IT IS amazing what can sometimes be found in an old book . . . but all is not always what it seems.

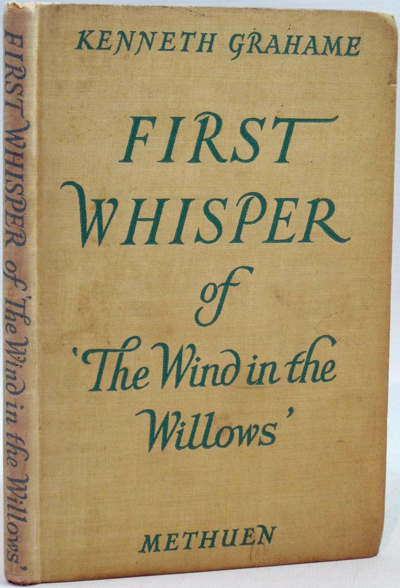

Former Helensburgh Advertiser editor, Fiona Howard, found a book “First Whisper of the Wind in the Willows”, by Kenneth Grahame, in the town’s Oxfam shop.

The book was first owned in 1944 by Margaret S.McLusky, of 38 South King Street Helensburgh, and inside it was a cutting of an article “Timeless voice of ‘The Wind in the Willows’,” by Agatha Henderson-Howat — herself a writer of stories for children.

In the article she mentions the Cunningham Grahame family, which might suggest a connection to the Ardoch-based family which included former Lord Lieutenant of Dunbartonshire Admiral Sir Angus Cunninghame Graham, and further back Robert B.Cunninghame Graham, known as Don Roberto, the adventurer, politician, explorer, and writer.

But there is an ‘e’ of a difference — and an Argyll connection.

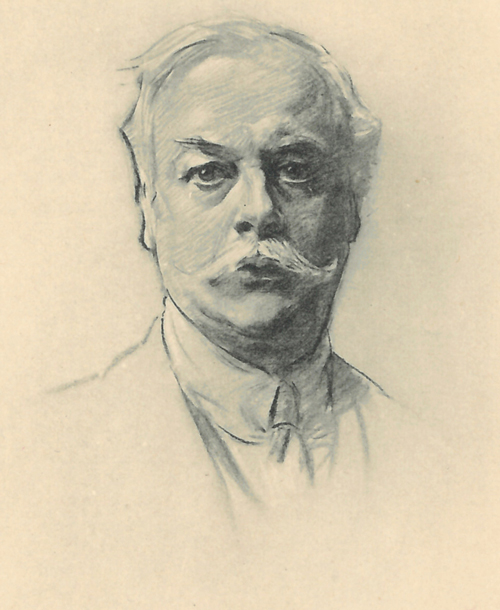

The author of childrens classic “Wind in the Willows” was Kenneth Cunningham Grahame (right), son of advocate James Cunningham Grahame and his wife Elizabeth Ingles, who was born at 32 Castle Street, Edinburgh, on March 8 1859 and died on July 6 1932 in Pangbourne, Berkshire.

Kenneth spent some of the first five years of his life with his family in the Inveraray area.

The article reads . . .

The Rat pushed the paper away from him wearily, but the discreet Mole took occasion to leave the room, and when he peeped in again sometime later, the Rat was absorbed and deaf to the world; alternately scribbling and sucking the top of his pencil. It is true that he sucked a good deal more than he scribbled; but it was joy to the Mole to know that the cure had at least begun.

It was to Cookham Dene that Kenneth Grahame returned to spend hours by the riverbank watching water-rats, moles, and toads going about their business. It was here that he wrote the book which was to be printed in more than 100 editions, and the Rat fretting and scribbling was the restless migrant in Grahame himself.

In the autumn of 1907 Grahame came most weekends to Cookham: it was a part of the Thames which had strong emotional associations for him.

Here he had been sent from Scotland after his mother’s death, and here the little family had tried to regain a sense of security in their grandmother’s house, “The Mount’.

It is against the uncertainty of his boyhood that we can best understand the man who wrote of the homes of the River Bank:

When the door had closed on the last of them and the clink of the lanterns had died away, Mole and Rat kicked the fire up, drew their chairs in, brewed themselves a last nightcap of mulled ale, and discussed the events of the long day . . .

The Cunningham Grahames’ third child was born in their gracious town house at 32 Castle Street, Edinburgh. Dr James Simpson, the Professor of Midwifery who was popularising the anesthetic value of chloroform, attended the birth of Kenneth.

His parents’ early married life was gay and happy. They entertained well as suited a popular advocate in the society of the New Town.

But the following year, 1860, James Cunningham Grahame was appointed Sheriff Substitute of Argyll, and the children began their series of moves.

In “The Wind in the Willows”, Kenneth — the child in strange surroundings — writes of early fears:

A child that has fallen happily asleep in its nurse’s arms, and wakes to find itself alone, and laid in a strange place, and searches corners and cupboards, and runs from room to room, despair growing silently in its heart . . .

But these were happy years and here the child found whatever afterwards he would search for — tranquility. Here Kenneth — already growing apart from his brother and sister — wandered along the beach where “the big blacksided fishing boats” lay or watched the paddle-steamers bringing in their strange cargoes and their whispers of an outer world.

So it came about that years later children read of the Rat torn with the tempest of conflict and the urge to roam the world, while the practical Mole was conscious always of the value of domestic and public virtues.

Here, so often, Kenneth himself stood at the parting of the ways — torn between what was and what might have been.

This is the timeless voice of “The Wind in the Willows.” Hidden or half-expressed longings are impersonated in the Toad, and the Badger, the Rat, and the Mole.

Stories Kenneth told to his own boy Alastair have charmed the children of 60 years, and they have brought wistful memories to the fathers who read them.

When Kenneth was only five his mother died of scarlet fever following childbirth, and he caught it too and was only barely nursed back to life. Her gaiety was dominant in her last words, “It’s all been so lovely.”

Kenneth was not strong after this attack, and although not consumptive he was, all his life, vulnerable to change of climate. He loved sunlight, good food, and wine. Mediterranean landscapes, the small intricate life of field and hedgerow.

James Cunningham Grahame was completely broken by his wife’s death. He turned to his consoler, Claret, and saw in his children an intolerable reminder of what he had lost.

Emotionally immature, intelligent but weak-willed, he remained in the granite house alone, and sent his family to their maternal grandmother at Cookham.

Mrs Ingles was not well-off, and little provision appears to have been made for the four children who had later to be helped by their uncles.

There is evidence of care, but little warmth in their upbringing. The loss of his mother at so early an age made a deep and lasting impression upon the boy, Kenneth.

At the beginning of “The Golden Age” he wrote:

Looking back to those days of old, and the gate shut to behind me, I can now see that to children with a proper equipment of parents these things would have worn a different aspect.

Once James Cunningham Grahame summoned his children to Inveraray. For a year in 1866 they stayed to make some show of social respectability, but for the sensitive Kenneth who went with high hopes and gay excitement, ‘‘Return, indeed, was bitter”.

They witnessed their father’s moral and physical disintegration. Then, fearing that the bolt would soon fall, the father resigned his post and went to scrape a bare living in France where he died alone 20 years later.

“Kenneth,” writes Peter Green in his biography, “could not rid himself of the vain dream with which he travelled north.” Much later he wrote of that journey to Scotland:

We are only the children who might have been . . . and for the sake of those dream journeys, the journeys that might have been. I still hear with a certain affection the call of the engine in the night.

The boy of eight felt sharply the sword between hope and reality. Now he would cling increasingly to the dream world where adults could not break, or torment, or kill.

And throughout the harsh facts of school life, the bitter enforcement of banking, the disillusionment of marriage, Kenneth (left, in his 20s) could escape into a world of serenity and gentleness, of laughter and home, the timelessness of things good and beautiful and true.

When the critics wrote coolly of the first appearance of “The Wind in the Willows” in October 1908, they did not realise, any more than did the publishers who turned it down, what a seller this book was to be.

Arnold Bennett alone, among much insensitive and barren criticism at least saw one aspect of the book: “The author may call his chief characters the Rat, the Mole, the Toad — they are human beings.”

But it was Richard Middleton In “Vanity Fair” who could write: “The book for me is notable for its intimate sympathy with Nature and for its delicate expression of emotions which I, probably in common with most people, had previously believed to be my exclusive property.

“When all is said the boastful, unstable Toad, the hospitable Water Rat, the shy, wise, childlike Badger, and the Mole with his pleasant habit of brave boyish impulse, are neither animals nor men, but are types of that deeper humanity which sways us all . . .”

It was an exceedingly difficult book to illustrate. The first edition carried only the frontispiece of Graham Robertson, “And A River went out of Eden.”

In 1930 Ernest Shepard was asked to make yet another set of illustrations for “The Wind in the Willows.” Grahame would have preferred the artist to be his friend Arthur Rackham, but the Methuen directors believed that Rackham would be too slow.

The Shepard edition was in fact on the market 10 years before Rackham, on an American publisher’s commission, completed eight coloured illustrations while returning to England from the United States on a voyage of the Queen Mary prolonged by the outbreak of war.

There are now five editions running concurrently. In spite of Grahame’s preference, and the undoubted artistic quality of Rackham’s pictures, it is Shepard’s conceptions of Toad, Mole, Badger, and the rest which have kindled the imaginations of generations of child lovers of “The Wind in the Willows”.

The ‘First Whispers’ book Fiona bought, published by Methuen in 1944, is a slim volume in two parts.

The first part is an introductory piece, possibly penned by Kenneth’s wife Elspeth. It is a homage to Grahame himself and a background to the publication of “The Wind in the Willows”, and includes interviews, reminiscences and anecdotes.

The second part consists of a series of letters that Kenneth wrote to his young son, in which he first sketches out his ideas for the adventures of Mr Toad. It condenses most of the book into a handful of pages.

Fiona said: “I bought it because ‘Wind in the Willows’ is an all-time favourite book of mine and it intrigued me. I find a lot of fascinating old books in the Helensburgh Oxfam shop — it is well worth a browse!”