MEMORIES of the night Cardross was bombed when she was ten years-old are still fresh for a villager who now lives in America.

Patricia Lockhart, now Mrs McInnis, left Scotland for Canada in 1956, and has lived in San Diego, California, since 1960.

Helensburgh Heritage Trust

Helensburgh Heritage Trust

Helensburgh Heritage Trust

Helensburgh Heritage Trust

MEMORIES of the night Cardross was bombed when she was ten years-old are still fresh for a villager who now lives in America.

Patricia Lockhart, now Mrs McInnis, left Scotland for Canada in 1956, and has lived in San Diego, California, since 1960.

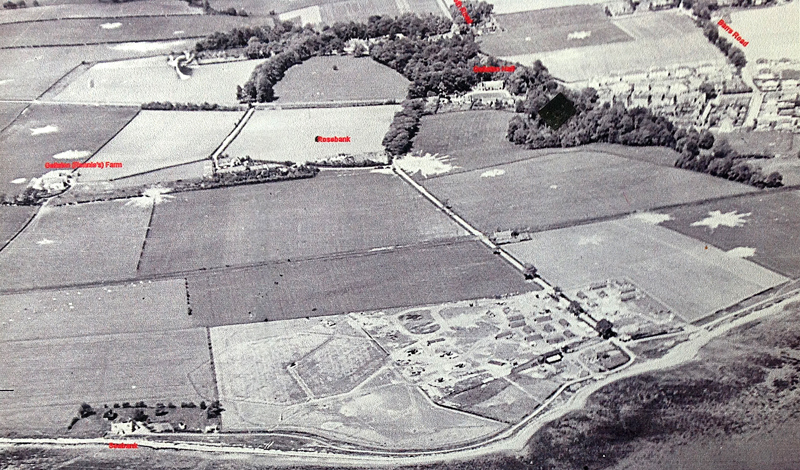

IT HAS always been something of a puzzle why Cardross, a small harmless village, should so incur the wrath of the mighty Luftwaffe over the night of May 5 1941.

Could the World War Two bombing of the village have happened because of mistaken identity?

A CARDROSS army officer with a shipbuilding background died instantly when he was hit by a shell on the Belgian Western Front in during World War One.

A CARDROSS army officer with a shipbuilding background died instantly when he was hit by a shell on the Belgian Western Front in during World War One.

Captain William Beardmore Stewart, of Auchenfroe in the village, was killed in action on May 24 1917 at the age of 33, and is buried at Reninghelst New Military Cemetery near Ypres.

ONE of the best known Helensburgh men to die in action on the front in the first two years of World War One was a 39 year-old with twenty years service.

ONE of the best known Helensburgh men to die in action on the front in the first two years of World War One was a 39 year-old with twenty years service.

Lieutenant James Francis Marsland MC, known to his friends as Jim, was serving with ‘C’ Company of the 2nd Battalion (109th Foot) the Leinster Regiment (Prince of Wales’s Royal Canadians).

A YOUNG Cardross man who volunteered twice in World War One lost his life shortly after entering a trench with his platoon.

A YOUNG Cardross man who volunteered twice in World War One lost his life shortly after entering a trench with his platoon.

Second Lieutenant Frank Ritchie was killed in action near the village of Givenchy in Pas-de-Calais on May 25 1915 at the age of 22.

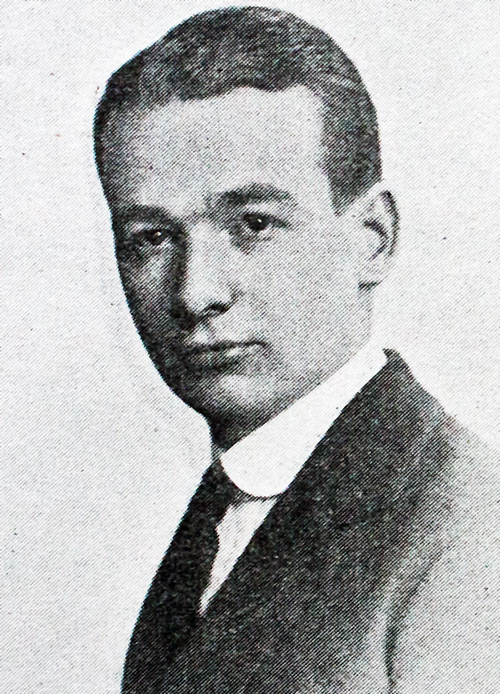

A PUPIL at the then St Bride’s School in Helensburgh — now Lomond School — became an intelligence officer and played an important part in the battle against German U-boats in the Second World War.

Caroline Chojecki MBE, who died on September 24 2017 aged 96, was born Caroline Elizabeth Rowett on November 11 1920, to John Quiller Rowett and his wife Helen, nee Coats, one of three children.

A PHOTO of a military man found in a shop in Inverness in 2012 sparked a search which led to Helensburgh — and to a tragic First World War tale.

A PHOTO of a military man found in a shop in Inverness in 2012 sparked a search which led to Helensburgh — and to a tragic First World War tale.

Now the same man is featuring again in a new search for information.

RESEARCHING an act of generosity produced a fascinating link to Helensburgh’s past.

RESEARCHING an act of generosity produced a fascinating link to Helensburgh’s past.

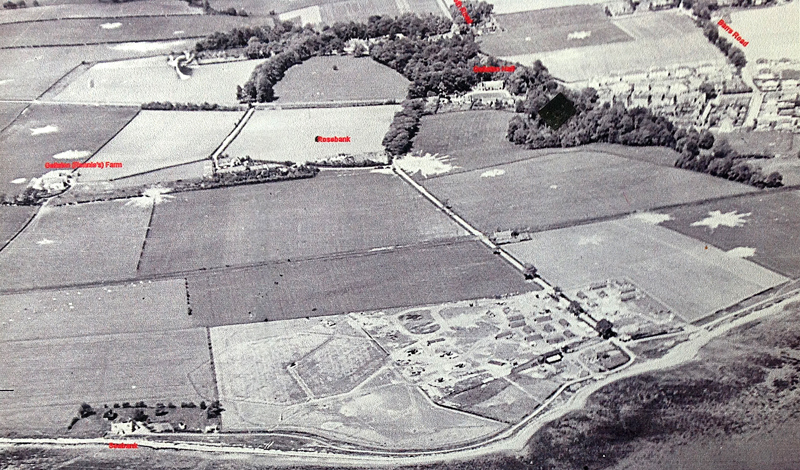

A HELENSBURGH man was a World War One flying ace with six aerial victories before his death in action.

A HELENSBURGH man was a World War One flying ace with six aerial victories before his death in action.

Although born in Grangemouth on October 15 1892, Captain David Sidney Hall MC was the son of Helensburgh master grocer and later laundry proprietor William Hall and his wife Annie, nee Fleming, who married at Whiteinch on July 16 1880 and lived at Birkfell, 30 Charlotte Street.

A WELL-KNOWN Rosneath Peninsula man played an important role in the discovery of a sunk submarine in 1951 because of his involvement with the development of underwater television.

A WELL-KNOWN Rosneath Peninsula man played an important role in the discovery of a sunk submarine in 1951 because of his involvement with the development of underwater television.

Former Kilcreggan Primary School and Hermitage School pupil John Revie — known to all as Jack — took part in finding the wreck of HMS Affray, a submarine which mysteriously sank with all hands off the Channel Islands.

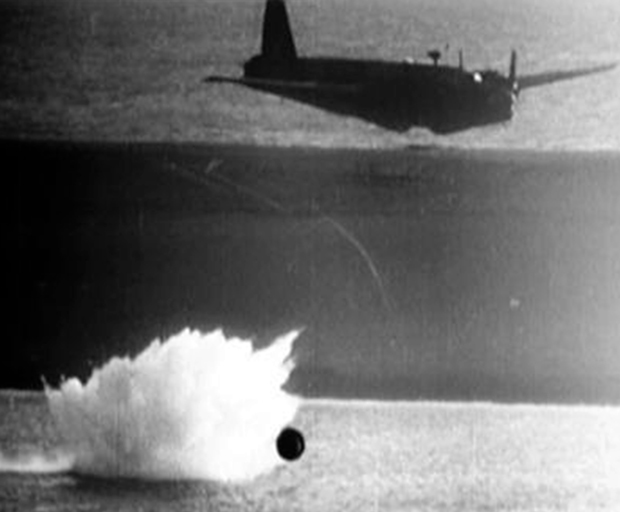

THE RAISING from Loch Striven of three Highball bombs — tested by the Rhu-based Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment — hit the headlines in July 2017.

It happened around the time of the unveiling of a memorial stone at Kidston Park to commemorate the war time activities at RAF Helensburgh, home of the MAEE.

FORMER ‘Wrens’ in Helensburgh and district celebrated the centenary of the Women’s Royal Naval Service in 2017.

FORMER ‘Wrens’ in Helensburgh and district celebrated the centenary of the Women’s Royal Naval Service in 2017.

They include people like Bletchley code breaker Mrs Betty Balfour, who signed up to the Wrens at the age of 17, and a former Helensburgh Citizen of the Year, Mrs Jean Holland.

The WRNS — popularly and officially known as the Wrens — was the women’s branch of the Royal Navy.

First formed in 1917 for the First World War, it was disbanded in 1919, then revived in 1939 at the beginning of the Second World War, remaining active until integrated into the Royal Navy in 1993.

Their jobs included cooks, clerks, wireless telegraphists, radar plotters, weapons analysts, range assessors, electricians and air mechanics.

On October 10 1918, 19 year-old Josephine Carr from Cork became the first Wren to die on active service, when her ship RMS Leinster was torpedoed.

By the end of the war the service had 5,500 members, 500 of them officers.

By the end of the war the service had 5,500 members, 500 of them officers.

In addition, about 2,000 members of the WRAF had previously served with the WRNS supporting the Royal Naval Air Service and were transferred on the creation of the Royal Air Force.

The Wrens were disbanded in 1919, but revived in 1939 at the beginning of the Second World War, with an expanded list of allowable activities, including flying transport planes.

At its peak in 1944 there were 75,000 Wrens, but during the war there were 100 deaths.

One of the slogans used in recruiting posters was “Join the Wrens — free a man for the fleet.”

It remained in existence after the war and was finally integrated into the regular Royal Navy in 1993 when women were allowed to serve on board navy vessels as full members of the crew.

In October 1990, during the Gulf War, HMS Brilliant allowed the first women to serve officially on an operational warship.

Female sailors are still known by the nicknames Wrens — or Jennies (Jenny Wrens) in naval slang.

The celebrations to mark the centenary began on Wednesday March 8, when the National Museum of the Royal Navy in Portsmouth formally opened an exhibition entitled ‘Women and the Navy’ which runs until November.

The main aims of the centenary organisers are to celebrate the formation of the WRNS and its subsequent history, to recognise the continuing role of women in the Royal Navy today, and to publicise the work of the WRNS Benevolent Trust and the Association of Wrens.

A Scottish celebration dinner on board the Royal Yacht Britannia at Leith in November is already sold out, and there will be a church service in Edinburgh on Sunday November 26.

Betty Balfour, who celebrated her 90th birthday on September 11 2016, attended the Government Code and Cipher School before being stationed at Bletchley Park, Milton Keynes facility — home of the Enigma machine.

Betty Balfour, who celebrated her 90th birthday on September 11 2016, attended the Government Code and Cipher School before being stationed at Bletchley Park, Milton Keynes facility — home of the Enigma machine.

Like thousands after World War Two, Betty slipped back into everyday life, never speaking of her experiences as a code breaker – including a never-heard-before alternative use for the Enigma machine – and her service remained unknown to those closest to her.

“My parents died without ever knowing what I did,” she said. “We never spoke of it — we signed the Official Secrets Act and took it very seriously.

“We stayed about an hour from Bletchley Park and we moved around all the time between different accommodation so that if one place was bombed we wouldn’t all die.

“We knew we were expendable, but it was what was in our heads that was important.”

It is only today that the extent of the role of the codebreakers in the Second World War is known, and although they are now hailed as hidden heroes, Betty said the day-to-day work was boring.

During ten-hour shifts underground, the Enigma machine would produce reams of paper and Betty would sit at one of the long tables and decipher Japanese code.

“I also remember that we had to divide everything into five,” she said. “It was appalling, boring work, but it was most important.”

She recalled that the Enigma also had another great but less publicised use. “When the girls were on the nightshift we used to hang our smalls from the Enigma because it was a great way to dry them,” she said.

“It used to be festooned with bras and pants all through our night duty. Back then it must have looked a real sight.

“You made the most of the little things, like a lunch break, and to me it was all real life. It was obscure, very demanding, and eye straining work, but in the end I supposed it saved the war.”

Jean Holland, who lives in Waverley Court, West King Street, was the first ever winner of the Helensburgh Garelochside Rotary Club/Helensburgh Advertiser Citizen of the Year award in 1998.

Jean Holland, who lives in Waverley Court, West King Street, was the first ever winner of the Helensburgh Garelochside Rotary Club/Helensburgh Advertiser Citizen of the Year award in 1998.

The biennial awards are presented to individuals, who have made a significant contribution, recently, or over a period of time, to the benefit of the community.

Jean was nominated for the award by Margaret MacInnes, of the Margaret Rose School of Dance, for her work with the senior citizen clubs in the town.

From the 1980s, Jean played a key role in organising events, such as trips to the theatre, for a number of senior groups and clubs in Helensburgh.

Now in her mid-nineties, she still treasures the large silver quaich she received.

In 2012 she was named as a Timebank Hero in the Argyll Communities Volunteer of the Year Awards, which recognise the unsung heroes who through timebank are supporting others in the community and who, through the system of time credits, give freely of their time and talents to help others.

The citation read: “Jean has been a ‘timebanker’ for three years and, at 89 seems incapable of running out of enthusiasm or ideas which support her community and others.

“For many years she would be found organising community social events, and is a regular visitor to AVA Helensburgh office. She earns time credits through Helensburgh Carers, the Seniors forum and local Lunch club amongst others.

“She is also one of the founder members of Helensburgh Grey Matters – the forum and activity resource supported through the Reshaping Care programme.

“Timebank is reciprocal, based on co-production, and in turn Jean has had help with freeview installation, minor repairs and has joined outings and social events. She is a great advocate of the Reshaping Care programme and the potential within it.”

While not as mobile as she used to be, the cancer survivor is still very active.

Originally from Springburn, Glasgow, the then Jean Scoughley was working in the accountants office in William Collins Publishers in the city during World War Two when she decided to become a Wren.

“I joined in March 1944, and went to college in London,” she said. “Then I got my posting to HMS Beaver which was at Grimsby, a minesweeper base.

“I’d only been there a month, but I was homesick so I went in and asked for a compassionate posting back to Scotland.

“But by the time it came through, we were having a ball as all round us were RAF stations and American stations. We were invited to all sorts of social events.

“It must have been terrible for the Wrens in London when the buzz bombs came over, but it was nice for us when we were in Grimsby. We never really saw much activity I suppose.

“The minesweepers were out and in all the time, but Grimsby was a rare place. It’s so nice, and the local people were really kind to us all.

“After about ten months I got my posting back to Scotland — to Largs, believe it or not. By then I did not want to go!

“After about ten months I got my posting back to Scotland — to Largs, believe it or not. By then I did not want to go!

“A Wrens unit — they called it a ship — was evacuated with 200 Wrens, mostly local to London, up to Largs for safety.

“At that time if you deserted from the Wrens there must have been some sort of punishment, but you were not put in jail or anything — so some of them were deserting and going back to London.

“I was posted to HMS Copra at Largs and that’s where I ended my Wren days in 1946. I worked in the Pay Office working on pay for men in the ships which were going to or were already out in Japan.

“We very rarely saw anybody apart from other Wrens. There were about 200 in that big office. We slept at Skelmorlie Hydro and they bussed us into Largs to The Mooring, which was the office.

“I did enjoy my life in Grimsby more than Largs. I made loads of civilian friends there, but when I came back up here my friends were either married or were in other services and I had not much company at all.

“You can imagine what it was like when we were there with 200 Wrens. Trying to get a dancing partner at a dance was heavy going right enough.

“But life in the Wrens was really good — I enjoyed it, and I am glad that I still have souvenirs of those days.”

After being demobbed in 1946 Jean returned to Springburn, and in September of that year she got married.

“I think it was about 1951, when my husband was in the Air Force Reserves and I was not seeing much of him at weekends that I just decided to join the Wrens Reserves,” she said.

“That was at Whitefield Road in Govan, but I was only there for two years and I became pregnant with my son, who has since died.”

She and her husband came to Helensburgh in 1976.

“We had a holiday house here and I used to come down and really enjoyed Helensburgh. So we decided to move here, and I have been here ever since,” she said.

The late Marion Reilly, nee Glennie, who died in September 2016, treasured memories of her wartime work on degaussing at Helensburgh pier, through which she met the man who was to become her husband.

The late Marion Reilly, nee Glennie, who died in September 2016, treasured memories of her wartime work on degaussing at Helensburgh pier, through which she met the man who was to become her husband.

Her story appeared in her book ‘A Link in the Chain’ which she published privately. Marion was born in Blairgowrie, Perthshire, but the family then moved to Helensburgh.

Degaussing is a process in which systems of electrical cables are installed around the circumference of ship’s hull, running from bow to stern on both sides. A measured electrical current is passed through these cables to cancel out the ship’s magnetic field.

Degaussing equipment was installed in the hull of Navy ships and could be turned on whenever the ship was in waters that might contain magnetic mines, usually shallow waters in combat areas.

Marion wrote: “At the beginning of September 1939, I found myself unemployed. Our neighbour and good friend, who was the Town Clerk, knew me well, and when approached by the Naval Authorities who wanted to enlist some local girls as Wrens, he put forward my name.

“A WRNS officer knocked at our door one day in December and offered me a post as a technical Wren. She described the job as photographic work, but it was in the degaussing department of the Admiralty, and involved working on the pier.

“The headquarters of the Degaussing Organisation were in Portsmouth, but the first degaussing range with undersea cables was set up on the Clyde off Helensburgh, with our headquarters on the pier.

“We were a small team with two naval officers, a physicist, five Wrens, a motor boat and crew, and a Morse code signaller.

“We were a small team with two naval officers, a physicist, five Wrens, a motor boat and crew, and a Morse code signaller.

“My companion Wrens were 18 year-olds, all fresh from boarding schools, and I had never had any office training, so we were a very naive and helpless bunch at first.

“We had no idea what was expected from us, but eventually it all began to run smoothly, working on shifts to cover the tidal movements and the arrival and departure of ships.

“At 25 I was older than the other Wrens, so I was given a stripe and promoted to Leading Wren.

“We worked hard but it was an enjoyable time, though marred by sad news of battleships sunk and many merchant ships torpedoed.”

The late Patricia B.Farley from Manchester wrote ‘Birds of a Feather: A Wren’s Memoirs, 1942-1945’ and told of her life as a Wren at Portkil, Kilcreggan, where she too was involved in degaussing.

Her degaussing inspection station was an old concrete fort from World War One, opposite to Greenock and Gourock — very busy ports that handled many vessels, merchant and military.

She wrote: “It was here that I received my indoctrination into degaussing operations. The Fort, as it was always called, was a stone’s throw from the Barn where we lived, and we passed a full workday there, six days a week.

“If we had an early call for a ship, we would be there and, in the summer months when it stayed light until almost 11.30pm, we could be working after 9 or 10pm.

“There was deep water close offshore to our offices, deep enough for the biggest aircraft carriers and warships to make several runs through a selected passage, marked by buoys, while taking the degaussing tests.

“Special underground cables ran from that area up into one of the buildings, where the information was processed in a temperature controlled room furnished with camera equipment. The data would emerge on to heavy photographic paper, encased in rolls located in a row of machines.

“Special underground cables ran from that area up into one of the buildings, where the information was processed in a temperature controlled room furnished with camera equipment. The data would emerge on to heavy photographic paper, encased in rolls located in a row of machines.

“Our job was to wait for the data to appear, rip it off the machines, and take it into the darkroom. There we would develop the photographs in a hydrochloric solution.

“In the summer, we ‘Barnites’ often went swimming off the jetty, but it wasn’t recommended too highly because the water was greasy from so much ship oil.

“We were never allowed to tell anyone what our job was in the Wrens. When I signed on, it had been made implicit that the work was secret, and the less said the better.”

Another Wren, Louisa Jenkins from Edinburgh, a signaller, told her story in ‘Bellbottoms and Blackouts: Memories of a Wren’.

Her final base was HMS Rosneath, a demobbing station where naval servicemen were sent before being honourably discharged, and her accommodation was at Rosneath Castle.

She wrote: “Since the end of the war the base had been steadily getting quieter and the Wrens were becoming bored. Mostly the signals were concerned with the incoming and outgoing of the matelots and officers in the various stages of demobilisation.”

She did enjoy the Christmas Eve 1945 Carol Service in St Modan’s Church.

“This was a joyous occasion,” she wrote, “as hostilities were at an end, peace was with them again, and she would soon be home for good.

“Yes, although she had been looking forward to being released to Civvy Street, she would sorely miss the camaraderie of the friends she had met in the service.”

Morag Cook said that her mother, maiden name Doreen MacNab, nee Reid, served as a Wren at Rosneath Castle.

Morag Cook said that her mother, maiden name Doreen MacNab, nee Reid, served as a Wren at Rosneath Castle.

“Mum will be 95 this June and whilst she is quite frail of mind nowadays she can still recall with pride being a Wren,” she said.

“Mum was originally born in Enfield and was at Hornsby Art College when World War Two broke out.

“The art college was bombed and closed, and after a period of conscription in a factory making aircraft instruments, then another in the Land Army, mum applied to join the Royal Navy.

“She was posted to Rosneath Castle and worked in the captain’s office.

"It was while she was there, at the end of the war, mum had a day off and went with a Wren friend — who I think was Betty Needham — to visit a lady in Portincaple who did teas and scones.

“That lady was Robina MacNab, affectionately known as Beanie. She had a nephew Duncan MacNab, my father.

“That lady was Robina MacNab, affectionately known as Beanie. She had a nephew Duncan MacNab, my father.

“Duncan had also joined the Royal Navy for the war and was home visiting his parents Lizzie and Dougie in Portincaple when mum met him. Just one of the many love stories the war made happen!

“My mum never left Portincaple, bringing up two daughters, Fiona and then myself, Morag.

"Dad sadly died young at only 55 and mum continued on, only leaving Portincaple when it became too much for her to live there alone.”

The story of another Helensburgh Wren, Agnes McGee, who also worked in code breaking, is told here.

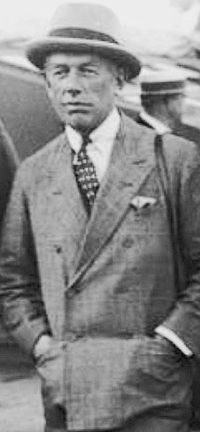

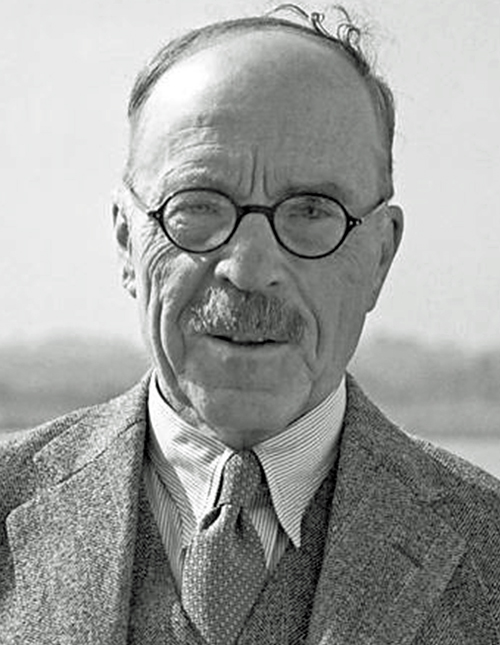

A VISIT to the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment at RAF Helensburgh in 1940 by Sir Henry Tizard was a prelude to what is said by historians to be the most important secret mission of World War Two

A VISIT to the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment at RAF Helensburgh in 1940 by Sir Henry Tizard was a prelude to what is said by historians to be the most important secret mission of World War Two

A team of six headed by Sir Henry went to America with a black box of secrets. With him were two of the world’s experts in radar, Dr Robert Watson-Watt and 24 year-old genius Edward Taffy Bowen.