PAINTING of coastal rocks to enhance an existing feature is a particular form of artistic and cultural expression — and one of the great examples is ‘King Tut’ on the shore at Kilcreggan.

Painting rocks happens elsewhere, but there is a remarkable concentration and variety on the Clyde Coast.

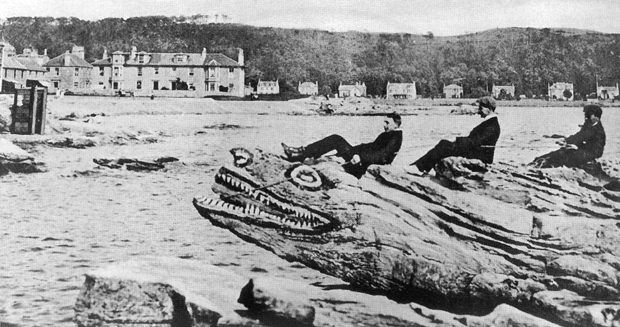

In ‘King Tut’ (pictured left in the 1920s) the Helensburgh district boasts what is almost certainly the oldest, and definitely one of the most stylish.

In ‘King Tut’ (pictured left in the 1920s) the Helensburgh district boasts what is almost certainly the oldest, and definitely one of the most stylish.

Heritage Trust director Alistair McIntyre has researched this subject, and says that other parts of the Clyde Coast also contain noteworthy painted rocks.

“One has been immortalised in popular literature, while another has provoked political controversy in the national, as well as the local, press,” he said. “Generally speaking, particular examples are often sufficiently well-known that they are in tourist literature.

“The propensity of mankind to perceive familiar forms within inanimate nature appears to be set deep within the human psyche. Who, for example, has never spotted a face within a passing cloud?

“Many natural features in the landscape have Gaelic place-names derived from familiar shapes like parts of the human body, sometimes expressed in a remarkably frank way.”

So it is with rocks, with those near the coast drawing attention because of their physical prominence. But while they are familiar shape, it takes the skill of the artist to produce a recognisable work of art.

Not everybody likes them, so the question is often where does art end and vandalism begin?

Coastal rock art is often prominent from both land and sea, so it is important that when someone applies paint to nature, he or she produces a result that will generally be appreciated rather than criticised.

‘King Tut’, sometimes known as ‘Tut-Tut’, is a boulder, cast high and dry by an Ice Age glacier, and it is known to geologists as an erratic.

As many people already know, the name comes about from a perceived resemblance to the face-mask of the Egyptian boy-pharaoh, King Tutankhamun, discovered during Howard Carter’s excavations in 1922.

The rock, however, had already been painted as a face long before that — one source gives 1851 as the first occasion, while another says the 1860s.

Did the appearance of the rock in the wake of the tomb excavations suggest to people an existing resemblance to the mask of the pharaoh, or did this just stem from subsequent re-working?

“Whatever the case,” Alistair said, “the point is that the rock is almost certainly the earliest example of painted rock art on the Clyde Coast. The genre, then, is a relatively modern phenomenon.”

According to a former minister of Craigrownie Church, the late Rev C.K.O.Spence, the original rendering was conceived and executed by a Mr Spy, then employed locally as a house-painter.

At some point, the custom or practice came to be that re-painting of the rock was carried out by the occupant of Huddersfield House — later known as Windward House.

Local tradition has it that the painter worked unseen. But Norman Tullis has often been named as the person who for many years saw to the rude health of the painting.

A photograph of the rock around the time of Howard Carter’s monumental discovery shows a head which looks distinctly grumpy, displaying as it does a rather ferocious-looking set of teeth.

This is not surprising, perhaps, as it is suffering the indignity of at least eight people standing on top or leaning against it.

However, in keeping with his new, royal, status, re-painting took on a regal, rather than raging, demeanour, thanks to some subtle alterations, and this styling has been faithfully maintained until the present day. During World War Two, a ‘V’ for victory was incorporated.

Although ‘King Tut’ (pictured right in 1951) is well-loved by visitors, tourists and local people alike, this does not mean that there was never controversy.

Although ‘King Tut’ (pictured right in 1951) is well-loved by visitors, tourists and local people alike, this does not mean that there was never controversy.

In 1996, some people were appalled by the latest face-lift, as the colours chosen were lurid, psychedelic yellow, pink and green. The painter was later revealed as a visitor from Australia.

Subsequently, re-workings were happily more in keeping with the image.

A particularly good rendering in colour and design was that carried out in fairly recent years by the pupils of Kilcreggan Primary School, under adult supervision.

Another repainting featured a group which included included Gail Young, along with John Jarvie, Julie Wright, Abigail Brown, Neil Young and Tony Belk, helped by young people from the district.

Elsewhere on the Clyde, two painted side-by side rocks on the north coast of Bute (below left) have the distinction of being immortalised in the writings of famous novelist and journalist Neil Munro, a Helensburgh resident from 1918-30.

Initially written as a series of humorous short stories for a newspaper, the Para Handy tales, as they came to be known, were later published in book form because of popular demand.

Subsequently they formed the basis of several series on TV, with such well-known actors as Duncan McCrae, Roddy McMillan, and Gregor Fisher in the leading role.

At the centre of the action is a certain Para Handy, skipper of a Clyde puffer, and his crew.

One of the tales, written in the period 1906-1911, is entitled “The Maids of Bute”. In it, Para Handy reveals to his incredulous crew that it was he who was responsible for first painting the rocks, which overlook the Kyles of Bute.

One of the tales, written in the period 1906-1911, is entitled “The Maids of Bute”. In it, Para Handy reveals to his incredulous crew that it was he who was responsible for first painting the rocks, which overlook the Kyles of Bute.

According to him, when employed as a hand on a MacBrayne steamer, the Inveraray Castle, he was prevailed upon by the captain to render the rocks more lifelike through the judicious application of some paint.

He was disembarked at Tighnabruaich, with instructions to take overnight accommodation, hire a small boat, and proceed across the Kyles with paint and brushes.

The self-conscious Para fobbed off inquisitive local people on the pretext of marking out the site of a new MacBrayne harbour.

To quote his own words: “The north end of Bute is a bleak, wild and lonely place, but when I was done pentin’ the Maids, it looked like a large population. They looked that neat and cheery among the heather!

“Mery had a waist you could get your hand around, but ‘Lizabeth was a broad, broad gurl. I know they’re only stones with rud and white pent on them, but they’re good enough for towerists.”

Painted Clyde rock art tends to feature these two colours, along with black. Para Handy lamented: “The only thing that vexed me was that I only had the rud and white.

“If I had magenta and blue and yellow, and the like o’ that, I could have made them far more stylish. I gave them white faces and rud frocks and bonnets.”

Had it been a real story, the episode would have dated to pre-1895, when Inveraray Castle was scrapped.

A painted Clydeside boulder that certainly hit the headlines is one known as ‘Jim Crow’. Like ‘King Tut’ a glacial erratic, it lies on the foreshore at Kirn, Dunoon.

It would appear that the rock was given the name in the 1880s, with the first painted image in 1904.

At one end is a painted head, said to resemble that of a jackdaw, although a penguin might also spring to mind. Some maintain that the name stems from that of a local boatbuilder, but this has never been substantiated.

Long accepted as a tourist feature on the foreshore, rumblings of discontent began to emerge early in the Millennium.

It was pointed out that the name bore unpleasant associations of racism, particularly as experienced in the U.S.A., and that the colour scheme in use helped reinforce this connotation.

Feelings ran high, and the Scotsman newspaper reported in the summer of 2011 that an extraordinary battle had broken out amid claims and counter-claims of racism and secretive night-time acts of sabotage.

It described how the familiar image had recently been painted out with grey paint, this being for the third time in as many years.

Another report quoted those responsible for the painting out as allegedly stating that, should the painting be reinstated, they would return as often, and for as long as necessary, to paint it out again.

The small island of Great Cumbrae has at least two noteworthy painted rocks, and the provenance of both is well established.

The Crocodile Rock, which is on the foreshore at Millport, has been dated to around 1913.

The story centres on a group of retired businessmen living on the island. They had the habit of meeting at noon for a refreshment in a local tavern.

They were termed by local wags as the ‘Toddy Brigade’. One of their number, Robert Brown, a retired Glasgow architect, came out of Paterson’s Tavern one day after the customary tipple, and remarked to his companion: “I have an idea that rock is awful like a crocodile.”

Next day, he was spotted walking down the street with tins of black, red and white paint and several brushes. From that day onwards, the Crocodile Rock has sported the same colours.

Children love to have their pictures taken astride the fearsome creature. The rock is acknowledged to come alive when the tide comes in and waves break over the huge set of jaws.

Another much-loved rock on Great Cumbrae is the ‘Indian’. Unlike some of the others, this is not a boulder, but forms part of an old sea-cliff at the island’s north end.

It was formed after the last Ice Age, when, for a period, sea levels were much higher than today. The date of painting has been attributed to the 1920’s, so this is one of the latest examples of its type.

The name of the painter is also known. It is believed that someone known as “Fern Andy”, who lived in a cave, was responsible. He eked out a living by selling ferns.

Best seen in profile, the face looks remarkably lifelike, even seemingly sporting a braided lock of hair. Is it all entirely natural, or had Fern Andy helped things along with a little carving as well as paint?

There is yet another famous coastal rock on Great Cumbrae, but it is entirely natural, and has no paint. This is the Lion Rock, which does look remarkably like a crouching lion when viewed from some angles.

As it is a large and very shattered volcanic dyke, with all sorts of joints and cracks. Any attempt to paint this rock would be a formidable challenge.

There has been talk of human intervention, but the motivation here is purely one of trying to stabilise the existing structure for fear that the classic lion outline might be lost through natural processes.

There is one class of Clyde Coast painted rocks whose main attraction to artists is somewhat different.

Holy Island, which lies close to the much larger island of Arran, was sold to the Samye Ling Buddhist Community in 1992.

Holy Island, which lies close to the much larger island of Arran, was sold to the Samye Ling Buddhist Community in 1992.

As the name of the island suggests, it has long been considered a place with sacred associations, and this has been sympathetically continued by the Kagyu School of Tibetan Buddhism.

Among other works, there are painted rocks, including one portraying an image of Marpa the Translator (right).

Another example of rock art that is spiritually driven is to be found on the island of Davaar, just off the Kintyre Peninsula.

Here, in a cave, is the famous painting of Christ on the Cross, the work of Archie McKinnon, a local art teacher, which dates from 1887. The location for the painting is said to have been revealed to him in a dream.

Re-touching has been faithfully kept up over the years, but there was a setback in 2006, when the painting was vandalised.

However, the damage was quickly rectified when the Art Department of Campbeltown Grammar School came to the rescue.