A HELENSBURGH man suffered the ordeal of being torpedoed and spending almost a fortnight in a lifeboat during World War Two.

Charles McKechnie, who lived in Sinclair Street, survived to tell the tale, and it was printed in an emotional article in the Helensburgh and Gareloch Times.

Unlike World War One, when information about the war and service personnel was readily available, very little was reported in World War Two — ‘there’s a war on’, and secrecy ruled.

Perhaps that is why the local paper went into such detail and considerable outspoken comment in its article about the burgh man.

It was headlined ‘Helensburgh man torpedoed in mid-Atlantic’, and here it is in full . . .

Stories of those at sea who have endured agonising days and nights at the mercy of the elements in overloaded or tragically disburdened lifeboats and rafts are sadly frequent.

These experiences are imminent for those who live their lives in ships.

A colossal war, in which the mad lust and felonious intent of the malignant Nazi-Fascist-Japanese combine has obviously been the obliteration of every race which would impede its Satanic progress, portends many a cruise of death, alike for hospital ship and refugee transport.

The instinct of the ravenous beast is to bury his fangs deep into the flesh of his helpless victim, so the barbarian — the ‘Hun’ — only knows his own savage, rapacious desire.

He knows no sorrow but defeat! The doctrine of Diabology holds full relentless sway in an era of fiendish conflict. Wily sycophants crop up like fungus — renegades, in the fat pay of a cruel, unscrupulous foe, to direct him to his gruesome spoil.

The resultant aftermath will be largely dependent on the measure with which all that is rank and vile is exterminated from human minds and the extent to which goodness and right thinking is universally sown.

Charles McKechnie is home after being torpedoed in mid-Atlantic, to add but one more to the many countless experiences which when fully recorded will form a great world epic of courage and endurance. He has been twelve years in the Merchant Navy, and he was in India actually at the outbreak of war.

An Army pensioner from the last war, he felt impelled to do his patriotic ‘bit’ once more, so instead of coming home he remained afloat.

When coming home on leave his boat was attacked on the evening of November 6 1942.

Most of the lifeboats were lowered and clear of the listing ship before she received her last shattering blow and floundered to her doom beneath the lucent, uncanny deep abyssal oceanic gloom.

She went down in four minutes in a shuddering suction dive. His particular lifeboat picked up fourteen survivors including the captain and the purser.

All night long they kept sailing around, picking up survivors till well on after the sun was up.

A U-Boat came alongside the same day, and at first they thought he intended to shell them. However their fears were soon at rest.

He proved a decent sort of enemy, and after enquiring who they were, where they were bound for, the nature of their cargo, and whether they had been carrying any prisoners of war, he gave them their location — 1,000 miles distant from Walrus Bay, 1,000 miles from Trinidad, and 500 from St Helena.

They set course for the isle of Napoleon’s dramatic banishment, and they sailed for two days in tranquil waters of blue transparency.

For a couple of days and nights the six lifeboats managed to keep together. Each night they were all securely lugged together with hawsers till the following morning.

A storm blew up on the third day, and in the teeth of the gales they lost sight of their companion craft with the exception of that manned by the second officer.

His was the only boat with a sextant — the others had been blown out by the torpedo blast.

The daily rations were half a dipper of water in the morning, and at night two Horlicks tablets, a piece of chocolate, and half a biscuit with a teaspoonful of pemmican.

Thirteen days elapsed before they sighted land on the morning of November 19, during which time they saw neither mast nor aircraft.

On the fourteenth they were picked up by a ship and taken to Jamestown, St Helena. Mr McKechnie gives great credit to the captain and the second officer for their skilful manipulation of their lifeboats.

Tales of such isolation adrift for weeks in open submerged boats and rafts are frequent.

Scantily clad men, women and children, at the mercy of mountainous seas and penetrating blast or exposed to fervid heat and parched with thirst in shark-infested seas are horrors to which we have become too painfully familiar.

It is impossible for any, except those who have come through such ordeals, to even faintly visualise the extent of their sufferings. Such experiences, like all anguish, cut into human consciousness, making deep, indelible impress.

To those who emerge unscathed, unimpaired, strength is born of much suffering, sympathy and understanding.

If, then, wisdom is born, who but a barbarian would not welcome such a glorious birth.

The wounds of prolonged buffeting may temporarily cripple the winged flight, but, like an exhausted bird, the spirit of man soars up again and o’er the raging tempest far below, imperturbable, imperishable.

Travellers, adventurers, explorers, mountaineers and navigators have, down the ages, endured much in their quest for knowledge or wanderlust.

The sufferings endured by those in mortal combat, when wounded, dying, the heroism of those killed in battles in air or land or sea, ranks with the same selfless devotion shown in the immortal annals of history.

The people of St Helena were most hospitable and kind to their weary, rescued guests.

The shipwrecked mariners presented a wireless set to the hospital before they took their departure once more for ‘Blighty’, as a token of their exceeding great gratitude.

A plate was inscribed and placed on the old castle walls, home of the exiled Napoleon, as a memento of their sojourn.

The voyage home from St Helena was accomplished without mishap, but to folks who have recently endured the shock of murderous, oceanic catapult and been stranded in submarine infested waters, a second voyage must be fraught with severe nervous ordeal not without portent.

The Allied ‘Combined Operations’ is a saga which with the advent of peace will ring down the years as an historic record and emblem of human endurance.

I have not been able to find out any more about Charles McKechnie, but I was able to establish more details about what happened.

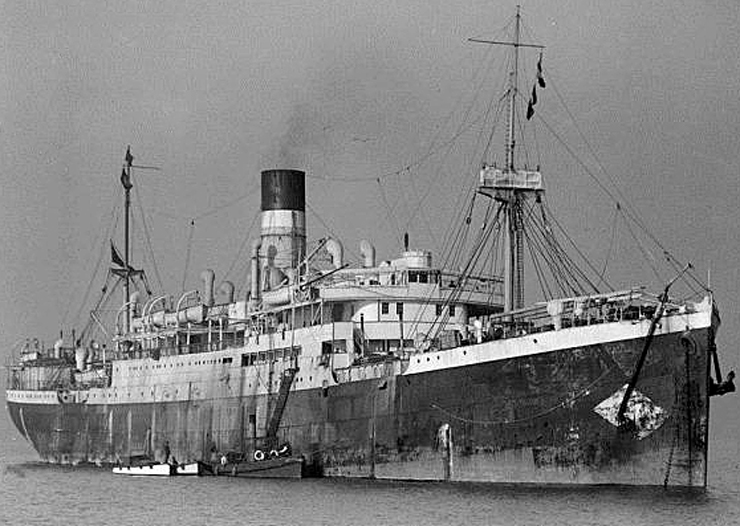

He was aboard the 8,000-ton Ellerman Lines passenger ship City of Cairo, which was sunk by U-68. There were 207 survivors but 104 dead.

The ship, with a cargo of 7,422 tons of general cargo, including pig iron, timber, wool, cotton, manganese ore and 2,000 boxes of silver coins, left Bombay on October 1.

On November 1 the City of Cairo left Capetown with 150 passengers, of whom nearly a third were women and children, and followed the African coast until she reached a longitude of 23°30S, where the vessel turned westward across the South Atlantic.

She was unescorted, only capable of 12 knots, and her engines burned smokily.

On November 6, the smoke trail was sighted by U-68, captained by Karl-Friedrich Merten, and at 21.36 hours he fired one torpedo which struck the vessel.

The captain, William A. Rogerson, gave the order to abandon ship and all the women and children were able to leave the ship safely. Only six people were lost in the evacuation.

The captain, William A. Rogerson, gave the order to abandon ship and all the women and children were able to leave the ship safely. Only six people were lost in the evacuation.

Merten fired a second torpedo after 20 minutes, which caused the ship to sink by the stern about 450 miles south of St Helena. Then U-68 questioned the survivors in the six overcrowded lifeboats and left the area.

The survivors were over 1,000 miles from the African coast, and twice as far from South America. Because of their limited supplies, they set sail for the historic island of St Helena.

The survivors calculated that they should reach St Helena in two to three weeks and rationed the drinking water accordingly. Everyone was limited to just 0.11 litres a day, even though they were exposed to tropical heat.

Pemmican consists of lean, dried meat — usually beef, but bison, deer, and elk were also common — crushed to a powder and mixed with an equal amount of hot, rendered fat.

Over the course of the next three weeks, some of the boats were found by other ships, but others disappeared. In all 79 crew members, three gunners and 22 passengers were lost.

The captain and 154 survivors, including Mr McKechnie, were picked up by the 5,500-ton Glasgow-based Clan Line steam merchant ship Clan Alpine, and landed on St Helena.

Other survivors were found by various other vessels and landed in other ports.

If any reader knows more about Mr McKechnie, please