NOT everything stopped when the guns fell silent at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918.

The flow of paper from the War Office continued unabated, in particular the innocent sounding, but baleful, forms B104-80 and B104-82.

B104-80 informed a family that a loved one had been injured while on military service while B104-82, in its stark and almost impersonal language, brought the dreaded news that that loved one – husband, father, son, or maybe a daughter, had been killed, or was missing, presumed dead, or had died of wounds previously incurred.

Thus it was that when, in Helensburgh as elsewhere, the second week in November 1918 brought relief, rejoicing and no little thanksgiving, Mrs Mary Wells, who lived in a cottage along the road to Rhu, learned that her husband James, aged 36, had died on November 10, one day before the guns stopped. He died of pneumonia at a casualty clearing station in France. He was a local plumber who had enlisted as a volunteer in early 1915, soon after the start of the war and had served in the Army Motor Transport Division.

And James Wells was not the last from Helensburgh, although the war had ended. In the weeks and months following November 11 a steady stream of deaths is reported.

Some had already been reported missing and when the dust of battle finally settled and the War Office information systems had been checked and confirmed, families then received word which turned ‘missing’ into ‘believed killed in action’. Others died after the Armistice, often of wounds incurred much earlier, or from killer diseases such as pneumonia or influenza, against which immunities were much reduced.

Form B104- 2 was to be followed, from 1919, by the award, to grieving families, of what came to be known as the Dead Man’s Penny.

Form B104- 2 was to be followed, from 1919, by the award, to grieving families, of what came to be known as the Dead Man’s Penny.

These were bronze plaques, about the size of a modern CD, given to the next of kin of every serviceman and woman from Britain and the Empire who had died in or as a result of war service.

The plaque depicted Britannia holding an olive wreath of peace, together with a lion triumphant over a destroyed German eagle.

The name of the deceased was inscribed – but, in a faintly surprisingly enlightened decision, no rank or decoration was inscribed on the plaque, on the commendable basis that there was seen to be no distinction between the sacrifices made by different individuals.

Almost 1.5 million were issued and they were still being awarded as late as 1930. A total of 450 tons of bronze was used up in their manufacture. Over 200 of these plaques came to families in Helensburgh, such was the local loss, as evidenced in the pink granite panels of the war memorial in Hermitage Park.

On various memorials you will often see the dates of the First World War given as 1914-19, rather than 18.I think there are two reasons for this.

One, as I have indicated, is that the loss of life continued as servicemen, and some women, were still dying as a result of injuries months into the following year – if truth be known, some died years later from what they had suffered.

The other reason is that although the Armistice was November 11 1918 that was not the official end of the war. That took place when the Peace Treaty was signed at Versailles on June 28 1919, five years to the day of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in far-off Sarajevo, the unlikely act which started the domino effect and catapulted all Europe and beyond into the catastrophe of this Armageddon.

When I title this article as ‘How Helensburgh ended the War’ I don’t mean to mislead you into thinking that I am about to make some startling revelation about some local person or event whose contribution to the war effort meant that our town was somehow particularly instrumental in bringing an end to the hostilities.

Rather, what I want to do is draw a rough sketch of what was going on here 100 years ago and how the town reacted to the end of war and the beginning of peace. And I take as my margins the 7 or 8 months from November 1918 to the Peace Celebrations of the following summer.

I acknowledge two principal sources for my information. For all that is local I rely — I hope wisely — on the pages of the Helensburgh & Gareloch Times which are stored in the local library and which take us to a distant journalistic world which was still filled with deference to class and authority, and yet at the same time was quite untroubled by the modern affliction of libel laws and the need to be PC.

My other source, for the more general picture, is a quite excellent and very accessible book called Great Britain’s Great War which gives a concise account of events and provides a fine social history of the time. I can thoroughly recommend it if you wish to gain a good picture of that awful event, without the minute detail of every military or political manoeuvre.

It is written by one Jeremy Paxman. As you can imagine the book is bold, forthright and to the point — and it is to that Grand Inquisitor of Newsnight and University Challenge that we turn to set our thoughts about that Great War into context.

Reflecting on the death of his own great uncle Charlie in the military disaster that was Gallipoli in 1915, Paxman tells us:

I doubt I shall ever go to see his memorial (In Turkey) or that my children will. In the one hundred years since it began, the First World War has slipped from fact to family recollection to the dusty shelves of history, too incomprehensible in its scale, too complicated in its particulars, to be properly present in our minds.

It is no longer our fathers’ or even our grandfathers’ war but something that happened to someone who might or might not have had our name, who possessed perhaps a recognisable nose or mouth but who has nothing really to do with us. The very last military survivors of ‘the war to end all wars’ died in the early years of the 21st century, at which point bloody experience finally gave way to print and theory, and the whole thing is now as far distant from us as the Battle of Waterloo was from Uncle Charlie when he died in Gallipoli in 1915.

Bridging that ever-increasing time span and the growing faintness of the people and voices of that time is something tackled by Peter Jackson in his new documentary entitled ‘They Shall Not Grow Old'. Jackson has done some remarkable work with the old jerky monochrome footage filmed in the trenches, slowed it down and coloured it, added sound and words, courtesy of expert lip-readers, used voices of veterans recorded by the BBC forty or so years ago – and succeeded in moving our understanding of the spirit and the suffering of the First World War from the Charlie Chaplin-esque images to something very real and to which we can more easily relate.

By way of emphasis of that gulf of time and times between then and now, Paxman describes the British Army on parade at Aldershot on a summer’s day in 1914 – in other words just before the outbreak of war:

Four brigades of infantry and one brigade of cavalry, attended by batteries of field artillery, horse artillery and engineers. Most of the infantry wore scarlet tunics, the riflemen dark green, with cavalry-men in cherry-coloured breeches and Highland regiments in kilts and bonnets. There were 2000 horses on display – a magnificent, heart-warming spectacle. But there was not a single motorised vehicle to be seen.

Of course, upon declaration of war in August 1914 things changed and moved very quickly indeed. Mobilisation had been painstakingly prepared for.

Reservists were summoned by telegrams from Post Offices which were kept open 24 hours a day; transport, uniforms and pay were provided with a speed we would now gasp at. In five days 1,800 troop trains were laid on to Southampton alone, never mind other ports and within three more days a huge force embarked for war from these ports all around the country – but not before, as required by mobilisation regulations, the officer corps had been instructed to send off their swords for sharpening.

Helensburgh, of course, was a much smaller town than it is now. The enlistment in Helensburgh would mirror that of communities across the land.

While the principal army recruitment was into the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders — despite the fact that at that time Helensburgh was not even in Argyll, let alone Sutherland — the regiments entered were many and varied, and of course there was a substantial intake into the Royal Navy, the world’s biggest and most powerful, and into the Merchant Navy and various auxiliary services.

Four long, hard, unimaginably devastating, traumatic and bitter years later, Helensburgh, with the rest of the country, had good reason to think that the end of this hell on earth was in sight.

But not before, earlier in 1918, the Allies had again stared defeat in the face when the German army made some astonishing advances and were only just repulsed. However from mid-October victory and peace were being openly talked of with confidence in the local press and the announcement when it came on November 11 was already widely anticipated.

We need to remember that it was simply a ceasefire, a halt in hostilities, and there were many both at home and on the battlefields who remained to be persuaded that it was more than just another lull in the fighting — and that a lasting peace was in the offing.

At the time when the announcement was finally made, much of Helensburgh life was rather shut down – not so much because of the war but because of the flu.

The worldwide epidemic of influenza came in several waves in 1918-19, each more devastating than the last. Erroneously, blame for this outbreak was laid at the door of the Spanish.

According to a recent TV documentary, it actually appears to have started with a mutation of bird flu in an army training camp in the heart of the United States. It spread like wildfire. There were few effective medicines and public health and preventive medicine were rudimentary by today’s standards.

The columnist in the local newspaper rather makes light of the situation, implying that working ten hours on Sundays and sometimes all night means that he has little time to catch the flu. He says:

I may say that I keep clear of the flu by the use of salt and water gargle. I saw this cure in the newspapers and although I never believe much of what I read in the newspapers I tackled this cure which has been successful. Most people think that there is no virtue in cheap cures. They believe in nothing that is not followed up by a doctor’s heavy bills. I may here explain that if such a bill were my alternative, I should have to die.

Be in no doubt though that this flu epidemic was not some unpleasant inconvenience. It was deadly and it was rife and local communities were almost at panic stations for fear of it. It has been estimated that globally between 50 & 100 million died from flu in the year or so around the end of the war. The best estimate for the global loss of life as a result of the conflict is about 10 million.

The flu death rate in the west of Scotland varied from one community to another. In the more populous industrial areas it was higher because crowded housing and daily working contact provided easy spread of the virus.

In Clydebank the death rate was 61 per thousand, meaning that 1 person in 16 died from influenza. In Helensburgh schools and offices were closed for weeks on end, partly because of staff illness and partly to discourage spread of the disease. Many of those elements of local life which were able, more or less, to be maintained in the course of the war, eventually succumbed to the flu at the very point when the war came to its end.

Life in Helensburgh, as throughout the country, of course, had been heavily circumscribed for the course of the war by DORA.

DORA stands for the Defence of the Realm Act which was passed on the day that war was declared in 1914. Its wording was brief and deliberately vague, its scope and powers almost all-encompassing and its sanctions startlingly severe. To quote Paxman :

This was a remarkable, catch-all piece of legislation, allowing the government to commandeer land and businesses and making it illegal for civilians to buy binoculars, fly kites, ring church bells or give bread to animals. Subsequent provisions of this law cut the opening hours of pubs, allowed for beer to be watered down and introduced British Summer Time.

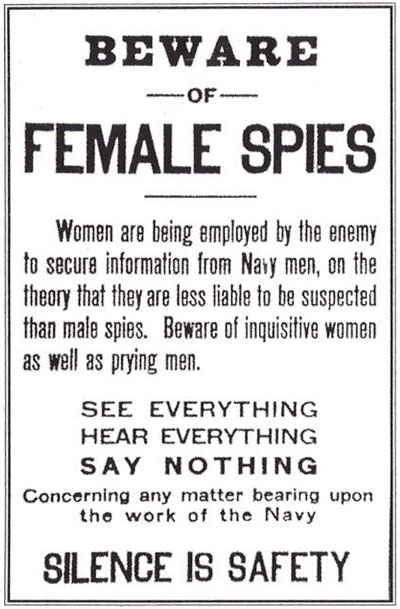

One of its more straightforward effects, though, was to make it an offence to discuss military matters in public or to spread military rumours. It also allowed the government to censor newspapers. It became an offence for a newspaper to report anything that might ‘prejudice recruiting’, prejudice relations with foreign powers’ or ‘cause disaffection with His Majesty the King’. It didn’t leave much room for dissenting comment on how the war was being managed.

This probably explains why the Helensburgh & Gareloch Times is fairly anodyne in its detail and comment on the war, in the interests of national morale, and reserves its more trenchant opinions for the behaviour of local politicians and minor miscreants.

Its publishers, Macneur and Bryden, who, of course also ran that that splendid emporium opposite the station, no doubt felt their other business hampered too, for the Defence of the Realm Act expressly forbade the sale of invisible ink – presumably to curb the activities of the many German spies believed to be at large in the land.

Its publishers, Macneur and Bryden, who, of course also ran that that splendid emporium opposite the station, no doubt felt their other business hampered too, for the Defence of the Realm Act expressly forbade the sale of invisible ink – presumably to curb the activities of the many German spies believed to be at large in the land.

DORA was often personified – and lampooned – as an interfering busybody, a strict and stern old woman, out to kill what little joy people had.As well as her forbidding aspect, and what she made illegal, she also took on the role of the great encourager or cajoler in times of austerity.

As the war went on the Act was used to try to tackle the historic British folly with alcohol, since hangovers were having such a bad effect on industrial production. As Lloyd George put it : ‘Men who drink at home are murdering men in the trenches.’

Beer was watered down and made more expensive in pubs with restricted hours. ‘Treating’, in other words, buying drinks for friends, was made an offence. In March 1916 a court in England fined a man £1 for buying his wife a glass of wine in a local pub. He claimed that she had given him sixpence to pay for the drink, but the court was unconvinced, fined the wife an additional £1 and, for serving them, also fined the barmaid £5 — the equivalent of £500 now. From today’s perspective, all very hard to visualise and even harder to justify.

By autumn 1918 many of these privations were seen as pointless irritations rather than necessary, in every jot and tittle, to the push for victory. In any event, the sense of relief in Helensburgh is palpable, as the newspaper reports moods and events as a community finally approached the light at the end of this wearisome and costly tunnel.

At 5am on the morning of November 11 it was announced that the ceasefire would take effect at 11.00am. The H> of two days later reports:

In Helensburgh the news that the armistice had been signed was conveyed in a telegram from Provost Duncan which was received after 11.00 o’clock, and immediately the church bells were rung, flags were hoisted on the town buildings, the Drill Hall and the Unionist Club.

In an incredibly short space of time flags were flying from many shops and dwelling-houses and for a time there was a great demand for flags so that those selling these soon got rid of their stock. The schools were dismissed for the day on receipt of the news and in Princes Street particularly crowds of people, young and old, gathered. Everywhere there were manifestations of joy that at last the long-drawn out war had come to an end.

A contingent of workers at Shandon Experimental Station arrived in a large motor about 12 o’clock, waving flags and cheering lustily, adding to the gaiety of the scene. Most of the shops in the town closed for the day at 1.00 o’clock. All afternoon the main streets presented an animated scene.

Shortly before 7.00 o’clock the Pipe Band and a large crowd gathered in front of the Municipal Buildings from the balcony of which Provost Duncan announced the good news. He said he felt it his duty to announce to them officially the news they had all heard today of their magnificent victory.

He rejoiced with those who rejoiced and his heart went out to those who had to carry the burden of sorrow. Helensburgh had indeed done its share in this wide world war. It had given many of its best and bravest sons and they would welcome the boys home who had carried the burden so well and so bravely.

The Provost concluded by calling for three cheers for the King, which were given enthusiastically, the people singing the National Anthem. The Pipe Band then set off to parade the streets, followed by a cheering and happy crowd.

The next day two Services of Thanksgiving were held in what was then Helensburgh Parish Church at the pier. The first, in the morning, was for children. It is reported that ‘the march out from the various schools along the public streets to the church was a sight never to be forgotten in Helensburgh.

At noon all the congregations united for a special service, together with the Town Council, Parish Council, School Board and wounded soldiers from Hermitage House Auxiliary Hospital. Mr Brown, of the John Street cinema, was even quicker off the mark and, the night before, the day of the Armistice, he hurriedly abandoned the scheduled showing of westerns and spy adventure and replaced it with a patriotic programme of images of the rulers of the Allies as well as the local Territorial and Volunteer companies.

The mood in the town, though, required some sensitivity, some moderation. The columnist in the local paper nine days later captured it well:

Last week was victory week and, although by this time, the initial rejoicings are about over, there soon will be many gatherings commemorative of the greatest conflict, the greatest victory in the annals of history. Never has the world touched such depths of grief or endured such terrible sufferings as those of the past four years.

City, town, village and clachan, they each and all have passed through the fires, and if those parents, wives, sisters, brothers, with hearts seared by recent wounds, have thought of us as selfish and perhaps noisy in our joys, let it be said that the noisiness was more hysterical than selfish.

It was the dam let loose, the floodgates open, the pent-up feelings of years breaking forth in an uncontrollable shout. For there are sore hearts today in many a home. Infinitely pathetic is the tragedy of those who made the great sacrifice, within, we may say, minutes of the last shot being fired. Victory within handgrasp, they passed from us. Young lives of good and greater promise: they have stopped at the threshold.

When the immediate celebration and relief had been expressed, Helensburgh, like everywhere else, applied itself to some pressing questions :

- How best to mark the deaths in the war of some 200 Helensburgh men and one woman (the number was eventually to rise to 214)

- How to welcome home those who had fought and survived

- How to provide for the needs both of returning servicemen and women – and local families bereaved and thus, in many cases, deprived of a breadwinner

- How to mark the eventual signing of the Peace Treaty

All the signs are that the people of Helensburgh were unanimous that something should be done, such was the momentous impact of the years during which they had lived and some had died.

But if we imagine that there was unanimity as to what should be done, well, remember that this is Helensburgh and there would be no shortage of opinions and disagreements ably expressed in all sorts of directions. So there was nothing simple about any of it and the four questions before the town were intertwined in such a way that there was a danger that they would have a detrimental effect on each other.

Well-meaning citizens started to do their own thing. A lady gave £5 for a Christmas tree to brighten up people’s lives and another proposed that a fitting ‘green’ memorial to the fallen would be for townsfolk to plant ‘long-lived In Memoriam’ trees in their gardens with metal labels giving names and dates.

The poor could plant one for 7/6 and the upkeep would be minimal but also something to be cherished. People might choose their own variety, large or small, and any fruit produce from such trees would go to the hospital or be sold for charity. I don’t think anything came of this idea – but it may have been an impetus to the street tree planting programme.

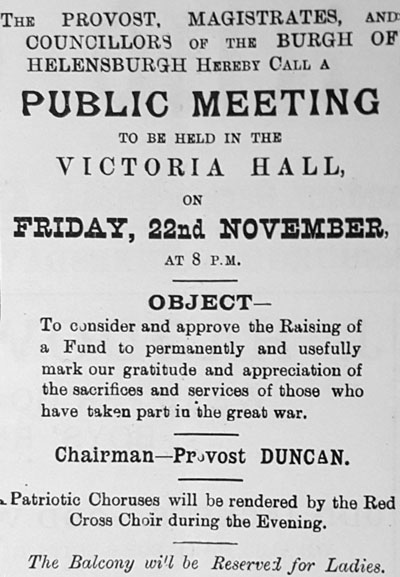

Eleven days after the Armistice a public meeting was called in the Victoria Hall by Provost Duncan and Magistrates. In the advert we are told that patriotic choruses would be rendered by the Red Cross Choir – and that the balcony in the hall would be reserved for Ladies, the implication being that the purpose of the meeting was men’s business – to consider and approve the raising of a fund to permanently and usefully mark our gratitude and appreciation of the sacrifices and services of those who have taken part in the great war.

Eleven days after the Armistice a public meeting was called in the Victoria Hall by Provost Duncan and Magistrates. In the advert we are told that patriotic choruses would be rendered by the Red Cross Choir – and that the balcony in the hall would be reserved for Ladies, the implication being that the purpose of the meeting was men’s business – to consider and approve the raising of a fund to permanently and usefully mark our gratitude and appreciation of the sacrifices and services of those who have taken part in the great war.

By early December the committee appointed from that public meeting reported and interpreted its remit as ‘first and foremost to do honour to the noble dead by the erection within the burgh of a fitting memorial in which the names will be inscribed.

With the remainder of the fund, it is hoped to aid the living in a material and permanent way, the maimed and broken men who have no helpers and the widows and fatherless in their affliction.’ They also reported early donations of some £500 received, from some of the town’s leading citizens.

This report sparked considerable and sustained activity in the letters column of the paper by those who were singularly unimpressed at the thought of large sums of money being expended on stone monuments which would certainly meet the ‘permanent’ part of the remit but certainly not the ‘useful’ part, which would inevitably be allocated the left-overs, if any, from the stone memorial.

Some were fearful of a bland and dull monument, and were anxious to ensure a stone memorial of artistic quality and not one ‘left to the hands of the eager monumental mason’ of whose trade the writer clearly had a low opinion.

A plea was made for not rushing anything, for careful and measured consideration – and by way of bad example reference was made to the ‘lamentable aberration which had led, during the war, to the painting over of the names of German composers on the walls of the Victoria Hall.

The controversy raged for some months with a voluble minority appealing that the dead of the war deserved more than a dead piece of stone and that instead their memory should be honoured in some living and useful institution, to be made available for the benefit of those returned from the war as well as the general populace – such as public baths or a gymnasium or a library or club rooms.

School bursaries were also suggested, as was the building and endowment of cottages for war widows. Such was the disquiet that it became clear that the appeal for funds was not meeting with the success it had assumed, that the result might be a cheaper and inferior memorial, and requests went out to the citizenry to rally to the cause.

This in turn provoked the response that people were withholding their contributions until clear, costed and definite proposals were provided by the committee, both for a stone memorial and some other useful functional provision for the town. This chicken and egg situation was exacerbated by the fact that it became evident that the plans and decisions would be made solely by those who subscribed to the fund and not by the Town Council or general populace.

One correspondent, perhaps not entirely in touch with reality, felt that the slow response to the fund was partly due to the fact that subscriptions were to be made at the bank and that the working classes are embarrassed to walk into a bank and put down their small sum without a little hesitation. His solution was to propose a different means of accessing the funds of the working classes by way of a fancy dress parade with collecting tins and then, in the evening a fancy dress ball for the richer people.

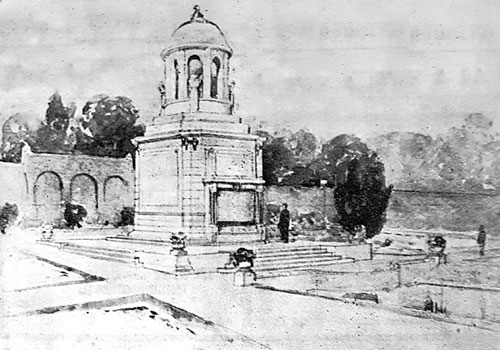

In any event the committee stuck to their task and their guns, and by April 1919 they produced a final report which proposed a stone memorial and garden in Hermitage Park, designed by the eminent architect Alexander N.Paterson –who was of course a resident of the town and the brother-in-law of an influential town councillor – at an estimated cost of some £3,000 which, perhaps rather too conveniently, was within a few pounds of the total sum raised for the project.

In any event the committee stuck to their task and their guns, and by April 1919 they produced a final report which proposed a stone memorial and garden in Hermitage Park, designed by the eminent architect Alexander N.Paterson –who was of course a resident of the town and the brother-in-law of an influential town councillor – at an estimated cost of some £3,000 which, perhaps rather too conveniently, was within a few pounds of the total sum raised for the project.

The columnist in the Helensburgh & Gareloch Times, clearly exasperated by those who were saying, yes, that’s fine, but what has happened to the ‘useful’ element of the town’s commemoration of the war and its dead, thundered at the quibblers, as he called them.

Recognising that the matter of the burgh’s war memorial had become a very vexed question which it should not have become, he attacks those who continued to call for a change of direction towards the provision of a ‘useful’ memorial. He questions why so?:

Is it that many of those who during the war benefited by the lives of those soldiers are also to benefit by their deaths? May we only have reference libraries and clubs on the termination of bloody wars? If we desire a pavilion in the cricket ground must we wait for the next fight? There is something horribly calculating about such proposals.

Then, rounding on those who still muttered about the expense of the war memorial, he really lets fly:

We have wasted millions on war contractors, on spendthrift munitioneers, on the hordes of leeches attached to the multitudinous War Departments, but when we come to the question of a few paltry hundreds of pounds to be spent perpetuating the memory of men who did not bleed their country but bled and died for it – oh! the expense, the expense! Those men gave everything – we quibble over threepenny bits.

We all of us know how much needed clubs, baths and all the rest of it are, but what in the name of common sense have these things to do with dead heroes? Let us do one thing at a time, and if we cannot find reading-rooms without hinging them in a pitifully niggardly way on to the sacred question of our dead, may we never have reading rooms, clubs or anything else.

In pay, allowances, everything, the majority of our dead soldiers were treated vilely during life. They suffered from intensive cheese-paring while others rioted in wealth. Now that the brave lads are dead let us, in heaven’s name, treat them decently. Let us get away from wretched, sordid quibbling, and always remember that the memorial is a memorial to the dead. It is not a portion of our plan of reconstruction.

By the end of March 1919, less than five months since the Armistice, the committee made its final report to the subscribers and announced that the design for the memorial would be available for view at Baillie Morrison’s jewellers shop in West Clyde Street.

Their report indicates that they had carried out a careful and exhaustive examination of a number of possible locations for the memorial – Cairndhu Park, Walker’s Rest, Colquhoun Square and Hermitage Park, settling eventually on the last, of course. However, I do wonder how seriously they did look at other sites.

The newspaper four months earlier confidently advised both the committee and the general populace that, ‘while the matter must not be hurried, it must include an artistic fitting monument in Hermitage Park for those who have fallen’ – and additionally states that ‘public feeling also favours a memorial fund of two or three thousand pounds to assist necessitous cases of soldiers and sailors and their dependants in Helensburgh.’ Clearly our anonymous columnist is not greatly troubled by the need for consistency!

The memorial committee did want to go a little further. Noting that the memorial itself with the associated pond and garden work would take up all the funds ingathered, they had a vision that the fine north, east and west walls of the garden, after the demolition of a lodge house, would be developed to commemorate all the townsmen who served in the forces, not just the fallen, and also those, men and women, who had so nobly done their bit at home.

Further funds were invited for this additional work but the evidence on the ground today suggests that nothing further happened and that the idea did run into the ground.

The next important and sensitive task was to compile a Roll of Honour of all the men and women who had been on active service since August 1914, whether at the fronts or in hospital service at home or abroad. This Roll of Honour would be preserved in the archives of the Town Council, and a cheap replica would be published and sold to the public at a price which will cover the expense of publication, so that every home may be able to obtain a copy. I have never seen a copy and perhaps someone might tell me if this proposal was ever carried out.

The War Service Memorial took another three years to complete, was constructed by Trail Brothers, and was eventually dedicated on a summer’s day in June 1922. It was pretty much as we see it in its restored form today, with the obvious additions marking the Second World War.

At the time Hermitage House stood right in front of it and at the same time as the plans for the memorial were being approved, the Hermitage Red Cross Auxiliary Hospital wound done and closed its doors. Its job was done.

One of many such hospitals for the war wounded all around the country, Hermitage Hospital had opened in late 1914.

The Times reports on the important place it had in the town during the war years, of how, in the midst of horrors a dormant goodness had been awakened, that life in the hospital had been such as to break down foolish barriers, with the camaraderie of sex and section which it had brought about.

‘When the finished tale of world tragedy is written, we are sure that of its pages many will be devoted to our splendid band of nurses.’

And of the building, now of course long gone, the writer says:

‘Never till its stones have mouldered into dust will it be the channel of so much good service as it has been for the past four and a half years. To the now-disbanding staff, to Miss Keillor (matron) and to Dr Semple Young, (medical officer in charge), the thanks and gratitude of patients and of the community are deeply due and warmly accorded’.

Patients in the hospital were given a distinctive blue uniform, even though, as Jeremy Paxman says, they might not have many limbs to put in them. A total of 1,077 patients were cared for in the course of the hospital’s life, many from far afield, with wounded soldiers from the dominions among them.

Patients in the hospital were given a distinctive blue uniform, even though, as Jeremy Paxman says, they might not have many limbs to put in them. A total of 1,077 patients were cared for in the course of the hospital’s life, many from far afield, with wounded soldiers from the dominions among them.

The hospital, with its patients and staff is actually very well recorded photographically, an employee of the Town Council having been commissioned to do this as part of his duties. All the photos show staff and men invariably in good spirits and often acting up for the camera, sometimes making jolly of their injuries.

There is little evidence of the undoubted pain, trauma and horrific disfigurement which was often the mainstay of such hospitals – perhaps, in the interests of public morale and the continuing war effort, the photographer was instructed not to point his camera in the direction of the grotesquely injured.

There is little evidence of the undoubted pain, trauma and horrific disfigurement which was often the mainstay of such hospitals – perhaps, in the interests of public morale and the continuing war effort, the photographer was instructed not to point his camera in the direction of the grotesquely injured.

But the townsfolk who had the hospital in their midst would see well enough for themselves the awful evidence of the terrible weapons of modern warfare.

To quote Paxman again :

Machine guns made no distinction between the classes - those who ate their peas off their knives and those who didn’t. In 1917-18 the newspapers were full of casualty lists, curtains were drawn in family homes of all qualities, pavements were swept with the black dresses of sorrowing women. The wounded were everywhere, for all to see.

There was one particular type of wound that was especially distressing to look upon – the facial injury. Sentries raising their heads to look out into no man’s land, men advancing into machine-gun bullets, an unlucky hit from a trench mortar, or a fire in a ship or a plane, trench or tank, above all the flying shrapnel from exploding artillery – there were multiple opportunities to acquire some of the worst wounds of all.

The dead would later be memorialised. The disfigured who had lost their noses, mouths or jaws, whose faces had perhaps been almost entirely blasted away, lived on as living gargoyles. It is impossible to exaggerate the horror of many of these wounds. Quite apart from the physical consequences – a smashed face or missing jaw condemned a man to sucking his food through a straw for the rest of his life – there was the awful emotional cost.

The wife or mother who had waited anxiously for your return blanched when she saw you. Your children might well flee in terror. Those 21st century consumers whose vanity drives them to make plastic surgeons rich might care to reflect on the origins of the procedures upon which they embark so casually.

The horrors of that Great War at least served to give increased impetus and urgency to medical research and development. There were considerable advances in those four years, and their aftermath, in the fields of antiseptics, anaesthesia, orthopaedic and restorative surgery. Paxman again :

By the age of ten a schoolchild might have seen more damaged bodies than a 21st century adult could ever expect to see in a lifetime. Before the First World War they might have caught the occasional glimpse of a maimed veteran of an imperial war tramping the roads or lining up for admission to the casual ward of a workhouse.

Now, though, mangled bodies were a fact of life. And they told a very different story to the one the public had been shown in the newspapers and cinema newsreels.

As far as Helensburgh and the end of the war is concerned, what I have concentrated on has been rather centred on Hermitage Park – the hospital and the memorial, which was supposed to do something for the returning and the living, and their dependants, as well as for the fallen, but which seems to have fallen short in that good intention.

There were lots of other challenges to be faced in addition, and which almost every community encountered, for example the issues posed by the demobilisation of the armed forces – these were humanitarian, economic and social concerns.

It quickly became evident in the town that the demobbing would not be an instant avalanche of returning heroes, and that the logistics of tidying up a major war theatre and its equipment would take some time, quite apart from the need to keep some of the forces abroad to ensure that the flames of war were properly extinguished.

There was national debate about the order of their coming home – should the first to come back be those who had served the longest – or the shortest time? Were their jobs still open to them – jobs which in many cases had been taken up during the war by women, who had gained a grudging respect? And how to mark the return of the servicemen when they did come. Our columnist from the local Times in February 1919 continues on his trenchant way:

Within the past week or two prisoners of war have been returning from Germany, and nothing in the way of public welcome has been extended to them. The men endured for us not only all the risks of the war but the hardships of captivity at the hands of an unscrupulous enemy.

Some again have won military honours, of which the toiwn has every reason to be proud – but there have been no acknowledgements. Other townsmen who have been in the think of it for three or four years have been demobilised and are back in civil life again. They don’t want any fuss made about their return but the town has a duty and should not fail to show its gratitude and appreciation.

In the late spring a Civic Reception was eventually held for the returning men, over two nights in the Victoria Hall, in order to accommodate everyone. Among much speechifying by the great and the good, the Provost paid tribute to both the living and the dead, noting that some 1,000 men from Helensburgh had recruited over the course of the war, some 12.5% of the population.

Local servicemen’s associations were formed, most notably a branch of Comrades of the Great War who did sterling work with the social needs of the dependants of the war’s casualties and fought their cause with vigour on the political stage, local and national. The Comrades was one of a number of organisations which later combined to form the British Legion.

To many of the men discharged from the forces, Britain felt nothing like the ‘land fit for heroes’ held out to them by Lloyd George, who, of course, always found it much easier to promise than to deliver.

Those selected for demob got four weeks leave, a railway warrant and ration book and some civilian clothes. They were allowed to keep their army greatcoat but if they did not want it they could hand it in at an railway station and get £1 for it. After that they were on their own with virtually no state or local authority support.

Housing was an urgent issue and Helensburgh set about it early in 1919 when the burgh appointed George Paterson as architect and instructed him to consider sites and plans. Drumfork and the west end of King Street, what we know as Ardencaple were considered, Ardencaple being agreed upon and a scheme of 60 houses to be built by early 1922 (left, behind Cairndhu and Ferniegair).

Housing was an urgent issue and Helensburgh set about it early in 1919 when the burgh appointed George Paterson as architect and instructed him to consider sites and plans. Drumfork and the west end of King Street, what we know as Ardencaple were considered, Ardencaple being agreed upon and a scheme of 60 houses to be built by early 1922 (left, behind Cairndhu and Ferniegair).

But approval was not forthcoming before an outbreak of nimbyism, with the Provost, clearly having had his ear bent by notable citizens in fine houses, being forced to declare that the Council must be careful and proceed with caution, that they had to take into account the interests of the householder and that they must, as far as possible, preserve Helensburgh for Helensburghians – for they did not wish to attract people from all over the country to come to Helensburgh to have houses built for them.

Spring of 1919 wore on to summer and when the terms of Germany’s surrender were finally agreed on June 28 there was further marking in the town by the way of flag, celebration and special church services. But nationally the signing was to be marked by an official celebration of the Declaration of Peace, marking the formal end of the war, on Saturday July 19.

Obviously, the west of Scotland was not consulted in the fixing of the date for this was going to clash with the Saturday of the Glasgow Fair, which was just ‘not on’. The Council, like other towns, decided on a more convenient date, selecting September 8, although this was subsequently changed to August 4, the fifth anniversary of the outbreak of the War.

But July 19 was not ignored – bonfires were lit on the two hills overlooking the burgh, the residents of the town having been earnestly encouraged to display flags, buntings and decorations.

Marking the event twice had the inevitable effect of spreading the enthusiasm and energy with the result that when August 4 came and went the Times felt that the level of interest was perhaps less than it might have been.

Clearly the editor was not persuaded of the merits of delaying from July 19 as he starts his report: for reasons which were no doubt deemed adequate by the Town Council it was decided that the Peace Celebrations in Helensburgh should take place on Monday August 4. Rain fell heavily in the early part of the day but happily, for the comfort of all concerned, the afternoon and evening were fine. The Municipal Buildings led the way in the decoration of buildings, with a design by Mr Cormack, the burgh officer, which showed 1914 in flames of war and 1919 with the dove of peace – a repeat of the decoration for 19 July.

The bulk of the entertainments were focussed on the Public Park in East King Street and comprised presentation of medals to servicemen and ex-servicemen, children’s and adult races, football tournaments, pipe bands, a fancy dress cycle parade. When darkness fell there were brilliant fireworks followed by a dance in the Victoria Hall.

Helensburgh, with the rest of the land, was now at peace – at least from war with Germany, at least for 20 years. Life, at least for some, began to return to normal. For many of course, that was not an option – such had been the loss of life and loved ones, and for others the loss of health, employability, breadwinning, dignity and sometimes reason.

The Times, while not losing sight of such plight, gradually returned to the familiar territory of reporting concerns and events peculiar to the burgh. Here are a couple, of snippets, selected at random from the editions of 1919. Firstly the problem of boy racers:

The boom in motoring, this summer, is expected to eclipse all previous records, and those who live in the vicinity of main roads are dreading the recurrence of the dust nuisance. It will be particularly bad, because the cars will be greater in number and the roads, with all the tarring, are still a long way from dustproof.

We shall see the value of consideration in driving though the public would have been better served had they kept control of speed in urban places until the roads were fit for the 20 miles an hour work.

By the way, who looks after motor speeds within the burgh? There are several cyclist scorchers who must have tied up their speedometers and one or two of the drivers will go on, unless they are warned, until they too have an accident.

And as if that were not enough for the local constabulary to deal with we have the following :

Unfortunately there have been one or two nasty attacks on the local police during the past few weeks. There are policemen in this world of whom the least said the better, but, distinctly, Helensburgh is fortunate in its boys in blue. And they must be protected and the Bolshevist spirit smashed.

A friend who is wise beyond his years tells me that if it were not for the women there would have been no fight or no police assault on a certain evening that he knows of. The two men, he says, fought about a girl.

Each man was evidently prepared to shed his last drop of blood for her. On these grounds the contest between them had a certain amount of applause, but when it transpired that both suitors for the hand of the fair one were married men, there was a slump in enthusiasm.

But to conclude we return to the mixture of grief, relief, pride, victory, loss, thanksgiving and waste which was felt then and is recognised now as we commemorate the 100 years which have elapsed, in these words by D.Stewart Wright, about whom I can find nothing and whom I presume to have been a local wordsmith.

But to conclude we return to the mixture of grief, relief, pride, victory, loss, thanksgiving and waste which was felt then and is recognised now as we commemorate the 100 years which have elapsed, in these words by D.Stewart Wright, about whom I can find nothing and whom I presume to have been a local wordsmith.

They appeared in the Times a week after the Armistice. It is a poem entitled ‘God keep our Memory Green’: