THE SALE and recent modernising renovation and expansion of the Old Milligs Tollhouse at the top of Sinclair Street in Helensburgh as a private residence brought focus to a fascinating class of buildings.

They actually hold a unique place in the story of local roads in this area.

Local historian and Helensburgh Heritage Trust director Alistair McIntyre has researched local toll houses and cottages, and he has provided the details which follow.

Local historian and Helensburgh Heritage Trust director Alistair McIntyre has researched local toll houses and cottages, and he has provided the details which follow.

The Old Tollhouse — a listed building — witnessed more of the comings and goings of humanity over the years than most homes in Helensburgh, given its roadside location at the top of the Blackhill.

Dating from 1832, it is one of a select band of such buildings in the area that have survived, and other examples including the former toll houses at Morlaggan, Ballyhennan and Luss.

So what is the story of Old Milligs Tollhouse, now so dramatically lit up at night and surrounded by striking new gates?

It sounds rather like a plot for Dad’s Army, but there was a cunning plan for the Old Milligs Toll House to be the setting for a battle with any German invaders in World War Two.

The idea was to dig holes in the road opposite the house, and then install pieces of railway track at an angle to prevent tanks rolling down Sinclair Street! Fortunately it was not required.

A key piece of legislation that went through Parliament in 1807 was a local act which related solely to the roads and bridges of Dunbartonshire.

It paved the way for the establishment of turnpike roads in that part of the county to the west of the River Leven.

The name ‘turnpike’ comes from a form of rotating barrier, but it is not clear if these featured as such on local roads. Possibly a broad gate was more likely, perhaps with a stile or small gate for pedestrians.

These barriers were controlled by the toll-keeper. Pedestrians were generally exempt from any charge, but those on horseback, those with carts or carriages drawn by beasts of burden, and those conducting livestock like cattle or sheep had to pay a fee for use of the road.

But why was such a system brought in? The motivation most likely stemmed from a growing awareness that existing roads were inadequate for the transport needs of a rapidly developing economy, and that the system which had hitherto underpinned their maintenance was simply not up to the job.

By 1816, a number of toll barriers and toll houses were in place at various locations.

They initially consisted of Dalreoch, Drumfork, Garelochhead and Morlaggan, all on the Dumbarton to Arrochar road, while on the road from Dumbarton to Luss, similar provision was made at Dalreoch, Auchendennan and Luss.

Dalreoch and Drumfork were both double tolls, with the former serving both the Arrochar and Luss roads, while Drumfork served the Arrochar road and the one from Drumfork Ferry to Duchlage, just south of Luss.

This road had been built around 1786 by the 5th Duke of Argyll, and in consequence was known as the Duke’s Road. Since it cut across country, it was classified as a cross road, as distinct from the two north-south highways.

The County Act of 1807 ran for 21 years, and so in 1828 another county act was put through Parliament.

So long as acts like this had an M.P. willing to act as sponsor, passage through Parliament does not seem to have been too onerous, the main obstacle being the expense.

It cost several hundred pounds, and some counties never adopted the turnpike system — Argyllshire being one example.

The Act of 1828 paved the way for a number of changes. The Loch Lomondside road was now made turnpike north of Luss.

The toll bar at Garelochhead was discontinued as the tollhouse was not custom-built and was not well located for catching all passing traffic, so a new one was set up at Shandon.

Morlaggan was set aside, and a new toll point set up at Strone  ), near the present and soon to be expanded RNAD Glenmallan Jetty.

), near the present and soon to be expanded RNAD Glenmallan Jetty.

Tolls on roads were always unpopular, and people would often go out of the way to avoid the check-points where possible. There was thus an element of cat-and mouse between the authorities and road users.

Another change concerned Helensburgh. With the growth of the town, a new road had been completed over the Blackhill shortly before 1832. This offered a link to the Loch Lomondside road at two points, one near Muirlands, and the other at Arden, both as they are today.

It was decided to make the new road turnpike, this being at the expense of the Duke’s Road. Drumfork toll continued to function, but thereafter only served the Dumbarton to Arrochar road.

Without the benefit of income from tolls, the Duke’s Road probably deteriorated fairly quickly, coming to be known in time as the Old Luss Road.

So in 1832, the Blackhill road witnessed the construction of a custom-built toll house at the top of Sinclair Street, linked to a toll barrier.

As with the Duke’s Road, the one over Blackhill was classed as a cross road. It remained in use as a turnpike road until 1883, when toll roads were abolished nationally.

Some counties with tolls discontinued them before this date, but Dunbartonshire retained tolls until the end.

The toll-keepers were appointed through what was an annual auction, or roup, of tolls.

Each year, prospective tollkeepers met at the Dumbarton Arms Inn, otherwise known as the Elephant Inn — the Dumbarton coat of arms prominently features an elephant with a protected fighting platform, a ‘castle’, on its back.

The right to operate a given toll from Whitsun to Whitsun was put up for bids. The highest bid was usually the successful one, though sureties were required. In practice, some tolls saw frequent changes of tacksman, as they were termed, while others tended to go to the same person in successive years.

A number of those taking part in the bidding process were essentially businessmen. A good example is Allan Lawson, who often held the tack for sm,keveral different tolls at the same time.

As such, he would not normally have been toll-keeper himself, and would have arranged for other people to actually operate a particular toll. Such persons would of course have been paid less than the bid price.

At the other end of the spectrum, a few tolls were operated by widows, who no doubt depended heavily on the income generated. One example is Elizabeth MacLellan, who for many years operated the toll at Strone.

The toll house was essentially a tied house as the successful bidder had the use of the house over the next year.

As in any auction, those taking part had to make a judgement on just how much to bid. Net income comprised takings from the toll minus the bid price — and obviously it was possible to make a loss as well as a profit.

Milligs Toll House saw quite a few tenants over the years, including in 1850-51 William Bryson, 1851-52 Alex Walker, 1852-53 William Bryson, 1853-54 Allan Lawson, 1855-56 a Mr Jardine, 1863-64 John McKay, 1865-1869 Robert Wright 1873-1875 William Brock, 1882-83 William Brock.

There at the time of the 1851 census was head of the household William Bryson (31), a gardener born in Old Kilpatrick, his wife Margaret (33) from Maybole, and their four young children aged from one to nine.

William gave his occupation as gardener, rather than toll-keeper, so perhaps his wife acted as toll-keeper? With such a young family, that might have been tricky. Much would have depended on activity at the toll.

William was again tacksman at Milligs in 1852, while he held the tack for Drumfork in 1863, so he evidently had a consistent interest in this type of work.

With the abolition of tolls in 1883, there was the question about what to do with the tollhouses. Many were sold off, but others were retained by the road authorities for use as tied houses for roadmen.

In the case of Helensburgh, the tollhouses at Ardencaple, established in 1856, and Drumfork were sold off, but Old Milligs Tollhouse was retained bythe Road Trustees.

A Valuation Roll from 1886 shows that its tenant was Duncan Morrison, a shepherd. Two years later, the tenant was Donegal-born Francis Boyle (37), described as a road surfaceman.

The Census of 1891 states that he was the head of household and lived with Glasgow-born wife Mary (30), and their children Daniel (12), Mary (10), Denis (7).

Daniel was born in Glasgow, but the other children were born in Helensburgh. Also listed was Daniel Boyle (15), a nephew, born in Rothesay, who was described as a labourer.

In addition, there were three lodgers, James Hancock (25), John McCullins (16), and John Boyle (58), all described as labourers.

Hancock and McCullins were natives of Armagh, while Boyle was listed as born in Donegal and might have been related to Francis.

Helensburgh directories listed Francis as tenant until 1935, but by 1937 the tenant is recorded as Miss Boyle, and she was still there in 1956.

By 1975, when the owner of the property was Strathclyde Regional Council, the tenant was Mary Boyle. If she was the daughter of Francis, it reveals a remarkable family link with the property over a long period.

Before the recent sale, renovation and expansion, the property had lain empty for quite some years. Now, while its front looks remarkably similar to old photos, the building has tripled in size.

Was the unpopular system of toll-paying roads effective in leading to better roads than what had gone before? It would appear that locally they were generally successful in that respect, at least initially.

In the New Statistical Account of Scotland, which gives a parish by parish account of the way of life as it was around 1840, the writer for Luss parish stated: “The turnpike roads to Helensburgh and Dumbarton are excellent.”

His counterpart for Arrochar parish commented: “The roads, with the exception of two miles on Loch Longside, are excellent. Bridges, with one exception, are in good repair.”

The writer for Row, later Rhu, parish mentions the turnpike road from Dumbarton to Arrochar, but he does not qualify this statement.

However, he does say of the new road over the Blackhill: “A new line of road from Helensburgh over the hill to Luss and Balloch Ferry affords an easy communication with these places.”

Taken together, these accounts paint a positive picture. On the other hand, the anonymous author of a guide to local walks, serialised in the Dumbarton Herald newspaper in 1857, makes some critical comments on the state of the road along the Gareloch.

He wrote: “Notwithstanding the number of turnpikes on it, the road from Row to Garelochhead is indifferently kept. At many points, two carriages could hardly pass.

“There are few walls or fences to protect the incautious traveller from the rocks on the shore. It is badly drained, and there is no footpath for pedestrians. In wet weather, the road is muddy to a depth of two to six inches. The scenery provides some compensation.”

It may be that with growing population and traffic, the type of roads then in use, even with income from tolls to fund maintenance, struggled to cope.

Although tolls were abolished in 1883, the administrative system of Road Trustees continued until 1889, when county councils were formed.

One of the main functions of the new bodies was that of road maintenance, and local authorities have continued to have a role ever since.

The various toll roads that once existed locally went on to form the backbone of the present-day road system, but what preceded them?

Prior to the 18th century, the only thoroughfares that existed in the county to the west of the River Leven would almost certainly have been classified today as tracks.

The first real road, in the modern sense, was the military road from Dumbarton to Inveraray via Loch Lomondside and the Rest and be Thankful.

Built between 1744-1750, this formed part of a network of military roads built after the Jacobite uprising of 1715 for strategic reasons, and it was instigated by General George Wade.

However, by the time this road was built, command had passed to Major Caulfield. He used soldiers for much of the work, but civilian contractors were called in as necessary, such as when major bridge works were required.

Unskilled civilian labour was also brought in before the Inveraray road was completed, at least on occasion. The mechanism under which this was done was through a system known as Statute Labour.

Provision for this scheme had been brought in during the 17th century, but it was not really used until the following century.

It entailed tenants, cottars and labourers having to attend for ‘road days’ on up to six occasions a year, to carry out unpaid work on roads and bridges.

The people with responsibility for managing this system were the Commissioners of Supply for the county, working in conjunction with Justices of the Peace. Both were drawn from the same body of people, essentially the landowning gentry of the county.

Statute Labour was deeply unpopular with those expected to turn out — quite possibly they would see the work as not being beneficial to themselves.

Conversely, the military were occasionally called in to help with building or maintenance work on non-military roads. This would have been organised through the Commissioners of Supply.

Under the Statute Labour system, work carried out was often considered to be of poor quality. In the absence of the civil engineering firms of today, the use of soldiers, paid for by the Commissioners of Supply, would seem to have made good sense.

No doubt motivated by acknowledgement of the inadequacy of Statute Labour, that system was abolished in Dunbartonshire in 1786, and replaced by a local tax.

This however was set at a very low level, and it generated a meagre income for road maintenance.

The Rosneath Peninsula roads were never made turnpike — sea transport may have prevailed — and road maintenance there was funded by the Statute Labour tax through much of the 19th century.

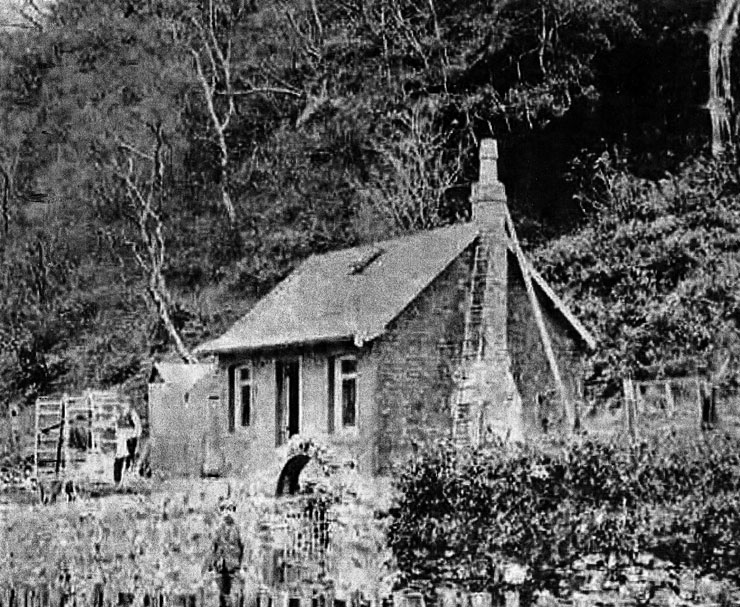

Maintenance of the Loch Lomondside military road (right: the Luss toll house as it is today) to Inveraray eventually passed to civilian control.

Maintenance of the Loch Lomondside military road (right: the Luss toll house as it is today) to Inveraray eventually passed to civilian control.

The Argyllshire section did so in 1814, and the Dunbartonshire section probably followed not long after implementation of the Dunbartonshire Act of 1807 conveniently cleared the way for the introduction of tolls on Loch Lomondside.

The 1760s building or upgrade of the road from Dumbarton to Row may have provided the catalyst for the local appearance of wheeled vehicles.

David Murray, the author of the book ‘Old Cardross’ in 1880, wrote: “Wheeled carts did not begin to be used until about 1763, and when they were introduced, crowds of people went to see such wonderful machines — they looked on with surprise, and returned with astonishment.”

However, it would seem that early promise suffered a setback, because Murray goes on to state: “The parish roads were so rough and so soft that, even by 1793, the farmers could not carry on improvements with horses and carts, save for a few weeks in the middle of summer, and sledges had to be used in many parts of the county to transport goods and produce.”

A significant part of the network of roads in the area was brought into being by private initiative, in particular through the work done on behalf of John Campbell, 5th Duke of Argyll, from 1770 until 1803.

Local author W.C.Maughan, in his 1893 book “Rosneath Past and Present”, quotes the inscription on a stone set into a roadside wall near Finnart Oil Terminal. It states: “This Road was made from The Castle of Rosneth To Tenne Claugh in the year 1777 by His Grace John, Duke of Argyle. Erected by Donald Fraser.”

Several other sources give the date of construction as 1787 as opposed to 1777. The stone has been cleaned, and possibly re-touched at least once over the years, so there may be a measure of doubt.

However the line of this road is essentially unchanged to the present time. Tenne Claugh is at Arrochar, where the new road joined the existing military road.

The same Duke also funded the road from Drumfork Ferry to Duchlage, south of Luss. Although there have been many changes since, the present roads from Crosskeys to Muirlands and to Arden could be claimed as guided by his pioneering work.

The minutes of a meeting of the Commissioners of Supply held in 1787 record that £270 had been spent on the road from Kirk of Row round the Gareloch, of which £242 had been provided by the 5th Duke of Argyll.

These roads were open to public use, but it could be argued the Duke was not necessarily building or improving these roads purely for the good of the community. Their presence meant that his three castles at Inveraray, Rosneath and Ardencaple now had a road link to one another, as well as to Dumbarton and the south.

g There are very few pictures of local toll houses, and it would be good to hear from anyone who has images of the Ardencaple or Drumfork toll houses.