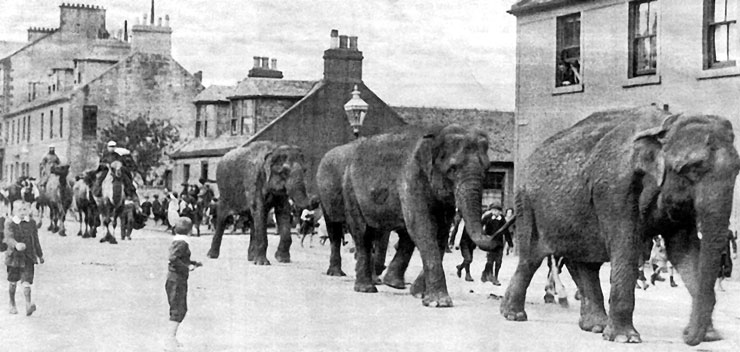

MANY a long-time Helensburgh resident will remember elephants parading along East Princes Street . . . an unusual spectacle heralding the arrival in the burgh of a circus.

The travelling circus had an association with Helensburgh going back over many years, and quite a number of the most prominent of them visited the town.

The most famous of all Victorian circuses, that of Lord George Sanger (left), came to the town on a number of occasions.

Local historian and Helensburgh Heritage Trust director Alistair McIntyre is definitely a circus fan, and he has researched the history of circus visits over the years, and their pros and cons.

He says: “The circus: what a world of excitement and glamour is conjured up by those simple words! Who has never been mesmerised by the showmanship of the ringmaster, with his or her scarlet coat, top hat and whip?

“Who has not felt the nail-biting tension of the glittering artistes on the high trapeze, and who has never rolled over with laughter at the antics of the clowns?

“But at the same time, the magic of the circus was for some time tempered by one issue — the presence of wild animals in the show.”

The earliest forms of circus to perform in the town were those associated with the two annual fairs that took place in the formative years of the burgh.

The book “A Nonagenarian’s Reminiscences”, written by Donald McLeod in 1883, gives a glimpse of those far-off days.

“The two annual fairs did a good stroke of business, in the way of selling cattle and feeing servants, and they were also occasions of festivity,” he wrote.

“Travelling showmen, with their human monstrosities and other attractions, jugglers, acrobats, minstrels, tight-rope dancers and others of like kidney, conjoined with gingerbread dealers and candymen.”

Little is known about these people as they were small-scale performers, and they remain anonymous and unrecorded apart from their local fame.

The first British circus properly identifiable with the owner’s name was that of Philip Astley, dating from the 1770s, while in Scotland minister’s son Thomas Ord began his show in 1804 with a single donkey.

As far as Helensburgh is concerned, Lord George Sanger’s circus is the first about which much is known. As far back as 1854, Sanger had spent five weeks in Glasgow and had visited large towns like Greenock.

Doubtless his shows would have been patronised by numbers of people from Helensburgh. However his first known appearances in the town itself were much later.

Born in 1825 at Newbury, Berkshire, George was the sixth of ten children born to a couple who ran their own small travelling show. In 1848, George, along with elder brother John, set up their own little circus, initially a juggling booth and trained canaries and mice.

Young George possessed an enormous aptitude for showmanship and business acumen, and along with John soon built up a large and stylish circus.

However, the first known visits to Helensburgh date from the late 1880s, by which time the brothers had gone their separate ways, and it was George Sanger’s circus that came to the town.

It was around this time that the designation ‘Lord’ George came about.

The story goes that in 1887, when Buffalo Bill (William F. Cody) came to Britain with his gargantuan Wild West Show, he discovered that Sanger’s circus had incorporated elements of what Buffalo Bill considered infringements of his own show.

The circus in the United States had once used British circus as a template, but over time the tables had been turned, with the circus here staging the likes of fights between cowboys and Indians. Buffalo Bill took the matter to court, and he prevailed.

In order to restore injured pride, Sanger decided to award himself a lordship. In fact, this was not quite as outrageous as it might have seemed as he was already known as “Gentleman George” by his circus peers, while his own father referred to him as “His Lordship” because of his assured bearing, and smart mode of dressing.

Buffalo Bill’s show never made it to Helensburgh, though it did feature at Dumbarton on July 29 1904, and was based for the whole of the winter of 1891-92 in Glasgow.

When Sanger’s circus came to Helensburgh in June 1893, the Helensburgh and Gareloch Times newspaper reported: “Lord George Sanger, the world-renowned showman, has brought along his stupendous exhibition, comprising hippodrome, circus and menagerie, an occasion of the greatest importance to all classes of our community.

“He appeared in the town very early yesterday. Notwithstanding, the progress of the cavalcade towards Hermitage Park, where it has been located on all previous visits, was watched with the greatest of interest.

“The magnificent marquee has accommodation for 20,000 people, and the fixing up of it is no easy matter. After this and other preparations had been made, the inhabitants witnessed an open-air procession when the gigantic resources of the establishment were displayed to greatest advantage.

“An afternoon matinee attracted a very large attendance as did the evening show. The programme had many varied and interesting features.

“Especially noteworthy were ‘The Horse of the World’, and ‘The Beautiful Georgina’. Lord George is always sure of a hearty welcome.”

The distances covered between destinations might be as little as five miles, but they could be as much as 20 miles. On arrival, breakfast would be taken before the task of setting up.

On Sanger’s visit of 1893, the local progression was Alexandria, Monday June 26; Helensburgh, Tuesday June 27; Dumbarton, Wednesday June 28.

Over the course of a season running from February to November, his circus would typically cover 2,000 miles, with over 200 places visited.

It all made for a hard, hard life for both humans and animals.

On average, Scotland might be included in the itinerary about every third year. Horses provided the basic motive power, though exceptionally a train might be used to take the circus to the starting point for the new season.

The journey on the road was quite distinct from the procession that took place once the necessary infrastructure was in place. This provided townspeople with a great spectacle, while for the circus, it served as first-class advance publicity for what was to come.

Leading the procession was the bandwagon, the music from which could be heard up to half a mile away. It would be pulled by at least six horses, though it could feature as many as 20.

Then came a line of artistes, 20 cages with wild animals, a line of costumed riders, who could be lancers, or cowboys and Indians, then the Asian Indian tableau, then the elephants, more riders, the camels, and finally, the Queen’s tableau and the King’s tableau, attended by a Life Guard, with glittering cuirass and white-plumed helmet.

At this time, Sanger’s profit was estimated at some £14,000 per season.

A highlight of Lord George’s career came in 1898, when, by Royal command, he was asked to bring his circus to Balmoral Castle for a performance before Her Majesty on June 17 1898.

Afterwards, he had an audience with Queen Victoria, when Her Majesty joked with him about his title. One of his treasured possessions was a large silver cup presented to him by the Prince and Princess of Wales.

In 1905, he sold off his circus effects and retired to the circus farm at East Finchley. London.

Lord George’s life came to a sudden and violent end, at the age of 86 years, when, on November 28 1911, he was attacked and killed in his own home.

An account which appeared in the ‘Evening Telegraph’ shortly after his death stated: “Lord George Sanger was attacked by a young man employed on the farm. His skull was fractured, and he died later.

“The full circumstances were never fully understood, but it is believed that the young man, Herbert Cooper, employed by Sanger, had been suspected of stealing from the house. Sanger had heatedly confronted him, but the matter was not referred to the police.

“Cooper went away, but later returned to the house in a deranged state. He attacked two men before turning to Sanger and striking him on the head with an axe, caused fatal injuries.

“Cooper then ran off, but he was found dead by a railway track four days later, and it was concluded he had committed suicide.

“At the inquest into both deaths, the coroner found that Sanger had died of ‘wilful murder’ by the hand of Cooper, who then committed suicide.”

It was a truly sorry end for the man who was described as “The Prince of Showmen”.

The 1890s also saw a visit to Helensburgh by the well-known Bostock’s menagerie. The origins of the menagerie go back to the ancient world, but in more recent times it became the province of European royalty, who liked to entertain important visitors with staged fights between animals.

The earliest travelling menageries in Britain dated from the 1700s, and in 1748, one of them came to Glasgow. Most of the bigger circuses incorporated a menagerie, while Bostock’s menagerie featured some circus-type acts, such as lion tamers and others.

The death of Lord George was by no means the end of the Sanger story.

His brother and erstwhile partner, John, had a son, also John, and it was he who now took on his late uncle’s mantle.

He billed himself as Lord John Sanger, and it was under this banner that Sanger’s circus came to Helensburgh before and after the First World War.

Lord John’s circus seems to have been as successful as that of his uncle George, and he came back again shortly before the outbreak of war in 1914, then twice after the First World War, in 1919 and 1924.

The war had a devastating impact on the world of the circus, as with all walks of life, and many of the best artistes and performers gave their lives in the conflict. It is also believed that some of the animals had to be put down.

Afterwards, however, Sanger’s circus was able to regroup, and one of the star attractions was the clown ‘Pimpo’, real name James Freeman.

He is regarded as one of the greats of all time, and for many people, his appearance was the highlight of the show.

Rejected for military service in 1914, his agility and versatility were legendary, as he was as much at home with the artistes on the flying trapeze as on the sawdust.

A spectator recalled: “The one figure who remains distinctly in my memory is Pimpo the clown.

“I can see him now, sitting in a motor car, strapped to an elephant’s back, giving the hooter spasmodic blasts, while he raucously hailed the ringmaster, his diminutive figure clad in oversized dress-suit, a mass of ginger hair sprouting from the top of his head, and an enormous bow-tie.”

Pimpo (left) was married to Victoria Sanger, great-great-grand-daughter of Lord George. Lord John was married to Rebecca Pinder, a member of another great circus family, while younger brother James was wed to Babs Pinder.

Alistair McIntyre says that the circus world is a very tight-knit one, and there were many marriages across the leading families.

Sanger’s 1919 visit was reported by the Helensburgh and Gareloch Times of July 16 which chronicled some of the behind the scenes efforts needed to keep the show on the road.

“Country districts are usually scattered, and to let them know Sanger is coming is no easy matter,” the paper reported.

“About five weeks ahead of the circus, an advance manager is sent out. He is followed about two weeks later by a number of bill-posters.

“This is very costly, and printing alone can cost £240 a month, which with extra bills and posters, along with payment for sites to display them, can cost another £260. With incidentals, the monthly bill can be £680.

“The salaries of artistes and performers come to about £7,000 per season, with wardrobe expenses some £1,800.

“The 320 animals cost a pretty penny in food alone. Each day, the bigger animals consume 100 lbs of butcher meat, costing £5 daily, or £1,800 a year.

“The enormous quantity of hay needed is 800 tons, and in the course of the year, 3,650 quarters of oats are used, as are 150 tons of chaff. The enormous tent is another costly item.”

Another matter was the essential business of obtaining permission from the relevant authorities well in advance, and payment of the associated charges.

The year after the 1919 visit to Helensburgh, Sanger’s circus was the scene of a terrible fire while at Taunton in Somerset.

The afternoon performance was in full swing, and people laughed as they watched Pimpo engage in a boxing match with a pseudo army sergeant, Leslie Sanger. Suddenly there was a scream of “fire!”.

Someone who was present claimed that the big top was completely consumed by fire in under five minutes. There were only two entrances, and five people lost their lives, while twenty were injured.

There were some heroics by circus staff as well as by others. The verdict at the coroner’s inquest was death by misadventure, with the fire probably being started by someone carelessly discarding either a lit match or a cigarette.

Despite this awful tragedy, Sanger’s circus and menagerie was back in Helensburgh in 1924. Lord John died in 1929, but Sanger’s circus carried on until 1941.

The Second World War was, if anything, more difficult for the circus world than the Great War, as there were labour and petrol shortages, along with rationing of food and other restrictions.

James Sanger said: “I’m afraid it’s all over. The Blackout beat us.”

Helensburgh does not seem to have been visited by many of the great circuses during the 1930s, and there can be little doubt that factors like the Great Depression would have taken their toll. However, there were still opportunities for circus-goers.

For example, adverts appeared in the Helensburgh and Gareloch Times in 1935 and 1938 on behalf of Bertram Mills circus for performances in Greenock.

The London and North Eastern Railway Company ran additional steamers from Helensburgh, Craigendoran and the Gareloch to cope with the large numbers wishing to go to the circus.

As with a number of circus owners, Bertram Mills gravitated towards circus life on account of his great love of horses. In the First World War he had been an army captain, charged with supplying fodder for horses.

When he set up his circus, he had no background in that field, but soon showed great flair and aptitude. Indeed, one circus writer stated that it was he who was the salvation of the post-war circus, offering a show that was as good as any on the Continent.

His was a very large concern, and two trains were chartered to move the show from one place to another.

Each show featured 21 acts on average, with the band playing around 120 snatches of music. The bandmaster took his cue from the movement of the horses, not the other way round.

It was particularly appropriate for Bertram Mills circus to come to Greenock, as the Gourock Ropeworks had supplied not only his big top, but the smaller tents and ropes as well. Henry Bell’s “Comet”, with its large squaresail, was also rigged by the same firm.

A big top might need a mind-boggling 4,500 square yards of heavy cloth, weighing in at around 4 tons. Gourock Ropeworks was one of the few firms capable of providing what was required.

After World War Two there was something of a renaissance, and Helensburgh Town Council received quite a number of applications from circuses wishing to visit.

One was Tommy Pinder’s New International Circus, which had intended to come in 1959, but at the last moment, the town council withdrew permission on the grounds that East King Street Public Park required renovation.

But when Pinder’s tried again in 1960, they were successful, it being described as their first visit for many years.

Pinder’s circus claims to be the oldest British circus still in existence, as it dates back to Thomas Ord, the son of a minister, who was expected to study medicine. Thomas, who was born in 1784, had other ideas, however, and took up an apprenticeship in horsemanship.

According to Thomas Ord’s grand-daughter, his master treated him very harshly, but in the event, the pupil exceeded all expectations and passed out as a star performer.

Thomas set up his little travelling circus in 1804, allegedly with a single donkey, but he soon built up an impressive show, touring all over the British Isles, and reaching as far north as the Orkneys, though it is not known if he visited Helensburgh.

At the age of 75, shortly before his death in 1859, Ord (right) was still performing one of his trademark acts, standing upright on a horse galloping round the ring at full speed — a remarkable achievement, but perhaps worthy of a man known as the Father of the Circus in Scotland.

Ord based himself at Biggar, and was buried there, his headstone describing him simply as “Equestrian”.

Selina, one of Ord’s daughters, married Edwin Pinder in 1861. Pinder’s circus was founded by two of Edwin’s uncles in 1854, and when they decided to move their show to the Continent, the mantle of running Pinder’s British circus fell upon Edwin and his bride.

The young couple developed a show, the status of which may be judged by the fact that they were asked to perform before Queen Victoria on no less than three occasions. As a result it became known as Ord-Pinder’s Royal Circus.

Over time, though, another branch of the family set up its own circus, and it was Tommy Pinder’s New International Circus that visited East King Street Park in Helensburgh. There was a return visit the following year.

Following the 1960 performance in Helensburgh, the next stop was Garelochhead, followed by Arrochar, and then Kinlochleven.

Local villages could expect to host few of the big names, but smaller shows visited from time to time. At Garelochhead, older residents recalled several sites being used, one near the bottom of Station Road, another at the site now occupied by the Fire Station.

Tommy Pinder’s circus was among the first to introduce motorised transport, though for a number of years they continued to use horses as well. By the 1960 visit to Helensburgh, however, horse-drawn transport would have been very much a thing of the past.

Circuses liked to refresh their shows from one year to the next, and one factor which expedited this was seasonal movement of performers from one circus to another.

The “Scottish Samson” — real name William Beattie, from Blantyre — is a good example.

With Fossett’s circus in the late 1940s, he performed with Rosaire’s circus in the early 1950s, Pinder’s circus in 1956, Joe Gandey’s in 1957, Mrs Pinder’s Royal No.1 circus in 1958, Tommy Pinder’s circus in 1959 and 1960, and so on.

The circumstances surrounding the end of Tommy Pinder’s circus was revealed by two of his sisters, Kathleen and Rosetta, when they were interviewed by a national newspaper in 1992.

Their circus was very much a family affair. They themselves, along with sister Lily May, had been bareback horse riders, while Edward, their brother, was the ringmaster.

Two other brothers, William and George, were the clowns, while brother Tommy, after whom the circus was named, as a lion tamer.

A major setback occurred in 1974 when Tommy suffered a slipped disc. It was realised that they were all getting older, and it was decided to call it a day.

Despite the rigours and dangers of such a demanding life, a surprising number of circus people lived to a very ripe old age — Rosetta died in 1998 aged 95, while Kathleen, who died in 2010, was in her 100th year.

Another famous circus which beat a path to Helensburgh was Sir Robert Fossett’s circus.

The title ‘Sir’ was self-awarded, legend having it that this was done to counterbalance the elevated status enjoyed by ‘Lord’ George Sanger.

Although ‘Sir’ Robert died in 1922, that designation was retained as the name of the circus.

The Fossett circus boasts a long pedigree. Although smaller than the likes of Bertram Mills and Billy’s Smart’s, it outlived them, surviving two World Wars and the reign of five monarchs.

Some accounts trace their origins to the Highlands. However Robert Fossett and his bride Emma Yelding set up their circus in London in 1852, and it was their son, also Robert, who distinguished himself with the title ‘Sir’.

The Fossetts were related to another well-known circus family, the Pinders.

The Fossetts were famous for their unusual combination of red hair and blue eyes — in the 1930s, a noted equestrian act featured eight red-headed riders astride a single horse.

A family member, Jacko Fossett, became one of the most celebrated clowns of the last hundred years, appearing with just about every major circus in Britain and Europe.

Fossett’s circus visited Helensburgh on a number of occasions, but the first reported local performance took place in 1970 in East King Street Park, by then the usual location for circuses.

Many circuses only came for a single day, but in this case, the application was for three days.

One audience member wrote: “Tigers, spinning trapeze artistes, majestic horses, whip-cracking cowboys, exploding clown cars, plate spinning, knife-throwing, and even a human cannonball, all passed in an amazing kaleidoscopic succession.

“But it was the sight of five massive elephants thundering into the ring and being put through their paces by Robert Fossett and Goldie, that I will never forget, Still, to this day, it was one of the best circus acts I have ever seen.”

Audiences also found a particular appeal in what they perceived as exotic acts and performers. Buffalo Bill’s American Indians were a source of great fascination.

Another circusgoer recalled an act from Fossett’s circus: “The great attraction was a troupe of Arab acrobats: how we gasped at the speed and the furious antics of these strange men!”

The high regard in which Fossett’s circus was held is exemplified by their association with big names like John Lennon and the Rolling Stones, while one of their elephants, ‘Aga’, starred in the film “Elephant Boy”.

Although Fossett’s circus no longer exists in Britain, it continues to thrive in Ireland. In 1918, a family member, Edward, made up his mind to join a circus in the Emerald Isle.

Four years later, he married Mona Powell, who came from a leading circus family, and it is their descendants who have kept the Fossett flag flying to the present time. In 2007, Fossett’s circus won the accolade of National Circus of Ireland.

In the early 1960s, there were visits to Helensburgh by Major Russell’s circus and Broncho Bill’s circus, but very little is known about either.

The last of the well-known travelling circuses to perform in Helensburgh were that of the Roberts Brothers, and its successor, Bobby Roberts Super Circus. In 1977 this was the last circus to perform in Helensburgh.

The Roberts story can be traced back to Mary Fossett, a daughter of Sir Robert Fossett, who married Paul Otto, a Belgium acrobat and clown.

Their sons, Robert (Bobby) and Tommy, married in their turn, and the two young couples came together as a riding troupe.

By this time, however, the Second World War was raging, and it was decided that their surname “Otto” sounded too Germanic. In consequence, they adopted the surname Roberts, and it became the Roberts Brothers Circus.

The Roberts circus applied to Helensburgh Town Council in 1964 for a staging of their show.

By that time, the council was becoming increasingly particular about such shows, but when it was revealed that the applicants were members of the Circus Proprietors’ Association, a body that helped ensure high standards, this went in their favour.

A parade of elephants was staged, starting from Helensburgh Central Station and ending at East King Street Park. This was the beginning of a relationship with Helensburgh and district that was to last for some years.

The last elephant parade to take place in the town was that of Roberts Brothers in 1977.

However, they did continue to visit the area long after that occasion, when the venue was switched to Westerhill Farm, between Cardross and Dumbarton.

Many will recall their massive big top, easily seen from the main road and from the railway, until the final appearance in 2011.

Bobby and Tommy Roberts ended their partnership in 1982, and from then the circus went under the name of Bobby Roberts circus. Eventually, when Bobby Roberts retired, it was his son, also Bobby, and his wife, Moira Rettie, took over the reins.

At some stage, perhaps even before the young couple took over, the show became known as Bobby Roberts Super Circus.

They did well to thrive, as by the later 20th century, many of the big names, like Bertram Mills and Bobby Smarts, had fallen by the wayside, with many blaming television as a factor in their demise.

The Roberts circus earned many accolades over the years. There were several performances before Her Majesty The Queen. In the early 1980s, their circus was named “Circus World Champions” by a BBC TV programme.

For many years, it was their circus that performed at the much-loved Kelvin Hall Christmas Carnival and Circus, and later, at the SECC. Quite possibly, this will be the circus that many local people best remember.

The circus was renowned for the variety of its animal acts, which included bears, lions, tigers, leopards, chimpanzees and elephants, in addition to horses, ponies and dogs.

In 1998, Bobby Roberts Super Circus was called “Best Circus in Britain with Animals”.

Ultimately, however, this emphasis on animal acts appears to have been a leading factor in their demise.

Animal acts were looked upon as an essential ingredient of all but the smallest circuses right from the early days. This stems partly from the historical association between circus and menagerie.

It is difficult to be precise when concerns were first raised about the role of wild animals in the circus, but perusal of books about the circus would seem to suggest that, at least as far back as the 1920s, there was an awareness of the issue.

As recently as the Victorian era, there was frequent staging of so-called “freak shows”, when people with unusual physical or mental traits were exhibited to the public as entertainment, but how much attitudes have changed over time.

The British public no longer finds it acceptable to have wild animals in a show whose function is primarily to provide entertainment.

Within the last decade, governments at Westminster and Holyrood have passed legislation which has ensured that the presence of wild animals in the circus is now effectively a thing of the past.

But it would be wrong to condemn the circus as it once was — what it offered was considered acceptable by the general public as it existed at the time. Pressure groups have undoubtedly played a significant part in mobilising and changing public opinion.

There seems little doubt that living conditions, and in particular, handling and training regimes, constituted a major consideration in the whole debate.

With many animals spending much of their time in confined conditions, and constantly on the move for long periods, it was a wholly unnatural existence.

At the same time, it has to be acknowledged that many circus owners felt a deep attachment to their animals. People like Thomas Ord and Bertram Mills were attracted to circus life first and foremost through their great love of horses.

George Sanger Coleman, grandson of Lord George Sanger, wrote: “My grandfather was utterly fearless with all animals. He was an expert and kindly trainer, with uncanny knowledge of any animal’s reaction.”

Writing in the early 1930s, Edward Seago stated: “Much has been written and said regarding treatment of animals in the circus. I knew personally many well-known trainers, and I can say with every confidence that wild animals are not trained by cruelty.

“We hear stories, but it astounds me that anyone believes them. Circus animals are not ill-treated, and in fact it is the reverse.”

Lady Eleanor Smith wrote in 1948: “In my experience, animals are trained by bribery: a piece of meat for lions, a carrot for a liberty horse, fish for the sea-lions.

“These, combined with extraordinary patience, achieve results that could never be obtained by whips and sticks.

“I myself am passionately fond of animals. Recently, the Circus Proprietors Association has refused to accept any animal act without a certificate from its own vet.”

But concerns over training and handling regimes refused to go away, and the trial of Bobby Roberts in 2012 may be revealing.

He was put on trial at Northampton Crown Court on three counts of cruelty to Anne, a 58-year-old Asian elephant (pictured right at Cardross), while at her winter quarters the previous year.

Secret filming by a pressure group showed a Romanian groom repeatedly kicking and beating Anne with a pitchfork. She was chained, and she was stated to be suffering from arthritis.

Roberts, 69, who was stated to have had health issues at the time of the filming, was found guilty, but the judge acknowledged that he was not directly responsible for the acts themselves, and that his own record was exemplary.

Further, it was recognised that his circus business was effectively at an end. However, he had to take ultimate responsibility for what took place in his name. With those considerations in mind, Roberts was given a conditional discharge, with no costs awarded against him.

Although circus owners might well be devoted to their animals, the same might not perhaps be said of some of those working under them. Bobby Roberts wife, Moira, said: “Bobby and I lived and breathed elephants.”

Many animals represented a large capital investment for the owners — as far back as the time of Lord George Sanger, a good elephant could be worth over £1000.

On the other hand, secret filming at one major circus showed the proprietrix ill-treating a chimpanzee, so owners were evidently not always beyond reproach.

The life of the circus goes on, albeit now in a format acceptable to the public of the 21st century. Although the circus no longer comes to Helensburgh, performances are staged from time to time at venues like Lomond Shores.

Many members of the old circus families are still in the business. In the case of the Roberts family, although the family circus has gone, one member went to Zippo’s circus, while another took up a position with Circus Sallai. The show goes on!