A WELL-KNOWN face in Helensburgh and district was a man who saw a lot of the world, and more than likely his experiences helped shape a mature outlook on life . . . and his poetry.

James Hunter’s early years were inauspicious, as he was put to work at the age of nine. But his career then took him in a quite different direction.

He ran a successful bakery in the town centre for many years, and a number of his poems have a local setting.

Many details of his life have been shared by his great-grandson, Dr Bill Taylor of Welwyn, to whom credit is due for a good deal of what follows.

Born in the burgh of Rutherglen on New Year’s Day 1830, James Hunter was the eldest child of Hugh Hunter, a carter, and Marion Coats.

Marion had been in two previous relationships. Her first husband, David Gardner, a farmer, died relatively young, but not before she bore six children by him.

She then had two children by John Murdoch, another farmer, but the relationship was never formalised, and he subsequently sailed to the United States and abandoned them. So when James was born, he had a number of older half brothers and sisters.

Marion seems to have had a positive influence on the young James. A contemporary biographer wrote: “Like many another of the tuneful brotherhood, he was much indebted to his mother for natural and acquired gifts, as well as for the many graces which beautify his character.

“She was a woman of superior parts, kindly, sympathetic, and thoroughly imbued with love of country and her country’s songs.”

These influences spilled over into James, imbuing in him a sense of rhythm and appreciation of the art of putting words together, in poem and ballad.

Little has come to light about James’s formal education, although a newspaper article of 1884 refers to his mother as his sole educator. What is clear is that when he was nine he was put to work as a calico printer’s ‘tearer’.

The term conjures up visions of something destructive, or perhaps a need to rush from one work-station to another, but a tearer, or teerer, usually a young lad, assisted the printer by spreading a fresh coat of colour over the sieve or pad of woollen cloth on which the printer pressed his block.

James is next heard of as a baker’s apprentice, and he then obtained posts on steamers and transatlantic vessels. In one source he is referred to as a “seaman”, but almost certainly he was employed as a ship’s baker — a vital function.

He then spent some time in the U.S. and Canada, where several of his half-brothers had emigrated. It is known that he kept in touch with a few of them.

By 1857, James was living in Hutchesontown in Glasgow — and by now he had a sweetheart, Agnes Stewart, whom he married later that year. She was the youngest of seven children born to John Stewart, a seaman, and Agnes McKellar.

Many years later, she confided to William Jones-Hunt that their romance had blossomed at Faslane Bridge, about which Jones-Hunt had earlier written a poem, so they already knew the area.

James and Agnes had six children. James, the eldest, was born in Glasgow in 1859, but died in infancy. A later child was also named James. Agnes, the next child, was born in Helensburgh in 1861.

The census of that year lists the family as living at Alma Place.

A couple of years later saw them at Cupar in Fife, but by 1865 they had returned to Helensburgh and by 1871, if not before, they had moved ‘up the hill’ to 93 Sinclair Street.

James was employed in a bakery at 69 East Princes Street — before the east-west division in the town changed from Colquhoun Street to Sinclair Street in the 1890s. Many town addresses before that date do not correspond to those found from near the turn of the century onwards.

In 1865 James became a business proprietor in his own right, taking over a commercial bakery at the corner of East Princes Street and Sinclair Street, a prime site, quite possibly reflecting James’s acumen and ambition.

The census of 1871 describes him as ‘master baker, employing one man and two boys’. All this, along with the change of home address, reinforces the image of a self-made man.

He continued to run the bakery until 1877, when he moved to premises at 15 Dundas Street, Glasgow, a strategic city centre site close to Queen Street Station.

The Helensburgh business was taken over by Andrew Neilson, another baker, who in turn sold out to David S.MacLachlan, baker, around 1900. Today, the premises are occupied by Helensburgh Eyecare.

One of the features of running a traditional bakery is the necessity to stoke up the ovens very early in the morning.

William, the youngest child of James and Agnes, and the successor to him at Dundas Street, later recalled getting up at 4am to start work, the aim being to have fresh products ready in time for those travelling to and from Queen Street Station.

If not initially, the business came to include not only a bakery, but a confectioner’s and a tearoom.

A totally unexpected development took place in 1880, when James successfully bid to operate the toll-bar at what was then spelt Ardincaple. The successful offer was £766, a lot of money at the time, and a further indication that James was doing well.

As the Dundas Street business continued to operate, and as William was still a child aged 11, there must have been a reliable manager or manageress in post. None of the other children was destined for a career in the business.

The census of 1881 reveals James (50) and Agnes (49) to be living in the tollhouse, along with five of their children, of whom two were now working.

Bill Taylor, William’s grandson, suggests the move may well imply that James was now a ‘gentleman baker’, and that his aim could have been to scout out a possible future home in the area.

Whatever the motivation, the family were at the tollhouse for only one year. The toll was let to another bidder the following year, but for the same amount as bid by James the year before.

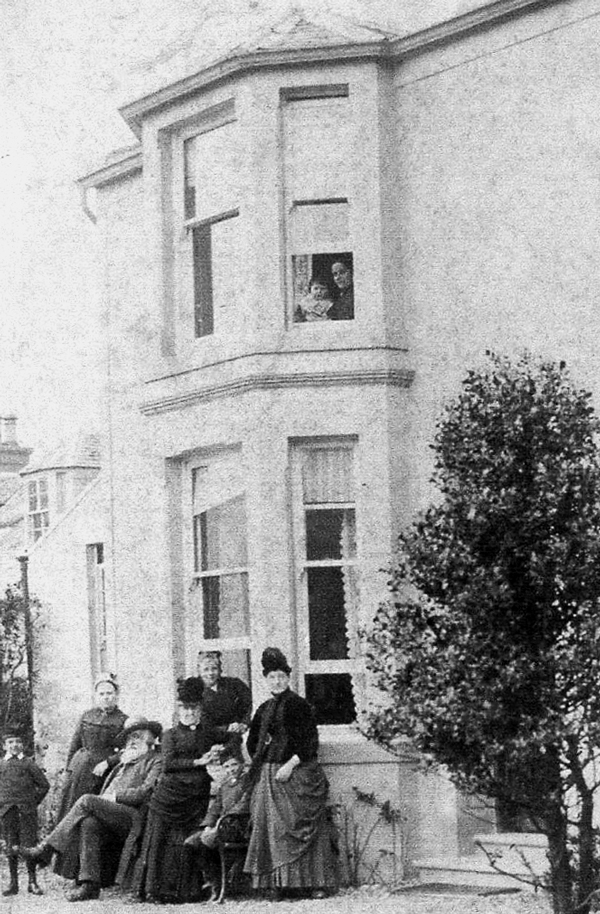

In 1884, James purchased Caerphilly, a gracious villa overlooking the Gareloch at Garelochhead, and this was the family home until 1896.

He also had a residence in Glasgow at Holmhead Street, now Cunningham Street, not far from the Dundas Street business, and he was there with family at the census of 1891.

Caerphilly was leased to Mrs Saunders in 1896 with an option to purchase for £700, which she did in 1902, following the death of James in October 1898. The Dundas Street business was continued by son William until his retirement in 1930.

It is not known when James began to compose poetry, but many of his poems are set in and around Helensburgh. He must certainly have been active well before 1884, because a small publication appeared that year, entitled “Poems and Sketches”, by James Hunter.

A review appeared in the North British Mail newspaper of July 21 1884, and the reviewer stated:

“Poems and Sketches”, by James Hunter (Glasgow, William M.Stuart) is an unpretentious little volume by one whose “reluctant assent” to the requests of friends wishing to have his poetic productions in print, strikes us as more genuine than such phrases in a preface often are.

Local characters and scenery in Helensburgh and along the shores of the Gareloch are the themes of most of the pieces, and on nearly every page there is a touch of nature, while the sincerity of the writer’s motives is obvious throughout.

One piece commemorates a local worthy, “Jeems”, who:

“Was baith police and fiscal,

Focht his way up in by inch,

His very word fired like a pistol,

Jeems was maist as high as the bench...

The bailies a’ grew jealous,

And sent him doon tae man the pier...”

“Willie Gray the railway guard” is the subject of a warm eulogium. Mr Hunter would seem to be an eclectic in politics, for while on one page he upholds the bold “Ferniegair” as the unflinching champion on the School Board of “use and wont”, in more than one piece he subjects the Jingos to trenchant criticism:

“Who prays now for peace and all such humbug, Should be nailed like a slave to a post by the lug. Now the war fever rages- they’re ready to kill, Shuest them on Dizzy. By Jingo, I will!...” (“Dizzy” is a reference to Disraeli)

Not the least effective piece is a castigation of the Rev Mr McCrie of Ayr for his “defamation” of Burns, and there is a happy denunciation of the new promenade at Helensburgh:

“Saut-water folks fae Glasgow toon,

What will they sat ava’

A muckle dyke before their nose.

Jist like the Broomielaw...”

Willie Gray was a real person. In 1865 he was living at 7 East Princes Street, and by 1875 at 15 Lomond Street. His widow continued to live there, the last entry in local directories being in 1901.

A Willie Gray, an engine driver, was living at another town address until 1919, and it could be that he was a relative.

Much of James’s poetic output does not feature in the book. Perhaps with increased leisure time in his later years, he had more time for writing.

In the 1890s he arranged a meeting at Caerphilly for some like-minded people.

His interest had been drawn to William Jones-Hunt through publication of several of the latter’s poems in the Helensburgh and Gareloch Times. One was “Faslane Bridge”.

Jones-Hunt was a native of the Bristol area, but developed a love for the West of Scotland, and spent a number of holidays based in Helensburgh.

James invited Jones-Hunt to visit him at Caerphilly. In his letter, he gave a useful self-description, so that when Jones-Hunt disembarked from the steamer at Garelochhead, he could recognise him: “Well, I am six feet, stout built, white beard, grey suit, straw hat: you know the age.”

The gathering at the house included several other poets, including members of Glasgow Ballad Club which was founded by William Freeland in 1876.

James was a member or supporter, and he became acquainted with the others, including Donald McLeod, a well-known author of books set in Dumbartonshire, and described as “a hatter in Dumbarton, and a baillie there”.

Another was John Butt MacLachlan, who would go on to serve as town clerk of Helensburgh for many years, having served jointly in that capacity with his father, George MacLachlan, for quite some time before that.

A non-local was David Wingate, known as the “Colliery Poet”, whose second wife, Margaret Thompson, was a grand-daughter of Robert Burns.

He was undoubtedly a more significant poet than the others, and a collection of poems published on behalf of Glasgow Ballad Club contains a good number of his works.

James’s affinity with the Ballad Club genre led him to compose several ballads. One was called “Tam’s Doug” — Tam was a well-known Helensburgh personality, and his faithful canine companion was equally familiar to town residents.

Almost any topic could motivate him to set down something appropriate in verse, such as the imposing-sounding “To the First Dumbartonshire Volunteer Artillery”.

The unit was part of a national initiative launched in 1860, over fears of growing French military power and ambitions, and soon two volunteer companies were set up in Helensburgh, one for artillery, one for infantry.

James Hunter may never have been a poet of the first rank, but as the North British News rightly observed, his work was always sincere, and sometimes tinged with good humour.