ONCE upon a time there was a vibrant hamlet — now Glenmallan on Loch Longside is the scene of a massive civil engineering project, using giant cranes.

The £63 million scheme is to rebuild Glenmallan Jetty, built in the early 1960s to service the Royal Naval Armament Depot at nearby Glen Douglas, so it is fit for use by the largest ships in the Royal Navy today to load and unload ammunition.

A passer-by would find it difficult to visualise the site as one which formerly hosted a small community, including for some years a well-loved school.

A passer-by would find it difficult to visualise the site as one which formerly hosted a small community, including for some years a well-loved school.

Local historian and Helensburgh Heritage Trust director Alistair McIntyre, who grew up there, says that people first put down roots in the Glenmallan area many centuries ago.

Up on the hillside was a farming settlement known as Stronmallanach. Records prove its presence as far back as the 16th century, but its origins could well be older, possibly much older.

It was abandoned in the mid 19th century, and today there are only crumbling drystone walls to tell of its presence, lost in a tumbled forest of Sitka spruce.

Stronmallanach was probably a casualty of moving to larger farming units at the time of its demise, with another factor being the lack of access to the public road along the lochside.

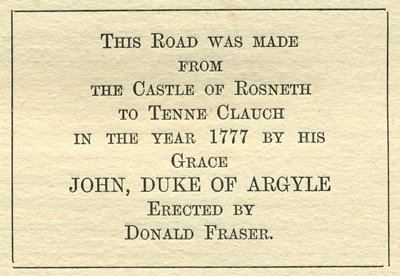

The road was built in 1777 — some accounts give the date as 1787 — by John, Duke of Argyll, to link his castle and estate at Rosneath with the existing military road from Dumbarton to Inveraray beside Loch Lomond and the Rest and Be Thankful.

A message was carved on a stone set into the roadside wall at the foot of Finnart Hill — Tenne Claugh is a place at Arrochar. The Donald Fraser who erected it was a farmer at Finnart.

Some sources give the date on the stone as 1787, but it is more likely to be 1777. The stone was refurbished in the 1950s by Australian Donald Fraser, a descendant of the Donald.

After the road was built, people began to settle at suitable places along the way, and one location was a small area of flat land near the mouth of the Mallan Burn.

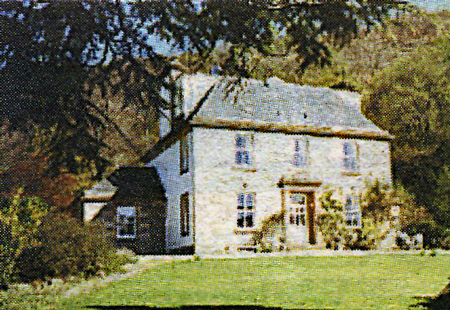

One of the first recorded houses to be built in the vicinity was Glenmallan House, constructed in the 1820s for John Colquhoun, who was the Sheriff of Dunbartonshire.

Lying close to the Mallan Burn on the south side, the site is very secluded, and few passers-by have ever seen it. More prominent is the lodge house, which stands next to the road.

An unusual facet of the Sheriff’s time there was an account he wrote of his experience when at home of the great Comrie earthquake of 1842, as reported in the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal of that year.

A later owner was a Miss Drummond, an admiral’s daughter, and her gardener was Peter McGregor, a descendant of the last farmer at Stronmallanach.

In the 1960s and 70s, an animal hotel was run from the house by Roy and Elizabeth Hart.

The house and lodge were inhabited until later that century, but they have lain empty ever since. The house, and others in the hamlet, tend to use the spelling ‘mallon’, but for consistency in this article I have used ‘mallan’.

Another early house nearby was Strone Tollhouse, located several hundred yards north of Glenmallan House and the hamlet’s most northerly dwelling.

It can be dated precisely to 1829, when it replaced the earlier Morlaggan Tollhouse, built as one of a string of tollhouses on the Dumbarton to Arrochar road after 1807.

Typical of tollhouses, it was built almost next to the road, while at the back it was hard against the steep hillside.

The toll-keeper was appointed on a year-to-year basis, the mechanism being to bid for the right to operate a given toll, a process conducted at the Elephant Inn in Dumbarton.

Bidding was often quite competitive, but at Glenmallan this seems not to have been the case, and Mrs Elizabeth McLellan, a widow, was in post from about 1850 until the national abolition of tolls in 1883.

She lived at the tiny tollhouse with her nephew, Peter, a wood cutter.

The annual rental paid by Mrs McLellan and her predecessors was usually £20, but this fell to £10 after 1853 and the passage into law of the so-called Forbes-McKenzie Act of that year.

This saw tollkeepers lose the right to sell alcoholic drink. Most toll rentals were affected in a similar way.

After the national abolition of tolls in 1883, some tollhouses were sold off, but many were retained by the road trusts, and from 1889, their successors, the county councils.

Strone Tollhouse (right) was retained by Dumbarton County Council, and it served mostly as a tied roadman’s house. As such, though substantially enlarged from the original, it ultimately formed a dwelling-house for John McGlone and his family from the 1920s onwards.

No narrative about Glenmallan can fail to mention the McGlones, and it is mainly thanks to Stella Trainor, a descendant who lives in Canada, that much of the wider story of Glenmallan has come to light.

John McGlone’s father, also John, had first settled at Thorniebank, a small cottage a couple of miles north of Glenmallan, around 1905.

He was not the first of the family to come to the area, however, and Suzy Reid of Suzy’s Castle fame had moved into her unique upturned boat home at Portincaple in the 1880s.

The Old Tollhouse fell empty in 1954, when the John and his family moved along the road to a newly built bungalow, more or less on the site of the former school, a little to the north of the Mallan Burn.

Not far from the Old Tollhouse was Strone Cottage (right), probably built in the mid 19th century to replace several old drystone and thatched homes located close by.

Owned by Luss Estates, at first it housed agricultural workers, but later saw a variety of tenants. One was George Dalziel, remembered as something of an eccentric. A keen astronomer, he lived in the house from the late 1920s until about 1950.

After that, it became a home for Nessie McGlone and her daughter for roughly a decade. They were the last occupants.

Along with the Old Tollhouse, the properties were demolished in the early 1960s, when Glenmallan Jetty and the private Ministry of Defence road to Glen Douglas were being built.

South of Strone Cottage was Stronmallan (left), a substantial half-timbered house built around 1880.

The exterior timbering was painted bright red, contrasting well with the whitewashed walls, and the property was popularly known as the ‘Lipstick House’.

For many years it was the home of the Rae family, whose interests included running the Whistlefield Tearooms, opposite the Inn Buildings.

The most prominent member of the family was Jessie Ronald, now Jessie Nickel, who under the stage-name of Glenda Mallon, became a notable singer and musician, studying in London and on the Continent.

Jessie now lives with her husband at St Albans.

The Rae family had a caravan in their grounds, and in the 1950s and 60s, this was rented by Miss Knox and Miss Henderson, both teachers at Hermitage School.

Miss Knox taught music, and Jessie has fond memories of her. They kept in touch until Miss Knox passed away.

A little to the south of Stronmallan was an originally wooden bungalow, owned by a Glasgow family, but rebuilt as a stone-faced bungalow in the 1970s. Jessie remembers Miss Donald, the owner, as “very prim and proper”.

It then became the home of a gentleman with two large dogs, who walked them very early in the morning.

He acted as an alarm clock for Jessie on Sunday mornings, when she needed to rise early, as she was organist at Garelochhead Church from the age of 14.

One method used to wake her was to throw stones at her bedroom window.

Next to the bungalow, on the south side, was Glenmallan School, built around 1929, when it replaced the school of 1926, originally conducted from one of the cottages.

The new school was a wooden building, and was in use until around 1947, when it closed at the same time as several others, including the one in Glen Fruin.

The new roadman’s cottage was built in the grounds. Between this site and the burn was a small area known locally as the Donkey’s Field.

A planned development in 1980 that never came about was the construction of ten holiday chalets.

One of the factors which may have gone against it was the proximity to the RNAD jetty.

Military planners were concerned about the potential dangers posed to civilians living close to such a facility, and this almost certainly is what led ultimately to the demise of the whole hamlet around 2,000.

Alexander’s Bluebird Buses once ran along Loch Longside, and there was sufficient roadside space at Glenmallan to allow them to halt there.

A large concrete ramp still exists for launching boats — Glenmallan is one of the few places along the lochside boasting anything resembling a beach.

Another Glenmallan feature was its role as a communications hub, as it had its own red telephone box. This survived the demolition of the houses, although it has since been removed.

Today, apart from memories, only Glenmallan House (left in its heydey), currently empty and in need of repair (below right), and Lodge remain as visible reminders of what once was there.

The farming settlement of Stronmallanach on the hillside above Glenmallan is long gone, but people who lived there are still remembered.

The settlement dates from the 1590s and ceased to be inhabited in the 1860s after the death of the only remaining occupant, retired farmer John McLean, who was in his mid-eighties.

In the 1970s the hillside around the settlement was planted with conifers, and this century several big storms toppled many of the trees, causing substantial damage to the remains of the two farm buildings.

Its hillside location brought advantages, including easy access to open areas of land suitable for cultivation, good drainage from the generally sloping ground, and the warmth afforded by a setting which faced to the south and west.

The two sets of buildings were almost certainly farms — and the Census of 1841 refers to two farmers. It seems reasonable to suppose they worked in co-operation, perhaps as a joint tenancy.

While records go back to the late 16th century, there is the suspicion that the site could go further back in time.

While the present ruins are in stone, it is likely that the original buildings would have been built of turf, in common with many of these old settlements.

One puzzle concerns the water supply. With both sets of buildings on the main ridge, there is no stream nearby, so where did the supply come from? Were there wells?

Quite possibly the only hope of providing answers to these questions would stem from archaeological investigation.

The demise of the settlement was probably inevitable, if only because it was well removed from the lochside highway, from which it is a steep climb.

However, Stronmallanach was not quite as cut-off as it might seem, as an 1860 map shows clearly a roadway or track from the site extending up through Glen Mallan to Glen Douglas, where it joins the east-west route through the glen.

The difficulties of transporting building materials to the site for upgrade to a modern, mortar-built farmhouse, would have been significant, so in a sense, the surprise is that the settlement survived as long as it did.

A Luss Estates survey from 1776 shows that even by that date, much of the ground comprising Stronmallanach was already being used for grazing sheep — at best some 43 acres would have been available for other agricultural use.

The Census of 1841 shows that four households down by the highway had between them nine agricultural workers present, over and above those actually residing at the two farms.

Sheep farming was not labour intensive. There would have been a need for more hands where arable farming was being pursued, but it is still hard to see how so many could have been utilised at Stronmallanach.

Some might have found work at neighbouring farms, but even so, there would have been limits. Perhaps some people eked a living from agriculture mixed in with other work, e.g. fishing, forestry and road maintenance.

By the time of the 1861 Census, though, the total of agricultural workers in the same locality was down to two.

By the turn of the 20th century, the whole of the hill extending from Stronmallanach to Glen Douglas was being run as part of one sheep farm, which also extended to the west flank of the hill to the east, Cruach an-t Sithean, all worked by one farmer and two shepherds, based at Craggan, beside the Glen Douglas road end.

A family grave at Faslane Cemetery, has a headstone which tells of a Stronemallanoch family. Behind the names are many stories.

It reads: “Here lyes the remains of Ann Campbell, spouse of Duncan McGregor, tacksman (rental farmer) of Strone Mallanoch, died 2nd March 1776, aged 30 years.

“This stone erected by Peter McGregor, gardener, Glenmallan, to the memory of his father, Peter McGregor, farmer Stronemallanoch died 22nd September 1847 aged 76 years, his spouse Mary McLean died 23rd February 1852 aged 72 years, their son Duncan, late manager of La Bonne Intention Estate, Demerara, died July 1844 aged 33 years.

“Their daughter Zillah died 28th February 1850 aged 37 years.

“Their grandchildren, son and daughter of Peter McGregor, Glenmallan. Catherine, died 29th July 1862 aged 5½ years. Peter, died 5th August 1862 aged 7½ years.

“Peter McGregor, Glenmallan, died 24th June 1895 aged 75 years. Also his wife, Elizabeth Rue, died 16th May 1908 aged 88 years.”

Peter Jnr., the gardener, was based at Glenmallan House, a large 19th century villa near Glenmallan bridge, where he worked for Miss Drummond, daughter of an Admiral.

Today it is owned by the Ministry of Defence, but it has lain empty for years.

There were other McGregors living at Stronmallanach at this period, and they may well have been related.

One of the couples, Gregor McGregor and Mary McDougall, moved from Stronmallanach to Stuckiedow in Glen Fruin not long before Ann Campbell’s death, and they had several children while living there.

Peter Snr. appears to have been quite a colourful personality. It is clear from the Old Parish Registers that he incurred the annoyance of the minister at Row, now Rhu, for not reporting the births of Zillah (1813), John (1816) and Peter (1819) until long after the events.

As well as running the farm, he also operated an illicit still.

An anonymous article published in the Lennox Herald newspaper of November 11 1899 states: “When Arrochar House was an inn, the proprietor was in the habit of taking an occasional keg from the grandfather of the writer.

“Sometimes the clergy had some sympathy with the illicit operations. On one occasion, the revenue officers had mustered at Arrochar with the intention of making an elaborate search.

“Mr Proudfoot, the minister at Arrochar, had wind of this plan. Knowing that Peter McGregor at Glenmallan had a sma’ still there, he sent his servant girl down the road to give warning that the rangers were coming.

“When the rangers got that length, they found nothing. That servant girl was the respondent’s wife’s mother.

“One night, Peter McGregor went along to Murligan for a jar at a ‘kirstin’ (christening). On his way home in the early morning, he heard a mavis singing.

“The bird sang in Gaelic, but in English its message was ‘Take a taste Peter, take a taste Peter’. So Peter took a taste out of the jar.

“Again and again, the bird’s song had the same tale, on which he again acted.

“Only on reaching home did he discover that the stick on his shoulder now supported only the handle of a jar!”

Peter Proudfoot was the local minister from 1817-43. It is possible that people like him might have had some sympathy with the illegal distillers, as a means of supplementing their meagre incomes.

Peter McGregor Jnr., the gardener at Glenmallan House, was highly regarded in the community, and in the Ordnance Survey Name Book of 1860, he is mentioned in a number of places as one of the authorities consulted on local place names.

He also made his mark in an unexpected way when he caught a record-breaking skate in Loch Long in 1851. Its length was 9 ft 2 inches, breadth 7 ft 1 inch, and weight 220 lbs.

The giant fish was described as the largest skate ever caught in Loch Long, and indeed in any of the sea-lochs within the Kyles of Bute area.

The McGregor family made their mark in various ways, but the younger generation did not see their future at Stronmallanach Farm.

This was an era of agricultural change, with consolidation of holdings into increasingly large farms, so they may have had little choice in the matter.

- The top picture shows the hamlet of Glenmallan; image, date unknown, from the Stella Trainor collection. Above left is the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal at Glenmallan for the final time in 2010. Photo by Fiona Holland. Below it is a 1927 image of Strone Tollhouse. The children are those of roadman John McGlone and wife Stella. From left: Agnes (Nessie), b.1920; John b.1922; Daphne, b.1923; Eileen b.1918.The 1895 image of Strone Cottage was taken by Professor Steggall. The girl in the straw hat is his daughter Frances. Below it is a 1903 image of Stronmallan.