storey building like a row of cottages, built in 1871 and owned at one time by the Clyde Industrial Training Ship Association for commissioned and non-commissioned officer accommodation and to provide a small hospital, and now all privately owned.

The Cumberland, built in 1842 at Chatham, was a 2,214-ton two-deck 70-gun man o'war, 180 feet long, with three masts, and had a crew of up to 620 men. In March 1854 she sailed to the Baltic Sea as war with Russia was imminent — the Crimean War. Cumberland was involved in the attack on Bomarsund, Finland, in August of that year.

In 1869 she was taken over for use as a training vessel by the newly formed Clyde Industrial Training Ship Association.

The Association had the object of providing for the education and training of boys who, through poverty, parental neglect, or any other cause, were destitute, homeless, or in danger from association with vice or crime.

Originally, boys were trained for entry into both the Royal Navy and the Merchant Service. However, after the Royal Navy decided to accept only boys of good character, the training became more orientated towards the Merchant Navy.

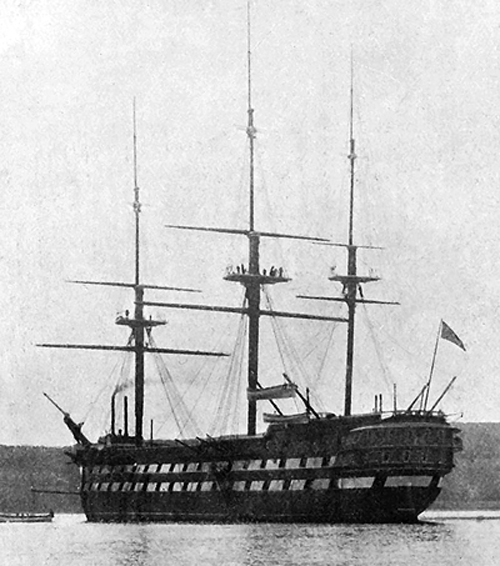

In 1889, the Cumberland was destroyed by a fire, allegedly arson by five of the boys, sold at auction at Robert McTear Auctioneers in Glasgow for £1,770 for scrap, and replaced by the Empress, a wooden battleship originally known as HMS Revenge.

The 3,318-ton Revenge, built in 1859, was 245 feet long and had a complement of 860 men.

Her previous roles had included Flagship of the Channel Fleet in 1863, Second Flagship of the Mediterranean Fleet in 1865, and Flagship at Queenston (1873), as well as coastguard duty at Pembroke and Devonport.

Under the name of Empress she served as the Gareloch training vessel until being sold off in 1923 with, at the peak, 400 boys aboard.

Among the Assocation’s directors was shipowner Sir William Raeburn, the first Baronet of Helensburgh, and among its patrons were the Duke of Hamilton, the Duke of Montrose, the Earl of Home, and the Marquis of Ailsa.

There is debate to this day about how hard life was on the training ships. The routine was certainly rigorous, the day beginning at 6 a.m.

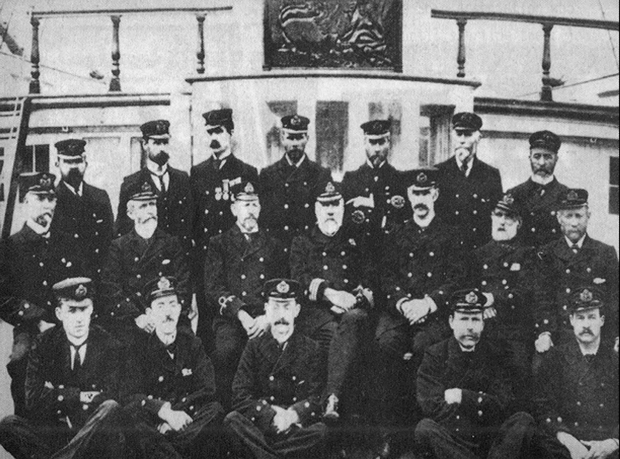

Trainees were taught general education and all aspects of seamanship, including how to hoist the sails and handle the cannon. The officers who ran the ships were experts and firm disciplinarians.

Three times a day the steamer Lucy Ashton passed by and caused the vessel with its makeshift classrooms to roll slightly as she swung on her mooring. For many of the 300 youngsters the pitch from the Lucy’s wake was the only diversion of the day.

The former man-o’-war had been converted at a cost of £5,000, gutted and stripped to cope with the problem of looking after needy boys.

The former man-o’-war had been converted at a cost of £5,000, gutted and stripped to cope with the problem of looking after needy boys.

Many were the waifs and strays of the period. In their smart pseudo naval uniforms they were a common sight around the villages and communities on the shores of the Gareloch.

Many a local youngster on land had the threat thrown at him: “You’ll be sent to the Empress if you don’t behave.”

Disciplined and uniformed, the young boys of the Empress responded to the tawse, the birch and the strict naval code of behaviour. There was no nonsense.

But occasionally some youngster fled the ship, as two or three did one night in a storm. One drowned, and the others were brought back.

The penalty for trying to slip off in one of the Empress’s small boats was not pleasant.

The young culprit was laid — stripped to the waist — across a brass cannon on deck. In front of the Captain, the Master at Arms and the assembled crew — mustered to see the punishment and learn the lesson — the boy was lashed. The permitted maximum was 18 lashes.

A hard life? “Not really, there was no real cruelty on the Empress,” Walter Hargreaves Smith, who taught on the ship, claimed later.

Lancashire-born Walter, later to become a headmaster in Burnley, joined the teaching staff of the Empress in July 1915, his first post after leaving college.

Lancashire-born Walter, later to become a headmaster in Burnley, joined the teaching staff of the Empress in July 1915, his first post after leaving college.

“The lads were between the ages of 11 and 16,” he said. “Some were first offenders, others were there for nothing more than not attending school.

“Life on board was reasonable for the boys. In fact I would say it was very good. It is always a big proposition to cope with 300 boys on board a ship. They were well fed and there was no brutality.”

The Empress had no real classrooms. The 200ft long hall was partitioned off with canvas, and was the place of learning. The boys attended every other day between standing port and starboard watches.

Teaching on board had its own particular problems, one of which was seasickness. “We really had very little of that, but sometimes one did feel a bit squeamish,” Walter said.

“Then there was the old Lucy Ashton passing about three times a day on her way to and from Garelochhead. She used to set us on a bit of a swing each time. We could always tell.”

Walter left the Empress in August 1919, four years before the training ship was decommissioned and towed to Falmouth to be broken up.

Religion played a part in the training of the boys. The honorary chaplain to the ship was the Rev V.C.Alexander, the minister at Rhu.

The Empress seldom moved from her berth in the bay. Only when her moorings required repair was she towed further into the Gareloch.

Walter said that she was well-built, with no dampness, and described her as “one of the walls of England”.

He recalled times when the storms howled so badly that he and the others were unable to leave the ship in small boats for as long as three days. Yet the ship was only a few hundred yards from Rhu pier.

He recalled times when the storms howled so badly that he and the others were unable to leave the ship in small boats for as long as three days. Yet the ship was only a few hundred yards from Rhu pier.

In summer the boys were often brought ashore for sports and games in the field beside the Ardencaple Hotel, and it was called Empress Park. They also had a Boy Scout Troop on board, the 4th Helensburgh Scouts, and they took part in joint camps with other Troops at Shandon.

They had several bands which played at the Kidston Park bandstand and even at local functions. The boys rowed ashore in the ship’s gigs, with eight boys rowing and a coxswain in charge.

In his retirement Walter, who married a Helensburgh girl who predeceased him, was a regular visitor to the Gareloch. He said: “On my return trips I always look out into the bay with a feeling that there is something missing.”

Walter recalled a pupil from Rhu who became a painter and decorator after serving his apprenticeship with a Helensburgh firm, and later became a local councillor. That man was the grandfather of current Rhu resident Iain McKay.

Iain said: “My grandfather ended up on the Empress because of the death of his mother, and the fact that his brothers were all away fighting in the war. He at no time was a truant or a first offender.”

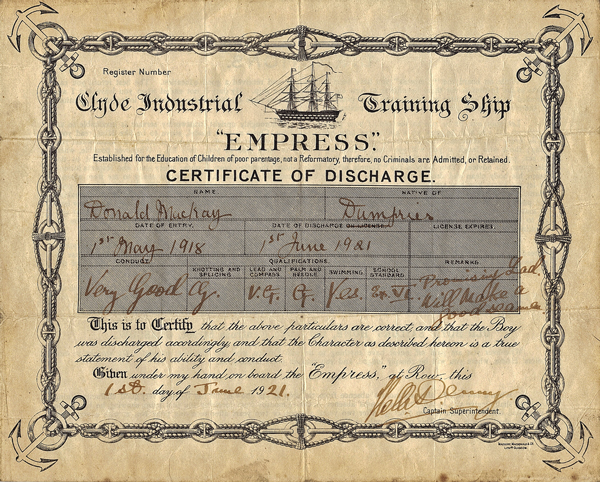

His grandfather, Donald McKay, later served his time as a painter and decorator with McCullochs in Helensburgh. He went on to establish his own business in 1929, and it is still trading today.

He was a local councillor among many other prestigious positions he held in the town, and was a very well respected member of the community.

When he left the Empress he received a certificate of discharge which stated at the top that the Empress was “established for the education of children of poor parentage, not a reformatory, therefore no criminals are admitted or retained.”

Despite what Mr Smith thought, it was a still a very hard life for the boys — as one of them, who wished to remain nameless, wrote later.

Despite what Mr Smith thought, it was a still a very hard life for the boys — as one of them, who wished to remain nameless, wrote later.

He said: “The schoolmaster made it sound like a holiday camp. I can assure you that it was a grim and desperate life for a boy. I know. I was an Empress lad for five frightening years.

“My own father was an old Boer War sergeant. He used to thump me. The James Street school teachers could vouch for that, they often saw me black and blue.

“I had a stepmother, and was often so afraid to go home that one night after playing truant from school I slept in the rain shelter on the seafront. I was 11 years of age.

“The police found me, and that was how my career on the Empress started. I remember Mr Smith coming on board in 1915. He was a young smart-looking man.

“I entirely disagree with him that we were well treated. We were badly treated, fed and cared for. We were bitterly cold in winter with no heating in our part of the ship — but the officers had heating. The food was lousy, and so were many of the boys.

“We only had two blankets and had to roll ourselves up at night to try to keep warm.

“I vividly remember the night watchman. His job was to awaken us twice during every night to make us go to the toilet. He very often used a rope with a turk’s head at the end. It was very frightening for a young boy.

“Of course people in Helensburgh saw us well turned out, and I’ll tell you why. We were issued with boots in November and they were taken away in March. We were only allowed to wear them to go ashore or to the Empress field occasionally.

“One trick was to make you roll up your sailor’s trousers and cross your hands on your bare knees. If the tawse missed your hands it hit your knees, and you never forgot those lessons.

“For breakfast we got water, porridge and bread. Lunch was mash, with some corned beef mixed in. Milk was a luxury as it came from ashore. I was once so hungry that I pulled the carrot out of the bung-hole of a barrel of milk and ate it!

“For breakfast we got water, porridge and bread. Lunch was mash, with some corned beef mixed in. Milk was a luxury as it came from ashore. I was once so hungry that I pulled the carrot out of the bung-hole of a barrel of milk and ate it!

“There was never anything like an egg or ham or anything like that. You had to rely on parcels from relations, and these were always opened and searched before you got them.

“I remember us being de-loused with a hose, then painted yellow with a whitewash brush after Dr Sewell of Helensburgh had visited us. There was eczema too, and a lot of the boys left ill and I do not know where they went.

“I remember that medical inspection. I was one of the boys detailed to burn the clothes in the boiler room.

“I was five years on that ship, five years I will never forget. I held the highest honour for behaviour, the gold star on my sleeve.

“When I finally left in 1916 they gave me a certificate. I tore that up. They gave me a Bible and a ten shilling note to face life at 16. I for one was never happier than the day I left her side in a gig for the last time.”

His account was endorsed by a former pupil from Helensburgh, who went aboard with his young brother in 1912 as they had nowhere else to go.

He said: “One morning ritual was climbing up one side of the rigging and then down the other — right over the top with an officer with a cane at your back and a belting for the last boy down.”

A former cook on the Empress recalled that the boys who helped her in the kitchen worked well and were a happy crowd — but they only had spoons to eat with, as knives and forks were not allowed in case they were used as weapons.

When the defaulters bugle was sounded the boys lined up for punishment. “I could hear the screams in the kitchen," the cook said. "Boys told me they were stripped and put over a cannon, then lashed. I certainly heard the cries.”

The other side of the coin is that in World War One Empress boys gained 14 commissions and won 37 decorations, including a D.S.O.

The other side of the coin is that in World War One Empress boys gained 14 commissions and won 37 decorations, including a D.S.O.

The Dumbarton Herald of 23rd February 23 1916 carried a story on MEDALS FOR “EMPRESS” BOYS. The report stated . . .

"Four members of HM Forces who received their early training in the Empress Training Ship, have been awarded naval or military honours.

"Petty Officer Albert Jarvie gained the Distinguised Service Medal, and Sergeant William Brown, 1st Gordons, was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. Bandsman J McArthur and Company Quartermaster-Sergeant A.G.Douglas have also received the DCM.

"Bandsman McArthur, 3rd HLI, joined the Empress in 1900 and was discharged four years later, joining the Army in 1907. For conspicuous bravery at Neuve Chapelle and at Ypres he was highly commended and for his devotion to the wounded under fire at Richebourg, where he was himself wounded, he received the DCM.

"Quartermaster-Sergeant Douglas, 2nd Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, received the DCM for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty on May 10th, 1915, at Hooge, when in temporary command of a company, all the officers of which had been killed or wounded.

"He successfully held his ground, although he knew the trenches on his left had been vacated. During this time he was exposed to a heavy enfilade and shell fire. On several occasions he gave a splendid example of courage and coolness to all under his command."

In 1917 John Lawson was awarded the Royal Humane Society's bronze medal for life-saving after he dived into the Clyde to rescue a comrade and non-swimmer, James Alexander, who had fallen from the ship's rigging into the water.

In 1920 Lady Geraldine Colquhoun of Luss boarded the Empress to present prizes, and a fascinating film of this can be seen here on the British Pathe website.

The following year eight boys passed the Board of Trade examinations in the use of the newly invented wireless. The Captain used to receive over 400 letters a year from old boys scattered all over the globe.

In all some 6,000 boys spent time on the Cumberland or the Empress, and 1,500 served in the armed forces in World War One.

There is a gravestone for the boys of the two vessels in Rhu Churchyard, next to that of Comet steamship pioneer Henry Bell.

The inscription reads: “The Cumberland Training Ship was moored off Rhu in 1869 and served as such until destroyed by fire but without loss of life on the early morning on 13 February 1889.

“The Cumberland was replaced by HMS Revenge which was renamed the Clyde Training Ship Empress and which continued to function successfully in this capacity until withdrawn by the Admiralty to be broken up in 1923. By that time there were only 149 boys aboard.

James Forrester 14th May 1870

James Forrester 14th May 1870There is a grave in Helensburgh Cemetery containing the bodies of 32 boys who died on board the Empress. Year after year small coffins were brought ashore, and often there was no family to mourn at the graveside.

Like the one in Rhu the marker on the communal grave, a tall granite stone, does not describe what they died of. Only the name and date of death is given, from 1879 to 1920.

- The photo of HMS Cumberland at the top of this article, one of only two known photographic images of the vessel, is published by courtesy of the Mitchell Library, Glasgow City Council, and is from the Wotherspoon Collection. For information about the library, visit http://www.glasgowlife.org.uk/libraries/the-mitchell-library/Pages/home.aspx. The other can be seen here.