NUMEROUS poems have been composed about Cardross and its surroundings, including several by poetesses with village connections.

The best known was Frances Porter Stoddard, who was born in New York in 1843 to American parents whose roots in the New World went back to Puritanical settlers who arrived in 1639.

Her parents held strong beliefs, among them a passionate opposition to slavery, and such attitudes had a profound effect on young Frances.

Her father, Arthur Francis Stoddard, was a successful businessman who was a merchant in silk products, but after a slump in the domestic market, he moved with his family to Scotland in 1844.

The family’s opposition to slavery may well have played a part in their decision to emigrate.

However, after setting up home in the Glasgow area, Stoddard found that many influential people there were supportive of slavery, if only out of self-interest, something that came to a head at the time of the American Civil War.

As an outspoken critic, he made some powerful enemies. At the same time, he was a sophisticated cosmopolitan businessman, having earlier worked for some time in London.

He took over a failing company manufacturing tapestry carpets, whose fortunes he was able to turn round, thanks to his network of overseas business contacts.

This was to become the world-famous Stoddard Carpets, wound up as recently as 2005. When Arthur died in 1882, he left £325,000 — about £4.5 million today — so the family were well-off by any standards.

The Stoddard family lived for some years at Thornhill House, Elderslie, but by the Census of 1871, they had moved to Broadfield House, Port Glasgow, a mansion on an elevated site just west of Finlaystone Estate, with splendid views across the Clyde.

Among family members listed there in the 1871 census was Frances (26), the eldest daughter. There were also three guests, among whom was a David Murray, described as a ‘Prosecutor’.

Murray, later Dr Murray, married Frances the following year, and is remembered today as a famous lawyer, antiquarian, author and bibliophile, their home being at Moore Park in Cardross.

The occasion seems to have been something of a matchmaking success — another of the guests married a younger sister of Frances soon after.

Frances was educated largely at home, though she did attend a finishing school in London. A lecturer in Scottish music and a writer, she believed strongly in female emancipation and the education of women, following in the footsteps of her parents.

A great lover of outdoor sports, a keen yachtswoman, horse rider and skater, she came to share her husband’s passion for archaeology and antiquities.

They enjoyed yachting holidays, taking every opportunity to visit interesting sites. One outcome was a privately printed book, entitled “Summer in the Hebrides: Sketches on Colonsay and Oronsay”.

She also took a keen interest in the life of Cardross, helping to organise a number of events, and giving talks on various subjects to large and appreciative audiences in Helensburgh and the village.

Frances and David had several children, including Sylvia Winthrop, Dorothy, Eunice Guthrie, and Anthony Stoddard. Eunice and Sylvia are pictured (left) int he garden of Moore Park

Sylvia was an authoress and personality in her own right, but Eunice is the best remembered of that generation, and she carried forward the political torch once held by her mother and also composed some poems.

Anthony, the only son, served in the First World War as a 2nd Lieutenant, but was wounded and captured during fighting near St Quentin in 1918, his injuries quickly proving fatal.

Frances’s strongly held views on various political and moral issues feature in some of her poems, but the accent was very much on family life and the countryside.

This is perhaps not so surprising, as the motivation in writing poetry might well include setting aside the grimmer side of life. One poem is entitled “A Winter Ride at Cardross with my Daughter, Five Years Old”, and the opening verse runs:

“Mother said to Sylvia, “Little little lassie run!

Get the horses saddled, that will be such fun!

We will do a-riding, only you and I,

While the daylight lingers, fast away we’ll fly...”

There is a mood of excitement and anticipation in these simple words — it is a world of adventure and freedom from cares, with love of family centre stage.

Another noted Cardross poetess was Euphemia McArthur. Her parents both hailed from Islay, and her father was employed for many years by John McIntyre, wood merchant, at Geilston.

She had a connection with the Murray family, as for eleven years she was in service with Mrs Murray, the mother of Dr David Murray and the widow of David Murray, who, like his illustrious son and namesake, was a lawyer.

Euphemia’s poems are characterised by a deep love of Cardross, as viewed in exile, exemplified by “Lines to Cardross”, in which she recalls the happy times when she lived there. It begins:

“Sweet Cardross, village of the Clyde,

Thy green and grassy braes,

Are dear to me, and bring to mind,

The past long by-gone days...”

She contrasts the pastoral setting of the village with her present life in the city:

“Amid the city’s toiling throng, a dweller now am I,

Where high stone walls and louring smoke,

Blot out the hills and sky...”

Another poem in similar vein of honest sentimentality is a glowing celebration of Geilston Glen. It begins:

“O, dear to me is Geilston Glen, Each mossy bank and flowery den,

Each leafy tree, ah! Dear as when, I first saw Geilston Glen...

‘Tis there you hear the mavis sing, Whose mellow notes melodious ring,

All that is lovely seems to spring, Around fair Geilston Glen...

Sweet, cherished dreams around me flow, Of days and scenes of long ago,

Of kith and kindred lying low, Far, far, from Geilston Glen.”

With Cardross set in prime agricultural land, farms and farming life have long occupied a key place in the life and times of the community.

An agricultural society was an early village institution, and under its auspices, an annual ploughing match was held and keenly anticipated. The venue rotated each year among the different farms.

In 1869, one spectator wrote a poem about it. His name was Robert Lawson, and although little has come to light about him, he was evidently a local man and well acquainted with the different farms and those who worked them.

The poem, called “The Cardross Ploughing Match”, begins:

“Last Friday morn the Cardross lads they met to try their hand,

Down in a fine field of Craigend, in turning ow’r the land.

Fourteen ploughs came on the ground - their harness bright did shine -

The men and horses they were fresh, and started in good time.

Willie Traquair o’ Cairniedrouth made twa fine rigs they say,

And carried aff the foremost prize frae Cardross lads that day,

A smart wee lad is James Traquair, his wark he made it tell,

And carried aff the second prize - the Cairney lads did well...”

Various other farms and personalities are mentioned, and the poem concludes:

“Here’s tae the Cairneys and the Glens, the boys o’ Kilmahew,

And a’ the ither Cardross lads, lang may they haud the plough.”

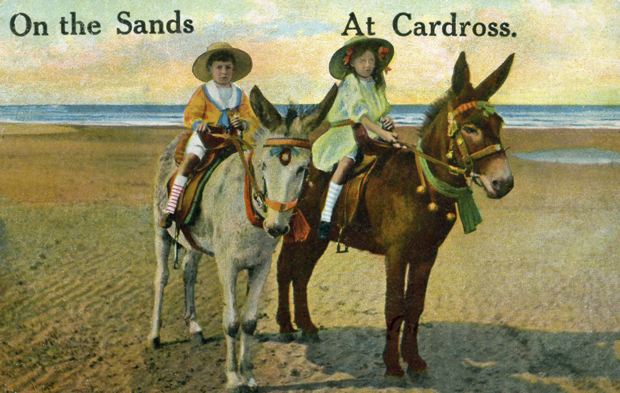

The shore at Cardross has always been a great attraction for local people as well as those from further afield — as this 1917 postcard illustrates — and it has attracted quite a few poems.

The shore at Cardross has always been a great attraction for local people as well as those from further afield — as this 1917 postcard illustrates — and it has attracted quite a few poems.

One time-honoured event which attracted verse was the village Wulk Fair. Its origins go back quite some way, but over time a dominating influence came to be that of Bonhill Fast Day, which took place on the Thursday before the Communion Sabbath, usually the one held at the end of April or beginning of May.

On that day, all the textiles factories in the Vale of Leven were closed, and many employees took the opportunity to make their way over to Cardross by Carman Hill or Stoneymullin.

As the name of the Fair suggests, shellfish, especially whelks, were at the centre of it, but there were many other attractions, including stalls of various kinds, all calculated to appeal to the visitor.

One person recalled: “Cardross Fair was associated with wading, inhaling the smell of the alleged sea, the eating of gingerbread cut from a block like bars of soap, the selecting of the crumpy sweets in the Scotch mixtures, and the licking and sucking of the pink-coloured and rose-flavoured sweetie hearts the size and weight of a girl’s peever.”

Cardross women were kept busy harvesting shellfish in good time for the big event, although some of those attending would have preferred to pick their own.

In its heyday, the Wulk Fair also offered donkey rides, swing boats, games, and booths with coconut shies, and no doubt Punch-and-Judy shows.

One of those who wrote a poem about the Fair was Humphrey Davie — not to be confused with his near namesake, the inventor of the miner’s safety lamp. Davie was the son of a farmer who had the tenancy of Maligs Farm, later engulfed in housing.

Born in 1848, Humphrey was brought up in Helensburgh and held various posts before becoming chief cashier with the Milton Ironworks in Glasgow. In due course, he took up residence at Geilston.

A biographer wrote: “Since moving to Cardross five years ago, Mr Davie has devoted himself to mainly literary pursuits. He is master of many moods, but it is considered that he is particularly strong as a raconteur.

“In social circles, Mr Davie is a genial good soul. He is also imbued with antiquarian, artistic and other tastes of an elevating nature.”

One of Davie’s poems is called “Cardross Whelk Fair”, and begins:

“Wife and weans, yer faces wash, Don yer claes fu’ hasty.

Owre tae Caurdross let us bash, On the shore tae draig glet dash,

Aff wi’ care! Awa wi’ sulks! Whit is’t is sae tasty,

As wulks an’ cockles, mussels, dulse?

Oh, mussels, cockles, dulse an’ wulks!...”

Another verse relates:

“Fires alang the shore we’ll hae, Tea and shellfish bilin’,

Owre tae Caurdross let us gae, Sookin’ sweeties - dancin’ tae -,

Clap the coo the lassie mulks, Wha is’t thinks o’ tilin,

Whaur’s wulks an’ cockles, mussels, dulse?

Oh! mussels, cockles, dulse an’ wulks!”

The poem concludes with the happy but tired return over Carman, set against the backdrop of the sun sinking down “Whaur a’ Cowal grandly bulks”.

The First World War and its aftermath had a bad effect on the Wulk Fair, though it may only have hastened the end.

The Fair did soldier manfully on into the early 1920s but its days were numbered. A later attempt to revive it failed.

Even so, the Cardross shore continued to attract many visitors wishing to enjoy the surroundings and the seaside fresh air, many arriving by train at the nearby station.

The attraction was so strong that some people erected a variety of temporary and even semi-permanent summer shelters along the shoreline.

The Helensburgh and Gareloch Times reported in July 1922: “The community starts at the west end of Cardross, where about thirty tents are pitched adjacent to the Burns Park.

“Opposite Cardross Station, animated scenes are witnessed daily between the campers and the day trippers; dozens of fires being kept going for cooking purposes.

“Here also are numerous stalls for providing refreshments in the form of ice-cream, aerated waters, confections, etc, all doing good business.

“Crossing Geilston Burn, the tents are more congested for about a mile along, all of various shapes and sizes, good, bad and indifferent, many neither wind nor watertight, composed principally of sacking, ground sheets, and any other like material.

“A favourite form is large tarpaulin, which provides a roomy, comfortable bivouac.

“The feature among this lot of temporary dwellings is the artistic taste developed, many of the occupants vying with one another in the decoration of ground surrounding their tents.

“The work is done in sand, shells and white pebbles, the name of the tent, or the nickname by which the occupants choose to be known, being neatly figured out and bordered.”

A poet who wrote of the continuing lure of Cardross shore was Andrew Stewart (left). Born in 1905, he was brought up in Alexandria by an aunt, Margaret Ross, whose maiden name was Stewart.

He did well at school, but family circumstances dictated that he entered the world of work on leaving, and he spent many years in local textiles works.

He later composed several poems which highlighted the harsh and unhealthy conditions for workers in those factories.

Andrew loved the social life, but it was not until 1940 that he married his sweetheart, Dumbarton girl Jessie Campbell. There was one child, a boy, but he died shortly after a difficult birth.

With the coming of Detroit-based Burroughs Adding Machines to the Vale of Leven around 1948, he became their photographer. At one stage, the firm employed around 2,000 people at Strathleven Industrial Estate.

Andrew had a talent for writing, and in addition to composing poetry, he was a frequent contributor of articles to the local press.

He worked for several years as an editorial assistant at the then Helensburgh Advertiser office in East King Street.

A very popular member of the department, he died on December 29 1995 at the age of 90.

One of Andrew’s poems, “The Jeely Eater’s Quiz”, was published in the County (now Dumbarton) Reporter newspaper in 1973, and it asks all sorts of questions about local haunts and personalities from his younger days.

One verse runs:

“Did you ever cross Carman, wae some pieces and a pan, or walk ower Staney Mullen to Ardmore?

Yet never seemed to tire, as you kenneled up a fire, and sampled Caurdross tea doon by the shore?”

Another poem, entitled “A Renton Reminiscence”, was written at the request of the Rev James Currie of Millburn Church, Alexandria, a much respected minister and after-dinner speaker, for use as a quiz.

It centres on an old man who takes his grandson on a walk and describes to him various episodes from his younger days. Happy days at Cardross shore are recalled:

“He spoke of the picnics at Cardross, and the walk o’er Carman coming back,

With his tea-pan hung from his shoulder, and a big bag o’ wulks upon his back...”

It would be interesting to know when such local rituals fell into disuse, but it might be that the Second World War would have seen them out.