PENINSULA residents are celebrating the 50th anniversary of the present Rosneath Primary School . . . but its history goes much further back than that.

Staff, parents and pupils — assisted by Cove Park’s Dawn Youll and artist Linda Florence — are busy organising appropriate events under the supervision of head teacher Mrs Emma McDermid.One of Linda’s aims is to produce an artwork which will reflect input from the children, including feedback from a recent question and answer session which included parents.

Also present at the session was local historian and Helensburgh Heritage Trust director Alistair McIntyre, who has undertaken considerable research on education in the area.

He says that Rosneath has had a school for a very long time because it was a parish from as far back as mediaeval times, with Rosneath Village, known as Clachan, at its centre.

At the heart of the mediaeval parish was the church, and one had been in existence at Rosneath from possibly as far back as the Dark Ages.

An evangelist known as Modan — which may well be derived from two words, “Mo Aiden”, or “My Aiden” — is traditionally understood to have settled there and established a religious centre in the remote past.

In support of this claim, in 1880 when work was being carried out in the grounds of the present St Modan’s Church, a carved stone was discovered buried deep underground.

Now kept inside the church, it has been dated by experts to around 800 AD, and is thought by many to commemorate Modan himself. Some people think that the site chosen by Modan might even have been considered sacred in pre-Christian times.

It is not known exactly when the first school at Rosneath was founded. In the mid-16th century, the religious reformer John Knox put forward a plan for a school in every parish, but this was not realised until many years after his death.

However Acts of the Scottish Parliament were passed in 1646 and 1696, making it a legal requirement for each parish to establish a school, to be paid for by local landowners.

Much of the parish of Rosneath was then owned by the Earls and later the Dukes of Argyll.

Although there may have been earlier teachers, the first definite name to emerge from the mists of time is that of Robert Monro, who was parish schoolmaster at Rosneath probably in the early 18th century and certainly before 1717.

The first teacher for whom an exact date can be given was John McNaughton, who became parochial schoolmaster on or shortly before 1800.

Although the Acts of the Scottish Parliament made a school in every parish a legal necessity, attendance at school was not compulsory.

Some parents may well have wished basic reading and writing skills to be imparted to their children, but for most families, the priority was to have children contributing to family income as soon as possible.

The majority of those children who did attend school probably would have done so only for a limited period.

The parish schools, although financed by the landowners, were actually under the control of the church, and schoolmasters — no lady teachers — were required to sign a document called the Confession of Faith.

This procedure was carried out in a bid to ensure that teachers did not have any views that were considered to be different from those of the established church.

The link between church and school at that time is further underlined by some additional roles that were expected of the schoolmaster, over and above his teaching duties.

He would be expected to serve as clerk to the Kirk Session, and lead the singing at church services. He might have additional duties, such as registering marriages and births, and was usually in charge of the Sunday School.

As recompense for all these duties, the master received payment, though the amounts were very small.

The parish schoolmaster was expected to put religious teaching at the heart of the curriculum. The pupils would all be taught to read and write, with the Bible and the Shorter Catechism — a set of questions and answers — as the main texts.

Discipline was strict, with the cane and the tawse, which is a leather strap, ready to hand. Hours were long, with lessons in some places starting as early as 6am.

The master was a key figure in the community, but this was not reflected in his income, which was very meagre considering all his responsibilities.

The salary had been set by the Acts of 1646 and 1696 at a minimum of 100 merks, and a maximum of 200 merks per annum which was a little over £11 sterling. These salaries were still in place more than a century later.

The Old Statistical Account of Scotland, drawn up in the 1790s, and made up of reports submitted by every parish minister, repeatedly refers to the inadequate salaries of teachers.

In many cases, schoolmasters had originally been educated with a career in the ministry in mind, but subsequently were unable to obtain a living in that capacity. The parish minister might thus have felt some special sympathy for his poorly-paid compatriot.

The schoolmaster’s total income at Rosneath, from all sources, was stated to be a little under £17 per annum in 1790.

Fees were at that time payable for instruction: at Rosneath, quarter fees for reading were one shilling, five pence in today’s money; for reading and writing, one shilling and sixpence; for reading, writing and arithmetic, two shillings. Latin incurred a higher fee.

The cost of living was of course very much lower at that time. Fees were payable by parents, but for those in very poor circumstances, parish funds were usually available to help out.

There was another totally unexpected and shocking source of income for schoolmasters in some places.

A widespread custom seems to have developed up and down the country whereby the master undertook to organise cockfights to take place at his school.

Defeated birds became the property of the master, destined for his cooking-pot.

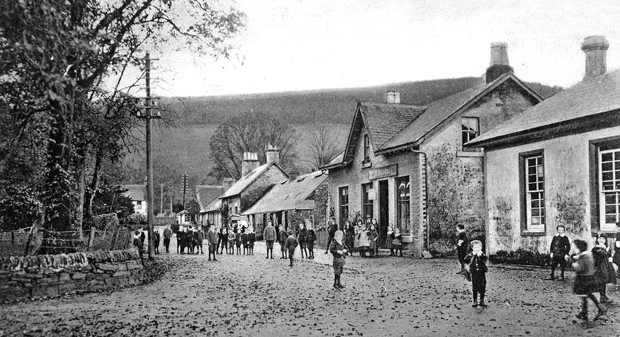

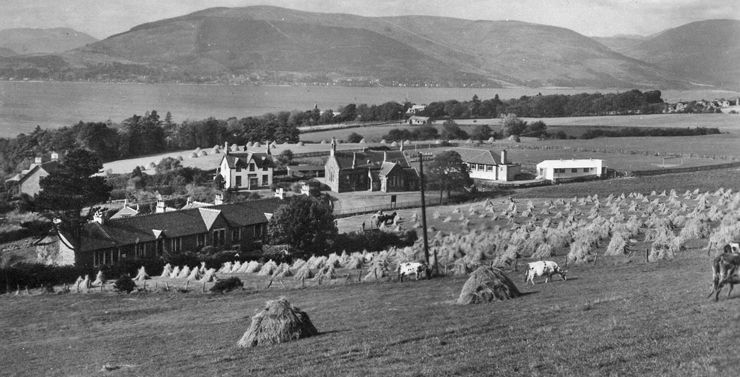

Rosneath School of 1835, pictured c.1905.

This unseemly and barbaric practice lingered on in some districts until the early 19th century, but no evidence has come to light to suggest that Rosneath School staged such events.

After 1803, there were modest increases in salary. A house was now also provided for the master and his family, but this could vary in suitability.

The master at Rosneath was probably better placed than many. His schoolhouse at the end of the Clachan was the upper floor of a substantial building with gable end to the then church, the school being on the ground floor.

While the existence of a parish school at Rosneath was welcome, travelling there daily from the more distant parts of the parish was simply not practicable, particularly for younger children, and especially in winter.

While education was not compulsory, there was undoubtedly a desire on the part of many parents for their children to receive at least some education.

This is hinted at by the coming into existence of schools over and above the parish school, especially from about 1700 onwards.

One example of such a school was at Letter, near Coulport. Recorded as being there in 1800, it was being taught by a John McFarlan.

Even though it was not the parish school, it would appear to have been established with the approval of the church. That is implied by the presence of McFarlan’s signature in the Confession of Faith document.

At one stage there was also a school at Rahane.

In 1808, John Graham became Rosneath parish schoolmaster and remained there until about 1820. In 1810, there were some 40 pupils attending, and his total income was £40.

In 1820, he was succeeded by John Dodds, who remained in post for fifty years until his death in 1870 and about whom much is known.

John Dodds was appointed in 1820 and was still in post when he died in 1870. An account of his service was written by a former pupil called John McEachern.

Born on the island of Mull in 1809, John McEachern and his family moved shortly after his birth to Glen Fruin, as his father was looking for work.

In 1821, they moved to Hill of Camsail, Rosneath, so John and other young family members attended Rosneath School.

He wrote: “Mr Dodds was an excellent teacher of Greek, Latin, French, German, mathematics, navigation, geometry, algebra, bookkeeping, drawing, and indeed all the qualifications necessary for a schoolmaster in any country parish in Scotland.

“He was a young man from the Borders, and taught in the best colleges in Scotland, with the most approved modes of pronunciation, and so on, the parish reaped much improvement by his school.

“He was a man of very civil, attractive manners, who took much pleasure in the improvement of his pupils, and in conjunction with the Rev Robert Story, the Parish minister, whose manse was in sight of the schoolhouse, every kind endeavour was used for the moral and spiritual training of the children.”

In 1830 the McEachern family emigrated to Prince Edward Island, Canada, but John evidently retained very favourable memories of his youthful years at Rosneath. His descendants still live on Prince Edward Island.

A different but equally favourable assessment of John Dodds comes from local historian W.C.Maughan in his 1893 book “Rosneath Past and Present”.

He wrote: “The late respected Mr John Dodds for fifty years taught the youth of the parish.

“Here assembled not only the sturdy, chubby-faced young children of the farmers and their labourers, but the families of the resident gentry were also glad to enjoy the privilege of the admirable tuition dispensed by Mr Dodds.

“In addition to the ordinary branches of knowledge imparted in the parish schools of Scotland, Mr Dodds taught the higher departments of mathematics, land-surveying and navigation, and gave competent instruction in French.

“Many of his pupils gained distinction in various walks of life, and remembered long, with kindly affection, the thorough grounding in education they acquired at the Rosneath School.

“Mr Dodds filled other posts in connection with the Parish and Church, and for twenty years was kind enough to act as Postmaster, upon inadequate remuneration.

“Dr James Dodds, the esteemed parish minister at Corstorphine, is a son of the worthy old schoolmaster of Rosneath.”

Few, if any, of the pupils would have received instruction in all the subjects he offered.

Relatively few parents would have been able to afford to keep their children at school for more than several years, though for those of special ability, financial support might have come from other quarters.

The Scots have traditionally prided themselves in their view that, while educational opportunity in the old days might have been far from perfect, there was at least a fighting chance that a really able boy — never a girl — of humble birth would be able to proceed to higher education.

Adults could also attend the school. John McEachern records that he returned to spend a winter at Dodds’s school after 1827, when he would have been aged 18 or over.

Indeed, when John lived in Glen Fruin, he mentions that when he first attended Abercrombie’s school there, it was in the company of his uncle, Neil Fletcher, who wished to better his education in arithmetic and book-keeping, Fletcher subsequently moved to Hill of Camsail, where he himself ran a school for a short time before the arrival of John Dodds.

It was in 1835, during the time of John Dodds’s tenure at Rosneath, that a new school was built at the foot of the Clachan. This was the school until the opening of the present building in 1967.

The school of 1835 thereafter served for some years as a community centre, but was then closed, becoming steadily more and more derelict.

Latterly owned by the Co-op, it received a great deal of criticism as an eyesore until its demolition in the last couple of years. It is a pity that a building so long associated with the education of local youth should at the end be regarded as a nuisance.

Another key source of information on the life and times of Rosneath Parish School is the New Statistical Account of Scotland. As with the Old Statistical Account, this was a parish-by parish account of the whole country, each entry written by the parish minister.

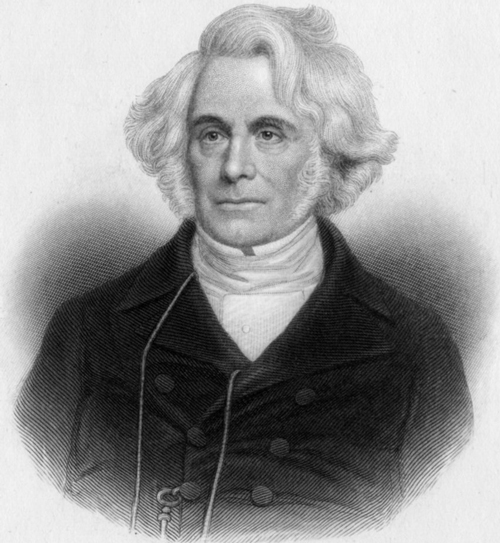

The section dealing with Rosneath Parish was written by the Rev Robert Story (right), and his report, drawn up in 1839, has much to say about the school.

The section dealing with Rosneath Parish was written by the Rev Robert Story (right), and his report, drawn up in 1839, has much to say about the school.

He wrote: “The different branches of a commercial and classical education are very efficiently taught by the parochial schoolmaster, and every day, the children under his care are instructed in the principles of religion.

“The average attendance may be rated at 70, although in the winter season, upwards of 100 are sometimes at school.

“The school was built a few years ago, a very handsome and commodious structure, superior to any in the county, and reflecting great credit at once upon the liberality and taste of the heritors (landowners).

“The schoolmaster’s house is at a little distance from it, immediately contigious to the Church, with accommodation much superior to what the statute provides for that class of most deserving men.

“The garden is much less than the legal dimensions, but he enjoys an allowance in lieu of that deficiency.

“The salary he receives is the maximum, with the fees 2/6d for reading, 3/- for writing, and 3/6d for arithmetic, and this may constitute an income of between £70 and £80 per annum.

“The only other school in the parish is at Knockderry. The teacher there has a salary of £35 a year, guaranteed to him by Mr Lorne Campbell, factor to His Grace the Duke of Argyll.

“Although the parents pay at the rate of 5/- per quarter for each child, the fees fall greatly short of the sum guaranteed, from the circumstance of the school commanding pupils from a very limited population, but whose distance from the parish school rendered its erection necessary, the expense of which was solely met by the Duke.

“Although less, it is built upon the same principle as the parochial school-house. Both houses are much more commodious than at present is needful, and it may be considered as anticipating any increase in population for a century to come.

“It may be stated that the people are universally anxious to have their children educated.

“All the natives of the parish, male and female, are taught at least to read and write, and although individuals from time to time are found that can do neither, they are generally natives of Argyll, servants to the different farmers.”

Numbers attending school were higher in winter than in summer. This was the normal state of affairs — in summer, children were expected to assist with labour-intensive work on the farm like hay-making and lifting potatoes.

John Dodds’s successor, William Stewart, also spent a long time in post, serving from 1870 until his retirement in 1905.

Rosneath School in 1905.

By that time, major changes in education were taking place. Just two years after Stewart took up his duties, the landmark Education (Scotland) Act of 1872 was passed.

Also known as Young’s Act, this remains the single most important date in the history of Scottish education, because, for the first time, education became compulsory for those aged between 5 and 13 years. There were, however, numerous exceptions and provisions for “half-time” attendance.

While education for all now had the force of law behind it, school fees were still chargeable to parents, although at a very moderate level. These were finally abolished in state schools in 1889.

The new legislation brought most schools, including the parish ones, under the state, thus replacing church control. The name changed to Rosneath Public School.

Each school under the new system was now administered by a school board, in this case the School Board of the Parish of Rosneath. But in practice, school administration was not so radically different, at least initially.

Members of school boards had to stand for election, but landowners and ministers, the people most closely involved with school management in the past, often put themselves forward as candidates.

The continuity between old and new was reinforced by William Stewart undertaking the role of clerk to Rosneath Kirk Session, in time-honoured fashion.

Under the system of parish schools, there may have been an element of external supervision, but with the school boards, there were established formal periodical inspections, a feature continued to this day.

Social changes followed the new regime. Female teachers began to be employed, though normally only as assistant teachers.

The only schools where a woman would be in charge would have been either very small, female only, or private.

Female teachers had to be unmarried or perhaps widowed — and any move towards a marital state meant instant dismissal.

Peaton Public School, which came into being in the wake of the 1872 Act and lasted until the early 1920’s, was mostly conducted by a lady teacher.

Peaton School and Church.

Other changes were sweeping across the country. The coming of the steamboat to the Clyde in 1812, and the later arrival of the railway, had made it much easier than before for people to move around.

At the same time, the rapid urbanisation of the Central Belt, and the emergence of a new class of well-off business and professional people, led to a growing demand around the Clyde Coast for plots of land on which to build villas.

Another potent factor was the realisation by landowners that here was an opportunity to raise much-needed revenue to support their own plans and ambitions.

Feuing of land for house-building at prime coastal locations was the outcome.

Large scale feuing began at Barremman in 1825, at Rhu in 1831, at Garelochhead in 1832, and at Shandon in 1834.

It was probably inevitable that feuing should also begin on the Duke of Argyll’s Rosneath Estate, which occupied the whole Peninsula, apart from the smaller estates of Peaton and Barremman.

It could be argued there was greater incentive here, thanks to the legacy of the profligate lifestyle of George Campbell, Marquis of Lorne, later the 6th Duke of Argyll.

He died in 1839, but his extravagance meant that Rosneath and other family estates remained in a perilous position for many years afterwards. Rosneath Estate was even put on the market in 1870 and 1873, but did not sell.

Feuing at Cove and Kilcreggan began in the 1840’s, and before long, a line of fine villas and mansions stretched for miles along the shores of Loch Long, enabling it to become a police burgh in 1865, and boast its own school in the next two years.

A long-serving teacher at Rosneath Public School was a typical example of the dominie of that era.

Although William Stewart was in post for 35 years, not so much has come to light about him as his predecessor John Dodds, but there a fascinating reference in the autobiography of a son of the manse at Rosneath, Charles Warr.

Charles was born in 1892, the second son of the Rev Alfred Warr, minister at Rosneath from 1887 until his death in 1916.

He sheds light on the world of William Stewart as a dedicated superintendent of the Sunday School.

He wrote: “The schoolmaster was one of the last of the old Scottish dominies.

“A scholarly, solemn, bearded man, impeccably dressed and of great dignity, his patriarchal appearance gained for him throughout the parish the irreverent sobriquet of ‘The Man o’ God’.

“The ‘Man o’ God had a dismal outlook on human affairs. One of the great truths he was wont to impress upon the urchins of the Sunday School was that they began to die the moment they were born.

“His choice of hymns reflected his attitude to life. But the children, being children, bawled these hymns with great enjoyment at the top of their voices. During prayers, the boys caused excessive hurt to the girls with their savage pinches.

“The Sunday School had its value, if only in the insistence on memorisation then in vogue.

“Every week, the children had to learn by heart some verses from the greater passages of the Bible, a portion of the Shorter Catechism, and also a number of verses from a metrical psalm or paraphrase. They had to learn the Commandments, the Beatitudes, the Creed, and the Lord’s Prayer.

“A generation was thus reared which carried out into life a certain cultural and religious endowment which never left them. There was not a child in the parish who did not attend Sunday School, and every lad and lass went to the Bible Class.”

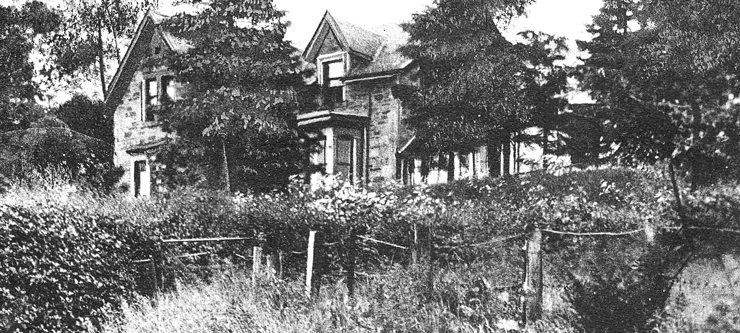

Charles did not have very much to say about Rosneath School itself, as he did not attend it for very long. When he came of school age, his father arranged for him to attend a private school at Hillside, Clynder.

Run by a Miss Campbell, Hillside was a boarding school for girls, but boys were also taken on a day basis up to age twelve.

Hillside, Clynder.

Miss Campbell wore dentures, and at the initial pep talk, Charles distinguished himself by asking her in all innocence: “How is it that you can move your teeth when I can’t?”

Around 1902 Miss Campbell had to close her school for a year for personal reasons, so there was a problem for Mr Warr about what to do about his son’s schooling.

By coincidence, the subject of Hillside cropped up a meeting at the manse with the Duke of Argyll and Lorne Campbell of Peaton. They agreed that for young Charles the closure was no bad thing, and that he would greatly benefit from at least a year at Rosneath School.

“So I found myself at the village school. I enjoyed it hugely,” he writes.

However something happened which was to change all that. One day, there was a visit to the manse by HRH Princess Louise, who was married to the Duke.

She embraced Charles, but as she did so, he inadvertently touched a boiling kettle. He had managed to pick up some fairly earthy terminology in the school playground, and made good use of several choice phrases after the scalding.

Once the Princess had made sure that Charles was none the worse, she laughed off the episode, but the minister — a member of the Rosneath School Board and later its chairman — was livid with fury.

Taking his son out of the room, he demanded to know where he had learned “those dreadful words”. So ended Charles’s time at the village school.

Badly wounded in the bloody and prolonged Battle of Ypres in the First World War, he went on to have a distinguished career as a churchman himself.

After William Stewart retired in 1905, the new head teacher was George Young. In his new colleague Miss B.Stewart, he would have found helpful continuity as she had served for some years under Mr Stewart to whom she may have been related.

Another Education Act in 1908 gave more powers to school boards. There was now provision through school attendance for medical and dental care, while food and clothing were to be available for the very needy.

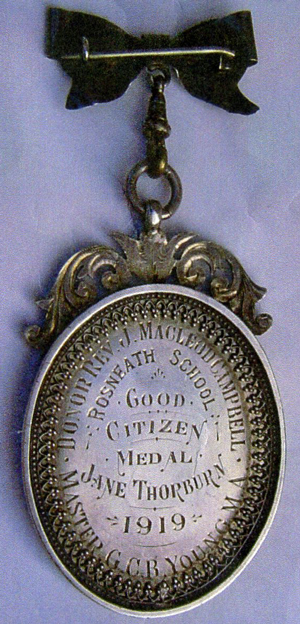

Good Citizenship medal won by Jane Thorburn in 1919.

These features were symptomatic of the more caring society that was emerging, but it also coincided with a time of increasing international tension.

Children on the Peninsula would have seen clear evidence of this through signs such as Portkil Fort and its mighty guns, dating from the early years of the new century — a statement of intent should any hostile warships enter the River Clyde.

The First World War wrought terrible death and injury among combatants, with communities up and down the country suffering. Rosneath was no exception, and a number of former pupils serving with the armed forces were killed or injured.

Yet the Second World War was to have significantly greater overall impact locally than the earlier conflict.

As the First World War drew to a close, further educational change came with the passage of the Education (Scotland) Act, 1918. The 538 School Boards were replaced by 38 Education Authorities, one of which was Dunbartonshire.

Many people wanted education brought under the control of the county councils, but political pressure meant this did not happen until fresh legislation in 1928.

There was a second tier of administration, with schools like Rosneath coming under the Helensburgh District School Management Committee, which reported to the Dunbartonshire Education Authority.

The Roman Catholic and Episcopalian schools, previously under separate control, now came into the state system.

The new legislation had a clause for raising the school leaving age to 15 years, but this was not achieved until fresh legislation in 1945.

For those of sufficient ability and the necessary parental support, the possibility of progress to higher education had long been available, helped by the existence of grants and endowments.

Any such ambition had been enhanced in 1888, with the introduction of the Scottish Leaving Certificate. This provided a tangible target and stepping stone for those aspiring to proceed along the academic road.

The certificate normally entailed studying at certain schools which offered more advanced courses. For many children, however, their formal education would have begun and ended at Rosneath School.

Dunbartonshire Education Authority in 1921 advocated the transfer of pupils from schools like Rosneath to one in Helensburgh after reaching the age of 12 years.

This might have provided a stimulus for those considering a move to more advanced study, but the idea met with opposition. It was not until 1945 that a system of primary and secondary schools came into being.

The switch of education from Education Authority to County Council control in 1928 continued with the second tier of administration. Helensburgh District School Management Committee had 13 schools under its control.

The early 1920s saw the appointment of a new headmaster at Rosneath, Matthew Cross. It was not long before he too was serving as clerk to Rosneath Kirk Session.

His assistant was still Miss Stewart, who served under three different head teachers. By this time, some very well qualified women were coming through the educational system, although they were still finding it virtually impossible to obtain senior teaching posts.

In the mid 1920s, Mr Cross was replaced by George Glennie, who was still in post at the onset of the Second World War.

This conflict had an enormous impact in the area, not so much from direct death and destruction, but through the setting up of a vast military infrastructure.

With the return of peace, a good deal of this was retained, and in several cases greatly expanded, with Coulport and Faslane two prime examples.

During the war, life at school had to go on with the usual routines augmented by black-out and gas-mask training, coupled with the presence of child evacuees from the big towns and cities.

Just months before the outbreak of war, an historic link with the past was broken, with the death of Princess Louise in 1939.

Her consort, the 9th Duke of Argyll, had predeceased her in 1914, and since then, Rosneath Estate had been in the hands of trustees.

The death of the Princess effectively heralded the sale of the Estate, which had been in the Argyll family since the 15th century. By 1943, the Estate had been sold off — symbolic of the end of one era and the dawn of another.

The end of the war coincided with another key piece of legislation, the Education (Scotland) Act, 1945. Pupils as well as staff faced big changes as a result.

The school leaving age was finally raised to 15, this being coupled with an 11+ streaming exam, and the creation of separate schools for nursery, primary and secondary education.

Rosneath Public School now became Rosneath Primary School, and after seven years of primary education, pupils moved to secondary education in Helensburgh or Dumbarton.

Kilcreggan, a Free Church school, erected by Lorne Campbell and roughly similar in size to Rosneath, operated for a few years as a junior secondary school.

Another big post-war change was a climate in which female teachers could realise their potential. By the 1950s, Rosneath had its first female head teacher, Mrs Elizabeth McLaughlin or Slorach. Other local schools had similar breakthroughs.

In the Third Statistical Account of Scotland the Rev Dr Cameron Dinwoodie wrote: “Rosneath is a three-teacher school with a roll just under 80.

“All secondary pupils from the two schools at Rosneath and Kilcreggan are taken by bus to Hermitage Secondary School in Helensburgh.”

Mrs McLaughlin or Slorach was not only a dedicated teacher, but also very community-minded. In 1960, she was one of the driving forces behind the formation of a charitable body called the Rosneath Anvil Trust.

This followed an earlier example in the wake of the break-up of Rosneath Estate in the 1940s, when local people set up the Rosneath Clachan Trust to buy and preserve the old cottages making up the Clachan, which were then made over to the tenants.

The oldest building in the Clachan was thought to be the smiddy — hence the name of the new trust.

A considerable capital sum of money was put together, then invested. The interest has allowed donations to local good causes ever since.

The last two years have seen sizeable donations made to causes including the purchase of a defibrillator, the Peninsula Churches Together Holiday Club, and Rosneath Highland Games.

By the 1960s, the population was expanding greatly, and the need for a new school became paramount. It was decided that the ideal location was the site of the former mansion known as Clachan House, gutted by fire in 1962.

The new school was officially opened on October 6 1967 by James Roy, Provost of the Burgh of Cove and Kilcreggan.

In his speech, he referred to the new facility as “one to be proud of”. The Head Teacher, Miss Elizabeth McKay, a native of Rosneath, expressed her joy at the new School, and said she had admired it from Clachan Hill, and from the Gareloch.

At present, she had seven colleagues, along with two visiting teachers. There were at present 106 pupils on the roll.

This was an era of further change: the 11+ exam had been abolished shortly before, and around this time, many primary schools were dispensing with the annual prize-giving ceremony — months before the opening of the new Rosneath School, Hermitage Primary had announced the cessation of the practice.

New ideas and teaching methods were also being brought in, and the succeeding decades witnessed many more changes.

The year 1975 saw yet another change in the administration of education, the abolition of county councils, and their replacement by a new two-tier system, cconsisting of regional councils and district councils.

Education was a function of the regional councils, and so Rosneath, and the other state schools in the area, came under the massive Strathclyde Regional Council.

The district council for the area, Dumbarton District Council, did not have education as a core function.

By this time, influences that had already been in existence for quite some time, were assuming ever greater importance.

The ever-increasing complexity of educational planning and delivery was placing more and more responsibility on teaching staff, with the consequent need for administrative support.

The use of technology in schools for use in teaching and administration was also on the increase, including the use of programmes broadcast by radio, this dating from the 1940s and 1950s, followed by TV-beamed programmes.

By the early 1980s, schools were also becoming involved with the use of computers.

A ground-breaking application of the new technology came about in 1986, with the BBC Domesday Project. Schools from all over the country were encouraged to submit information, and the result has been an invaluable historical record.

Rosneath School was one of those participating. Miss McKay was still the Head Teacher at Rosneath, and following the opening of the new school in 1967, the roll had risen at one stage to a peak of 259 and there were currently some 191 children on the roll.

The Head Teacher was supported by seven classroom colleagues, four of whom commuted from Helensburgh, along with one part-time remedial teacher. The former school was in use as a community centre.

The 1990s witnessed the demise of the regional and district councils, and their replacement by single-tier local authorities in 1996.

Another major change at this time was the transfer of part of the former Dumbarton district, Helensburgh and district, to the newly-formed Argyll and Bute Council. Education was, and remains, a key function of this unitary body.

The school roll at Rosneath in the 1990s was somewhat lower than had been the case in the 70s and 80s — 1992, 170; 1993, 148; 1994, 152.

This reduction was also seen in other schools in the area, and probably reflected a national trend of smaller families.

By the dawn of the new Millenium, it was becoming clear that changes in information technology and communications were affecting not only education, but society generally, especially through developments such as personal computers, the World Wide Web, and the Internet.

Information of all kinds could now readily be had with the mere press of a button. As a result, a good deal of information about Rosneath School can readily accessed today by almost anyone, thanks to the Internet.

Thus, for example, the findings of an HMI inspection, carried out in 2003, confirms the excellent work being done there.

It stated: “With the effective leadership of the head teacher, and the strong commitment and teamwork of all staff the school had improved in key areas of its work. There continues to be a very positive ethos within the school.

“The head teacher and the staff had worked hard to establish good relationships with pupils. The school placed strong emphasis on partnership with parents.

“Classroom assistants, administrative, janitorial and catering staff are actively involved with the life of the school, and contribute effectively to the school's positive behaviour policy.”

This example is very useful in demonstrating both the complex demands of modern educational provision and the key part played by those other than teaching staff in the life of the modern school.

Even very recently-released information may be similarly obtained. For example, an article, dated June 26 2017, carried the headline “Rosneath Primary goes from strength to strength” described how the school had benefited from the Government's Attainment Scotland Fund launched 18 months before.

It was one of 57 schools across the country taking part, and the scheme had led to significant improvements in the learning process, including reading and literacy.

The school has developed and prospered, embracing the dramatic changes in technology and media and continuing a tradition of excellence.

Other Peninsula schools

Letter Farm

Local historian W.C.Maughan provides some interesting glimpses into past school life in his 1897 book “Annals of Garelochside”.

At some stage he had spoken to a Mrs Marquis, a “venerable native of Rosneath”, whose father had actually built the school at Letter Farm — presumably he was the tenant farmer there.

He wrote: “It was a small thatched house, with four small windows and a hole in the roof to serve for a chimney, where the schoolmaster, John Chalmers, taught the children.

“The master came for a fixed period and stayed with one of the farmers, getting his board and very small fees for renumeration.”

Barbour Farm

This school is also referred to by Maughan, who wrote: “On the Barbour Farm there was a similar old school, even humbler in its furnishings than the school at Letter.

“The boys and the master, Andrew McFarlane, who had lost an arm, used to sit round the peat fire, piled up in the middle of the floor, on stormy winter days.

“The seats were one or two planks placed on lumps of turf, and there was a long form at one end at which the boys wrote, each scholar being expected to bring a contribution every day in the shape of a large peat for the common good.

“Later on there was rather an original character. James Campbell, from the Ardentinny side, who acted as teacher, and he would enjoy his pipe while imparting instruction.

“One of his pupils remembered how the master, when finished, would pass the pipe to the nearest boy, from who it circulated through the class.”

All this suggests a very homely atmosphere, but Maughan counters that perception by adding that “the good old instrument of flagellation, known as the tawse, was in frequent use, for the former school of teachers had implicit confidence in this gentle art of persuasion.”

Blairnachtra Farm

Maughan relates that this school, on the site of the former Blairnachtra Farm, was in use around 1834.

He wrote: “It was a well-built, small, stone house beside the Dhualt burn, erected by the Duke of Argyll and his tenants for the benefit of children on that side of the Peninsula, and frequently used as a place of public worship by the Rev Robert Story, before the church at Craigrownie was built.”

Kilcreggan

Sunnyside Cottages and Kilcreggan School.

From a modern perspective, it might seem unexpected that the Chamberlain, and implicitly the Duke, should look favourably upon the Free Church, since the matter of patronage was one of the key issues in the Disruption of 1843.

The 1712 Act of Patronage meant that the landowner had the ultimate say in the selection of parish ministers, and this sometimes led to friction with congregations.

The Free Church believed that the congregation should have the ultimate power in this respect.