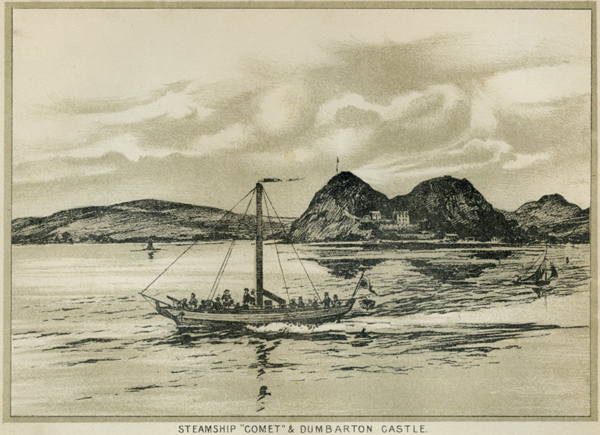

An excerpt from Annals of Garelochside, written by W.C.Maughan in 1897, from which the above sketch is taken.

Henry Bell may almost be said to rank with George Stephenson, as a discoverer of the great capabilities of steam, as a motive power, in propelling ships through the water.

He was born at the village of Torphichen, in Linlithgowshire, on 7th April, 1766, and was descended from a race of mechanics who, for generations, were known as practical mill wrights and builders, and had been engaged in many public works.

After being educated in the parish school, Henry Bell, in 1780, began to learn the trade of a stonemason.

Three years afterwards he became an apprentice to his uncle, who was a mill-wright, and on the termination of his agreement, he went to Borrowstounness to learn ship modelling.

In 1787 he worked with Mr James Inglis, engineer, with the view of completing his knowledge of mechanics.

From there he went to London, where he was employed by the celebrated Mr Rennie, and had opportunity of gaining a practical acquaintance with the higher branches of his art.

About the year 1790 he returned to Scotland, and is said to have set up as a house carpenter in Glasgow; his name appears, in October 1797, as a member of the Corporation of Wrights in that city.

He had ambitious designs in Glasgow, and strove to undertake public works but, from a deficiency of means, or from want of steady application, he never succeeded.

One who knew Bell at this time wrote thus of him: "The truth is, Bell had many of the features of the enthusiastic prospector; never calculated means to ends, or looked much farther than the first stages or movements of any scheme.

“His mind was a chaos of extraordinary projects, the most of which, from his want of accurate, scientific, calculation, he never could carry fully into practice.

“Owing to an imperfection in even his mechanical skill, he scarcely ever made one part of a model suit the rest, so that many designs, after a great deal of pains and expense, were successively abandoned. “He was, in short, the hero of a thousand blunders and one success."

The idea of propelling vessels by means of steam early took possession of Henry Bell, and ultimately he brought his ingenious scheme into practice.

Towards the close of last century, the Flyboats, as they were termed, formed the principal means of communication on the Clyde, between Glasgow and Greenock.

These boats were constructed by Mr William Nicol of Greenock, well known as an excellent builder of ships boats for many years. They were about 28 feet keel, about 8 feet beam, 8 tons burden, and wherry rigged.

A slight deck, or awning, was erected abaft the main-mast so as to cover in the passengers, who were accommodated on longitudinal benches.

Some of them, on a more improved principle, had a contrivance by which part of the deck or awning might be lifted up on hinges, to allow the passengers in fine weather more freedom in enjoying the voyage.

A kind of platform ran along the edge of the deck, outside, to allow those navigating the boat to pass from the bow to the stern, where the steersman sat, without troubling the passengers!

The boats generally left Greenock with a flowing tide if possible; if the wind was favourable, a passage of four or five hours to Glasgow was considered a great achievement.

When the wind and tide were adverse, then it was toilsome work, and the passengers and crew were glad to get out at Dunglas, and wait there for some hours, enjoying a ramble through the picturesque woods and crags in the neighbourhood.

These boats which, to the present generation, may well seem a slow and wearisome mode of progression, were still an improvement upon the packet boats, or wherries, in vogue till then.

One of the owners of the boats was Andrew Rennie, town drummer of Greenock, but a man of considerable ingenuity and speculation, and he proposed to his partners to have one built on a different model to be propelled by wheels.

Accordingly he got a boat constructed of a greater breadth of beam, to the sides of which he affixed two paddle wheels, to be worked by manual labour.

This boat, which came to be known as "Rennie's wheel boat", after making several trips to the Broomielaw, was sold, as it was not found to be any saving of labour to those who propelled it.

Henry Bell heard of this plan of the wheel on the boat's side, and applied to Mr Nicol to build for him a boat about 15 feet keel, with a well, or opening, in the "run", in which he placed a wheel, to be worked by manual-power.

Finding this single wheel not to answer the purpose intended, he got Mr Nicol to close up the well, and tried his boat with two wheels, one on each side.

He was convinced, after trial, that this was the true way of distributing the propelling power, though of course being wrought by manual labour no great speed could be attained.

Hence it was that, after long consideration, he came to the conclusion that, if he could apply steam power to his wheel, the deficiency in propelling power would be amply made up.

Another inventive genius, Symington of Greenock, had caused a canal boat to be fitted up with a steam engine, with a brick funnel, which was actually employed on the Forth and Clyde canal in towing vessels, but he did not succeed in adapting steam to the propulsion of boats in open waters.

Henry Bell now resolved to prosecute his steamboat scheme, and induced Messrs John & Charles Wood of Port Glasgow to lay down the keel of the first Steamboat in their building yard in October, 1811: this was the celebrated Comet, and she was launched in June, 1812, being called after the great meteor of the preceding year.

The Comet was a wooden boat of 42 feet long, 11 broad, and 5 deep, and 25 tons burden, and was fitted with the long funnel of the early steamers, which did duty for a mast as well.

John Robertson of Glasgow made the engine, which was a condensing one of 3 horse power, the crank working below the cylinder, the engine shaft of cast iron, a fly wheel being added to equalise the motion.

Originally the vessel was fitted with two pair of paddle wheels, 7 feet in diameter, with spur wheels 3 feet in diameter; so that by means of another spur wheel, placed between these, and geared into them, each pair of paddles rotated at the same speed.

However, this arrangement was found to be very inefficient, as one pair of paddles worked in the wash of the other, and there was a loss of power in working through toothed wheels.

Mr Robertson, the engineer, tried to dissuade Henry Bell from planning his paddles in this manner, but the latter insisted on trying the experiment, which was not successful.

The double wheels were then removed, and Robertson made another engine of 4 horse power, the cylinder 12 inches in diameter.

The workshop where this engine was made was in Dempster Street, North Frederick Street, Glasgow; it was a vertical engine.

The original model of the Comet is in the possession of Messrs. John Reid & Co. of Port Glasgow. The boiler of this historic vessel was made by David Napier of Camlachie.

Thus was the first steamboat completed, and it was announced in the Greenock Advertiser of 15th August, 1812, that the Comet would make the passage three times a week between Glasgow, Greenock, and Helensburgh, by the power of "wind, air, and steam."

The interest this created was widespread and intense, great crowds of people lined the shores from the Broomielaw downwards to witness her departure and arrival, but of those who gazed on the novel spectacle few realised to themselves the immense revolution which was thus being brought about in the annals of maritime enterprise.

Few believed in the ultimate success of the venture, and Bell was looked upon as an enthusiast, while many were even afraid to set foot in his vessel.

A traveller, in 1815, records that he sailed in the Comet from Glasgow to Greenock, leaving in the morning, and arriving at Greenock after seven hours passage, three of which, however, had been spent lying on a sandbank at Erskine.

Soon after the success of Henry Bell's steamer, the next vessel worked by this novel power was the Elizabeth, of 33 tons burden, 58 feet long, and she also was built by John Wood.

But so little apprehension was caused by the advent of the steamboats that wherries were regularly announced to sail from Greenock to Helensburgh and the Gareloch in opposition to the steamers.

It was years before this successful effort at steam navigation that Bell conceived the idea of propelling vessels by other agency than the power of wind.

He thus wrote in 1800, "I applied to Lord Melville on purpose to show his lordship and other members of the Admiralty, the practicability and great utility of applying steam to the propelling of vessels against winds and tides, and every obstruction on rivers and seas where there was depth of water."

Disappointed in this application he repeated the attempt in 1803, with the same result, notwithstanding the emphatic declaration of Lord Nelson, who, addressing their lordships on the occasion, said, "My Lords, if you do not adopt Mr. Bell's scheme other nations will, and in the end vex every vein of this empire. It will succeed, and you should encourage Mr Bell."

Failing in this country, Bell tried to induce the naval authorities in Europe as well as the United States government to adopt his plan; he succeeded with the Americans, who were the first to put his scheme into practice, and were followed by other nations.

After his great achievement in successfully navigating the waters of the Clyde by the power of steam, Bell, who had settled in Helensburgh, continued to prosecute his business of builder and wright.

He also embarked upon more speculations in connection with efforts to establish other passenger steamers, but did not make any great success, for he was ever possessed by a restless desire to try new experiments.

He originated various improvements in Helensburgh, of which town he was the first Provost, serving from 1807 till 1810. Latterly he had the management of the Baths Hotel, assisted by his industrious wife, and there he died in November 1830.

Efforts were made by his friends to induce the government to award a sum of money to one who had done so much to open up the way to our vast international carrying trade, and whose genius had paved the road for an entire revolution in the navigation of the ocean.

But all they could succeed in getting was a paltry dole of £200, as will be seen from the following pathetic letter, written to one who had interested himself in the matter:

"Baths, Helensburgh, 19th June, 1829. My Dear Friend, — I write these few lines lying on my bed unable to sit up. But the letter you sent me with the remittance of £200 from the Treasury, a gift ordered by the late Mr Canning, will relieve my mind a little, and enable me to get Mrs Bell's house finished, and to pay the tradesmen.

“I was afraid I should not have got this £200, little as it is. The wounds in my legs are rather easier during the last few days, owing to my keeping close to my bed. I will write to you in a day or two more fully,

"I am, your old friend, HENRY BELL.

"Mr E.Morris, London."

For a few years he had enjoyed a pension of £100 a year from the Clyde Trust, for although he had been the pioneer of vast improvements to navigation and commerce, he had reaped none of the rewards of his inventive genius.

His funeral took place on the 19th November, when a large company of mourners followed the body of the man who had done so much for steam navigation to its last resting place in the churchyard of Row.

In 1839 a stone obelisk in memory of Henry Bell was erected on the highest point of the rock, beside the old castle of Dunglass, just overlooking the scene where his first triumph was gained.

The late Robert Napier of Shandon, who knew well how much his friend Henry Bell had laboured for the triumph of steam navigation, placed a fine sitting statue of him in Row Churchyard.

The late Robert Napier of Shandon, who knew well how much his friend Henry Bell had laboured for the triumph of steam navigation, placed a fine sitting statue of him in Row Churchyard.

The expression of the face is well rendered, and gives a good idea of the man, as he was in his later years, which were much clouded with disappointment.

A very handsome granite obelisk in memory of Bell also stands in a conspicuous position on the sea esplanade at the foot of James Street, Helensburgh, chiefly erected through the public spirit of the late Sir James Colquhoun and Robert Napier.

On the pedestal is the following inscription:— Erected in 1872 to the memory of HENRY BELL, THE FIRST IN GREAT BRITAIN WHO WAS SUCCESSFUL IN PRACTICALLY APPLYING STEAM Power for the purposes of navigation. Born in the county of Linlithgow in 1766. Died at Helensburgh 1830.

For some years the Comet continued to ply on her original route, and also for a short period on the Firth of Forth, and subsequently she traded between Glasgow and Fort William, via the Crinan Canal.

On the 7th of December, 1820, she started on her return journey, but on the 12th, at Salachan, the vessel struck on a rock, and had to be beached to enable the necessary repairs to be made.

On the 14th the run to Glasgow was resumed, and on the 15th was at Oban, although by that time water was beginning to enter the vessel.

On that day the Comet left Oban for Crinan, during a violent snowstorm, and shortly afterwards was driven, near the Dorus Mohr, by the force of the waves and wind on to the rugged point of Craignish, where she parted in two, amidships, at the exact spot where she had been lengthened in 1818.

Henry Bell, the owner of the Comet was on board, but he, along with all the crew and passengers, were safely landed.

After the unhappy striking of the vessel the after part drifted out to sea, and the forward part sunk in deep water.

The engines, however, were saved, and incorporated in the machinery of the second Comet of 94 tons, built by James Lang of the Dockyard, Dunbarton, in 1821, which had one engine of 25 horse power.

This vessel also was lost off Kempoch Point, Gourock, on 21st October, 1825, by coming into a collision with a steamer, the Ayr, when a lamentable loss of life occurred.

Such was the fate of the little vessel whose success inaugurated a new era in our mercantile marine, with results of wonderful magnitude to all the nations of the world.

It is melancholy to reflect how little was done to smooth the closing years of the man to whose ingenuity and perseverance so much of the triumph of steam navigation was due.

With almost prophetic foresight Henry Bell thus spoke in 1812, when the little Comet first sailed on the Clyde:

"Wherever there is a river of four feet in depth of water through the world, there will speedily be a steamboat. They will go over the seas to Egypt, to India, to China, to America, Canada, Australia, everywhere, and they will never be forgotten among the nations."

No doubt there were not wanting those who sought to take away from Bell the distinction of having been the first to apply steam to the propelling of vessels, and Fulton, the American, has claimed the honour.

Dr Cleland, the Annalist of Glasgow, writes on this subject:

"It was not, however, till the beginning of 1812 that steam was successfully applied to vessels in Europe, as an auxiliary to trade.

“At that period, Mr Henry Bell, an ingenious, self-taught engineer, and citizen of Glasgow, fitted up, or it may be said without the hazard of impropriety, invented the steam-propelling system, and applied it to his boat the Comet, for, as yet, he knew nothing of the principles which must have been so successfully followed out by Mr Fulton."

Morris, the friend of Henry Bell, who wrote the only life of the inventor which has ever been published, a brief and unassuming memoir, gives the following memorandum regarding Bell's claims to be the first who introduced steam power, which was drawn up by some of the early Clyde engineers.

"Glasgow, 2nd April, 1825.

"We, the undersigned engineers in Glasgow, having been employed for some time past in making machines for steam vessels on the Clyde, certify that the principles of the machinery and paddles used by Henry Bell in his steamboat the Comet, in 1812, have undergone little or no alteration, notwithstanding several attempts of ingenious persons to improve them.

“Signed by Hugh and Robert Baird, John Neilson, David and Robert Napier, David McArthur, Claud Girdwood & Co., Murdoch & Cross, William McAndrew, William Watson."

The following appreciative sketch of Henry Bell appeared in the modest Helensburgh Guide, originally published by the late Mr William Battrum more than thirty years ago, and now out of print:

The following appreciative sketch of Henry Bell appeared in the modest Helensburgh Guide, originally published by the late Mr William Battrum more than thirty years ago, and now out of print:

"In person Mr Bell was about middle size, a stout built fresh complexioned man, hearty and genial in his manner. His features were regular and expressive, impressing a stranger at a glance with a good opinion of him as a shrewd, pawky Scot, an impression which ten minutes conversation stamped as sound.

“His general knowledge was extensive, and he had a peculiar aptitude for seizing the salient points of any new invention, and making himself master of the subject.

“He was a great talker, when excited by any favourite hobby, and nothing delighted him more than an intelligent listener, to whom he would descant all night on any of his multifarious plans and schemes.

“There were always some leading projects in view. The construction of a canal betwixt east and west Tarbet, in Lochfine, was a favourite one.

“He had also a scheme for the partial drainage of Loch Lomond, and reclamation of the land, about which he had an extensive correspondence with the Duke of Montrose, who did not receive it favourably.

“The introduction of water to Helensburgh from Glenfruin, he had also in view. The reclamation of waste lands in Scotland, and even the Suez Canal he discussed, and urged its practicability, despite the opinion of many eminent engineers.

“Of all his plans he was exceedingly sanguine; neither the indifference of others, the want of resources, partial failure, or any of the thousand embarrassments that haunt projectors, daunted him.

“Whatever the failure or disappointment met, he was always hopeful of ultimate success. With a large measure of Watt's inventive faculty, he possessed in a good degree the energy and knowledge of men which Watt's partner, Boulton, enjoyed.

“To the many doubts and disbelief of scientific and unscientific men that steam vessels would never accomplish much, Bell's reply was always, 'they will yet traverse the ocean’, and his prophecy, now being fulfilled, living men who heard it will verify."